What are concept or mind maps?

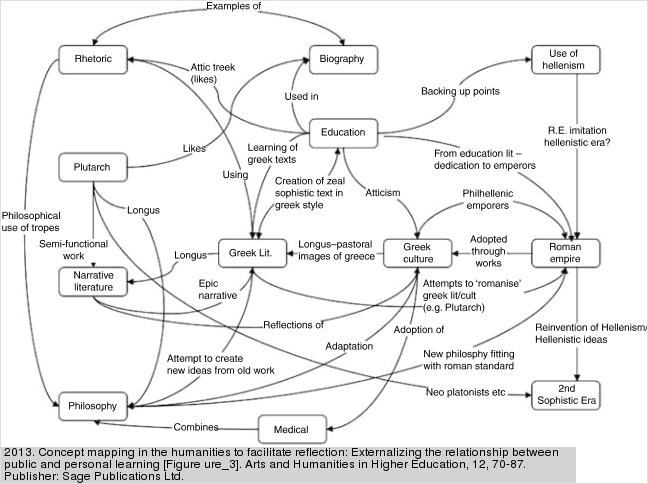

Concept or mind maps can help learners think through a question or topic by visualizing the relationships between concepts, arguments, evidence, and themes. Links between nodes show the connections between these ideas. In general, the term concept map describes hierarchical diagram building downward, connecting multiple ideas in a more formal way. Mind maps tend to focus on a single idea at the center, building outward in a creative way often using color or images. Your learning goals are more important than the formal distinctions between concept and mind maps, and it may be most natural for your students to combine aspects of both types of maps, as in the following example:

What are the benefits of small-group concept mapping?

Incorporating concept maps in the classroom can:

- Increase student engagement though active learning. Having students produce concept or mind maps in small groups offers more time for each student to grapple with and articulate key ideas.

- Improve student performance through collaborative learning, which studies consistently show to be more effective in producing learning outcomes than individual learning.

- Connect to diverse learning styles.

- Provide a low-stakes assessment of student learning.

- Offer students variation in students’ studying routines, which helps students move beyond memorization to deeper learning. Consider incorporating a concept mapping activity into a review session before an exam.

- Foster higher levels of learning in Bloom’s taxonomy. Beyond simply remembering facts, students must also analyze the relationships between ideas, justify their choice of connections between different nodes, and construct a visual representation of a topic.

Incorporating small-group concept mapping in class:

Explain the idea of a concept map and distribute an example map of a different topic in your discipline. Depending on your academic discipline and learning goals, you may instruct students to visually differentiate or label different types of nodes and connections. Give students a key question or problem as the focus for their diagrams. It might be a singular question that forms the central node of the diagram (what are the elements of…?), instructions to compare and contrast two concepts, or a question that puts a few key themes into conversation (what is the relationship between race, class, and gender in…?). If you choose, you can also give students a list of concepts or sources to include in their maps. Be transparent in your teaching: explain how the exercise relates to the course goals and what students should get out of it.

Divide students into small groups to begin mapping. Circulate around the room as students work on their concept maps, asking for the rationale behind their decisions and prompting them to consider new factors. Once students have produced their maps, use a document camera to project each group’s diagram. For the sake of time, you might ask each group to explain a particularly important or original portion of their work. These maps do not need to be treated as final products. Encourage students to offer suggestions or ask questions to improve other group’s maps. As the instructor, you might find it useful to draw changes on a map to explain a common misunderstanding that needs correction.

Leave enough time to debrief the exercise. Ask students to construct an answer to the initial question. Collecting a final map from each group will allow you to gauge student understanding. Just remember to make photocopies or post scans of all the groups’ work to Sakai so that students can refer to the material for future projects or studying.

Practical tips:

- Consider the physical constraints of your classroom. Will there be enough space for small groups to work around a sheet of paper? Do you have a document camera in the room to project each group’s work?

- Depending on your constraints and learning goals, you might do a variation of the above activity by having students begin individual maps before working collaboratively or working as a whole class using the whiteboard.

- What preparations are necessary? Will students need to have notes or texts from previous weeks at hand? Should they bring colored pens or pencils?

- Several online tools have been developed for concept mapping. See this list developed by our own Chris Clark.

Additional Sources:

John W. Budd, “Mind Maps as Classroom Exercises,” in The Journal of Economic Education, 35 (1), Winter 2004, pp. 35-46.

Michael Prince, “Does Active Learning Work? A Review of the Research,” in The Journal of Engineering Education, 93 (3), July 2004, pp. 223-231.