“To take for granted” is a phrase that describes most of the actions of humanity. We take our health, fresh air we are breathing, education, and even people for granted, failing to properly appreciate them. My journey to Chile, which started three weeks late because of a visa delay—or “bureaucracy” as Chileans call it—has made me ponder this phrase and its active role in our lives.

I had heard a lot of good things about Chile, so I had very high expectations for my Integration Lab research project and was really excited when I got my visa. However, it was a little bit of a disenchantment for me to see the polluted air of Santiago and not be able to see the beauty of the city because of urban smog. While we were driving to our home, my host dad tried to show and explain the geography and parts of the capital, but most of the time we could not see the buildings or mountains.

The air became clear after several days, and I was finally able to enjoy the view of the ancient Andes, green parks and hills, as well as the beautiful architecture of the city’s buildings. This taught me to appreciate what I have. Santiago is surrounded by mountains that have witnessed centuries of history. However, the lack of wind in the city due to these mountains makes heat concentrate in the higher layers of the air, causing the smog in Chilean winter. If it rains in the city, people become really happy because the air will be clear the next day.

Chilean winter is not as cold as winters in the Midwest, yet it is cold inside the buildings. I was really lucky that my host family had a heating system in their house. Otherwise, I would have frozen in cold nights and mornings. Again, I took this type of comfort for granted until the moment that I found out that my teammates had sometimes been feeling cold in their apartments.

Learning to appreciate the little things

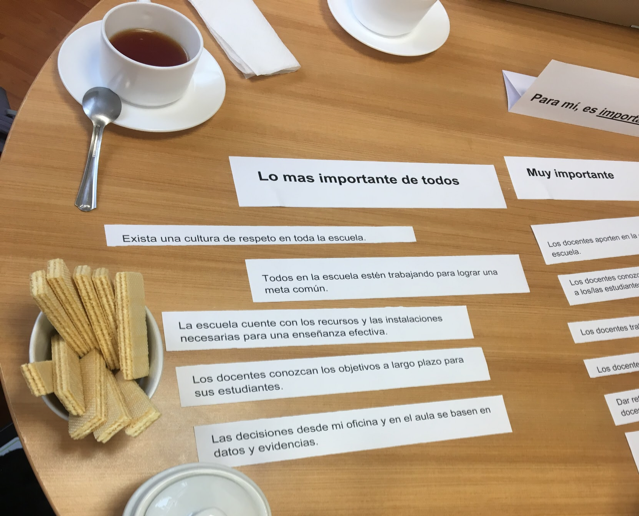

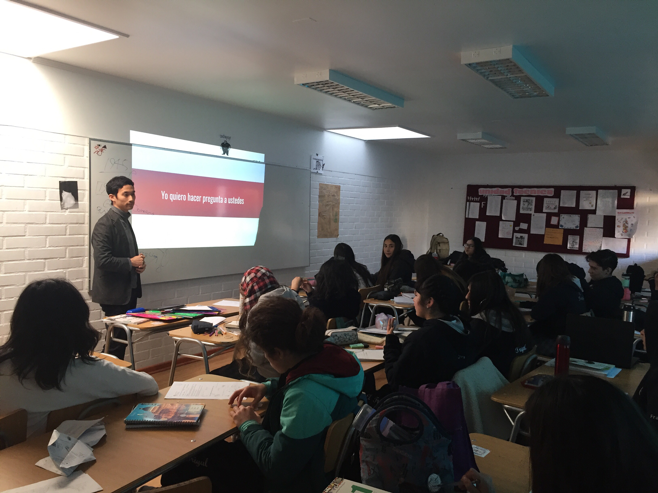

Inequality in Chile has been a topic of not only regional but also global importance. Reading articles and books about this issue is very different from seeing it up close. Social and economic inequality leads to education inequality, causing a lower quality of education at public schools. This has been a problem to work on for many for- and non-profit organizations, among which is Enseña Chile – a Chilean version of Teach for America. This NGO collaborates with public schools. Its branch Colegios Que Aprenden (“Schools that Learn”), which Seiko, Frank and I closely worked with, offers its expertise to leadership teams to improve the learning environment at their schools.

Our cooperation with Colegios Que Aprenden partner schools has revealed that school leaders have different motivations for educational improvement, as well as different priorities. In most cases, leaders need basic things like safety and security of children. Once we went to a school without any actual buildings—temporary, truck-type constructions were the only shelter. Still the children were happy. When we had a meeting with a principal of the school, we discovered that she is a really nice person trying to do her best as a principal and make the most of the situation.

Thinking about all of these things leads me to conclude that the concept of “No one left behind” is really tough to achieve. You can do your best to develop a learning environment at schools, but unfulfilled basic needs make your job more arduous. But seeing very optimistic and assiduous people facing a harsh reality and still not stopping their efforts encourages us to work hard, as well. Thus, the ability to be grateful for every little thing and keep continuing is the most important skill.

P.S. Chile does not only have negative sides. The natural beauty of this Latin American country along with its hospitable and sober-minded people made our journey unforgettable. A coin has two faces: I tried to capture the country from all angles, choosing photos to show the beauty of the country and using words to describe the experience that taught us not to take everything for granted.