By: Emma Hokoda

Dripping in sweat and damp from the rain, I slid into my seat on the small Nigerian plane and took some deep breaths to let my racing heart slow down. A few short hours ago, I was shaken awake by my teammates and informed that our plans had changed, yet again. We rushed to the airport, bought our tickets, and narrowly made it to the plane on time.

My teammates Nancy Obonyo, Colleen Maher, and I have handled our fair share of logistical challenges over the course of our Integration Lab (i-Lab) project thus far. Our project is an ex-post analysis of the $17.6 million USAID-funded Feed the Future Nigeria initiative implemented by Catholic Relief Services across six states (Sokoto, Kebbi, the Federal Capital Territory, Borno, Yobe, and Adamawa) from 2013 to 2018.

Our project will collect data from more than 1,000 households as well as community leaders, implementing partners, and project staff through surveys, focus group discussions, and interviews. We seek to explore both the long-term impact and sustainability of Feed the Future interventions and better understand the factors that influence household resilience in northern Nigeria.

We are lucky to have been able to carry this project out in person at all due to security concerns and visa delays. Because one of our three training locations in the northeast was classified as a “high-risk level 4”, it required a security plan, extra precautionary measures, and an additional review process—we did not receive official approval until after arriving in Abuja. In addition, one teammate’s visa was so delayed she had to reschedule her flight, leaving just the two of us to kick off the project and conduct our first enumerator training.

A Catholic Relief Services focus group training with enumerators (data collectors) from Borno, Yobe, and Adamawa states in Yola Town, Nigeria. Photo by Emma Hokoda.

A new day, a new challenge

Our wahalas (“challenges” in Nigerian Pidgin—the lingua franca in a country of more than 200 million people and 500 languages) have continued and even multiplied. The first three weeks in Nigeria have been a critical training period for our team, and I can’t remember a day when we haven’t run into an unexpected problem. Each training had its own suite of wahalas, from missing team members to unexpected relocations, canceled flights, and delayed training.

The funny thing is, once you run into enough unexpected problems, they aren’t unexpected anymore. The daily power outages, unstable and sometimes nonexistent Wi-Fi, and the occasional government-led mobile phone blackouts have become a normal part of life. Each morning I wake up without expectation for how the day will go—I have learned to let go of my plans and am nimbly adapting to the wahala of the day.

While my teammates and I fought hard to get to Nigeria and have endured the daily wahalas of fieldwork, we won’t meet a single Feed the Future beneficiary. The only data collection we will do ourselves consists of a handful of key informant interviews, some of which will be done virtually. The fifty enumerators we have trained over the past three weeks will be collecting the bulk of our project data. Now that training is over, our role is shifting to a managerial one: tracking data collection progress across the six states, cleaning survey data as it is uploaded, catching and correcting errors, and forming focus groups. As the data collection winds down in two more weeks, our roles will shift again, this time to coding interviews and focus groups and running quantitative analysis on our surveys.

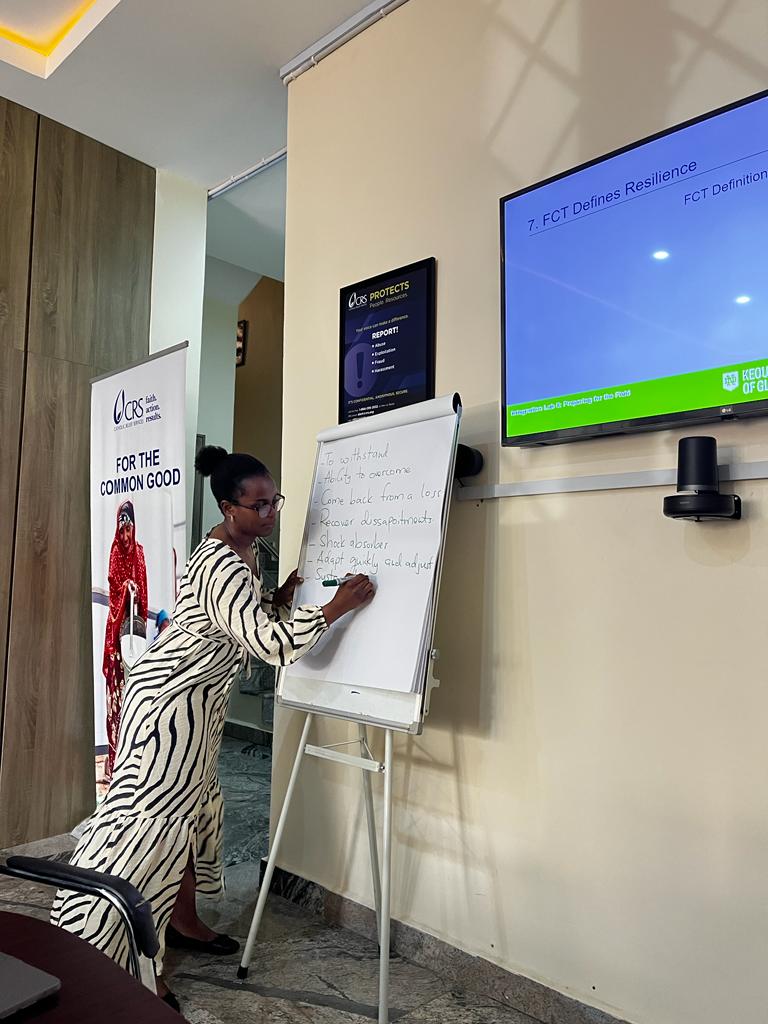

Master of global affairs student Nancy Obonyo takes notes during a training exercise defining resilience. Photo by Emma Hokoda.

While a younger version of myself would have been disappointed to feel so removed from the data collection itself, I am quite confident that this method is the right one. My teammates and I are outsiders here, and our positionality would only bias and hinder data collection. Our enumerators are Nigerians from these communities who speak the local language, and a handful were even involved with the original Feed the Future project. Their insight into the local context has further informed and improved our methodologies and the data collection instruments we built based on standardized resilience measurement frameworks. Our role as trainers is to ensure that our instruments are well-understood, used correctly, and that there are standardized practices across the board to ensure the most accurate data collection possible.

The difficult dance of data collection

I have also learned to be grateful for the unique opportunity to develop and test our data collection instruments. Implementing a project like this one is no small task, and the ideal instrument developed in your head while in the United States differs wildly from the reality that exists across the ocean. However, we aren’t dropping our instruments without looking to see where they land; we’ve carried them with us and hand-delivered them to those who will actually use them. This handoff has revealed just how much we don’t know about the challenges of deployment. Our enumerators informed us of certain survey questions that can be perceived as insensitive; that cultural dynamics prohibit men and women from being in the same focus group discussion; that beneficiaries may hold certain expectations which could bias their responses, and more.

The project also demonstrated the difficult dance it took to develop instruments that could simultaneously speak to USAID’s definition and measurement of resilience, meet our partners’ needs, be taught to our data collectors in a two-day training and adapted/translated to fit the local context, not overburden the participants, and can be analyzed by our team of three.

Are we the weak links?

As graduate students, my teammates and I have often felt like the weak link in the partnership, questioning “Why us?” Surprisingly though, CRS has demonstrated both trust and high expectations for our work. Mobilizing fifty enumerators on our project’s behalf was an incredible investment into our team and has enabled us to pursue the most ambitious project the i-Lab has ever seen. I am incredibly grateful we have such a committed team behind us, from our partners at CRS headquarters who helped guide our project proposal and data collection instruments, to the staff across CRS Nigeria who have been instrumental in hiring our enumerators and coordinating training logistics to aid our research.

Master of global affairs student Emma Hokoda (standing) facilitates a training session on reporting procedures for household surveys at a Catholic Relief Services office in Abuja, Nigeria.

While our project has been riddled with uncertainty even before we arrived in the country, this support has made this complex project feasible. The way our colleagues roll with the punches inspires me to let go of my controlling tendencies and loosen my tight grip enough to adapt to the ever changing conditions on the ground. Embracing ambiguity is a process, but I’ve never felt the idiom “Where there is a will, there is a way.” to be more true than in this project in which my team has found a way through every problem in our path.

Moving forward

We have just finished our third and final training in Sokoto and data collection has officially begun in all three states. As the initial surveys begin to roll in and we head back to Abuja for the rest of our fieldwork, I feel justified in releasing a cautious sigh of relief. I know the wahalas won’t end here, and I’m sure there will be more bumps in the road. Nevertheless, it feels good to close this training chapter, celebrate our accomplishments thus far, and officially move into the next stage of the project.

Top photo: Author and master of global affairs student Emma Hokoda (bottom right) and classmates Colleen Maher and Nancy Obonyo with Nigerian enumerators (data collectors) at a training session for Kebbi and Sokoto states in Sokoto, Nigeria.