In our new Faculty Feature series, the Kaneb Center interviews teachers around campus to learn about what motivates them, discuss techniques they use in their classrooms, and share bits of wisdom with others in the Notre Dame community and beyond! Our first article features Patrick Clauss, Director of Writing and Rhetoric in the University Writing Program.

Tell us a little about yourself.

I’m a South Bend native, having grown up just a few miles off campus. My maternal grandfather, Dr. George Hennion, was the Julius Nieuwland Chair of Chemistry for much of his career at Notre Dame. To my grandfather’s great disappointment, I struggled in high school chemistry, finding that my interests and talents were in the liberal arts instead.

I joined the Notre Dame faculty in 2008. Previously, I taught at Butler University for eight years, where I also directed the writing center. Here, I am the Director of Writing and Rhetoric in the University Writing Program. In addition to teaching Multimedia Writing and Rhetoric to First Year students, I also mentor approximately 15 graduate student instructors each semester, doctoral candidates from across Arts & Letters who teach Writing and Rhetoric. In the spring of 2014, I was honored to be named a recipient of the Rev. Edmund P. Joyce, C.S.C. Award for Excellence in Undergraduate Teaching. This year, I am a Kaneb Center Faculty Fellow.

My research interests dovetail nicely with my teaching: My areas of interest include argumentation theory, rhetorical theory, and composition pedagogy. Essentially, I am interested in two related questions: What makes a natural-language argument (written, spoken, visual) true or valid, and what makes a natural-language argument persuasive? Validity, truth, and persuasiveness are not the same things of course, as anyone who’s followed recent political campaigns can certainly attest.

Why did you decide to become a teacher?

Originally, as an undergraduate at Indiana University, I set out to be a high school English and French teacher. However, while student teaching many years ago, I discovered two important things about myself: First, while I have great respect for high school teachers, I do not have the patience to deal with teenagers all day long. Second, I have an insatiable curiosity about argumentation, persuasion, and rhetoric. With just my bachelor’s degree, for instance, I felt as if I had barely scratched the surface of what there is to know about communication. Consequently, I returned to school, earning my master’s and then my doctorate in English, focusing on rhetoric and composition. While in graduate school, I taught a variety of writing and literature courses, and I soon fell in love with college teaching.

In what ways do you find teaching rewarding or meaningful?

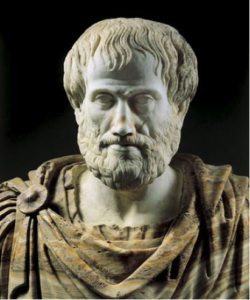

This is easy: I work with smart, talented students discussing topics that fascinate me: Aristotle’s On Rhetoric, inductive and deductive reasoning, rhetorical theory, and critical thinking, among other areas. Just last week, for instance, I discussed the Aristotelian virtues of good sense, good moral character, and goodwill with my Writing and Rhetoric students. I’ve taught that particular lesson numerous times, but as we watched various campaign ads together and considered their effectiveness using Aristotle’s framework, I did not want class to end. Seventy-five minutes fly by when you’re doing something you love. Plus, I take very seriously my responsibilities to educate  students in a democracy, where all citizens must make informed choices about a tremendous variety of issues.

students in a democracy, where all citizens must make informed choices about a tremendous variety of issues.

Describe one teaching technique you like to use in your classes.

As an undergraduate, I was in a French history class with at least 75 students. The professor asked each of us to write, in French, a one-page response to the prompt “Tell me about yourself.” Weeks later, when I stopped by his office with a question, he remembered several things about me, things I’d shared in the paper. I was quite impressed. He took the time to get to know each of his students, even in a large class at a Big Ten university. When I began teaching at the college level, I too began assigning such an assignment, one I still use to this day. In all of my undergraduate classes, the first writing assignment is pulled directly from Professor Berkvam’s playbook: “Tell me about yourself.” While reading this assignment, I get to know each student on a personal level. Among other things, this allows me, when possible, to tailor activities and assignments to my students’ interests.

What advice would you give to a new teacher?

If you think you are not reaching a particular student, that a particular student is “checked out,” be very skeptical of your abilities to make that judgment: Always assume the best about a student’s engagement, even when that student sits in the back of the room, rarely or never participates, and seems disconnected from the class. Definitely work to engage everyone in your class, but don’t dismiss or write off the student who doesn’t seem to care. So many times in my career, I have been contacted by just such a student long after my class has ended, months or even years later. I’ll get an email with something like the following, “You probably don’t remember me, but I was in your class a few years ago. The other night, I was watching the presidential debates, and something one of the candidates said reminded me of what you taught us about argument and persuasion . . .” It may not have seemed like it at the time, but I reached that student. I made a difference in that student’s life. Be eternally optimistic about all of the students in your class!

In your opinion, what makes a great teacher?

This is a difficult question, as there are so many great teachers with such different styles and approaches. I try not to take myself too seriously in the classroom, but I also try—even on days I’m tired or preoccupied with something else—to demonstrate that there is no better place to be than in a classroom at the University of Notre Dame. If I don’t care about the topic, lesson, or activity, how can I expect anyone else to care? I frequently ask students, “Isn’t this interesting?” or “This is fascinating, isn’t it?” That’s not pretense on my part. I really mean it.

Is there anything else you’d like to share?

Here’s a fun story from the first college class I ever taught, in the fall of 1990: I was a 23 year-old graduate student instructor, standing in the hallway waiting for the class before mine to dismiss from the classroom. One of my students, whom I had not yet met, leaned against the wall next to me. “Do you have English class next?” he asked me. Nervous about teaching, I didn’t think through my answer. “Yes, I do,” I told him. “Man, I hate English class” he replied. It occurred to me then that he thought I was a fellow student. “I hate it sometimes, too,” I jokingly said.

As the class before ours left and we walked in the classroom together, he sat in one of the student desks, looking at me to sit next to him. I continued to the front of the room. Setting my materials on the teacher’s desk, I watched a look of horror wash across his face as he realized I would be his teacher for the semester. For the rest of that first class, he hid behind his baseball cap, pulling it down as far as it would go.

When class was over, I took the student aside and thanked him for making my first day of college teaching memorable. I also assured him I would not hold his comment against him. (I did suggest he be careful, in the future, about assumptions about his audience, whether in writing or speaking situations.) Every semester since then, I still think of that young man on the first day of class. I’m still nervous on the first day of each semester, but that memory makes me smile every time.

Thanks, Patrick!