A post from our student blogger Sarah Goodman

The main type of intellectual property the MSPL courses focus on is patent law. The program prepares individuals to pass the patent bar and work as patent agents. A patent agent is qualified to prepare, file, and prosecute patent applications. Although a patent agent is not qualified to work in the other areas of intellectual property law, it is important to understand the other types of intellectual property rights that are used in science.

Copyrights protect original works of authorship for a limited time. Included are literary, dramatic, artistic, and musical works. A copyright generally gives the owner the rights of reproduction, distribution, and performance. A work must exist in a tangible form of expression in order to qualify for copyright protection. In science, copyrights are often used to protect literary works such as books, articles, and website content. Genomic DNA sequences are not generally considered to be covered by copyright because they are not works of authorship.

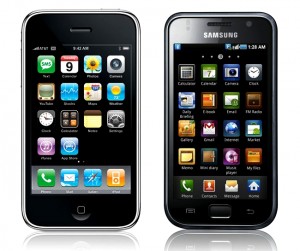

A trademark is a distinctive mark that identifies the source of a good or service. Examples include words, phrases, logos, symbols, and designs. A trademark provides recognition protection to the owner by granting the exclusive right to use the trademark to identify goods or services. Trademarks are commonly used in science to identify company products. When a product or service is labeled with a trademark, a consumer can quickly identify the source and expect consistency. Rights to a trademark are acquired by either being the first to publically use the mark in commerce or by being the first to register the mark with the USPTO.

Trade secrets give a company a competitive advantage by keeping information confidential. Trade secrets are information with commercial value and are subject to steps to ensure secrecy, such as through confidentiality agreements. Sometimes, if an invention is patentable, a company needs to decide whether to make their invention a trade secret or to submit a patent application. Benefits to trade secrets include an unlimited time frame (as long as undisclosed to the public) and no costs for patent registration and maintenance. The disadvantages include that another entity could patent the trade secret independently and the owner of the trade secret does not have the right to exclude others from using the secret. Also, once the trade secret is revealed, there is no intellectual property protection for the original owner.

Patents are extremely important for the stimulation of innovation in science and are the primary focus in the MSPL courses, but it is necessary to also be familiar with other types of intellectual property.