by: Abeera Akhtar

“When natural disasters strike, they hit poor communities first and worst. And since women make up an estimated 70 percent of those living below the poverty line, they are most likely to bear the heaviest burdens.” – WEDO and Oxfam America Fact Sheet

My Integration Lab (i-Lab) partner, Theresa Puhr, and I reached Cambodia in the first week of June to temperatures of around 38°C. The heat combined with the humidity was more than any of us had expected. We soon learned that while summer in Cambodia had always been warm, this year was exceptionally hot, and the rainy season had not seen much rain. The culprit is no stranger to any of us anymore: climate change.

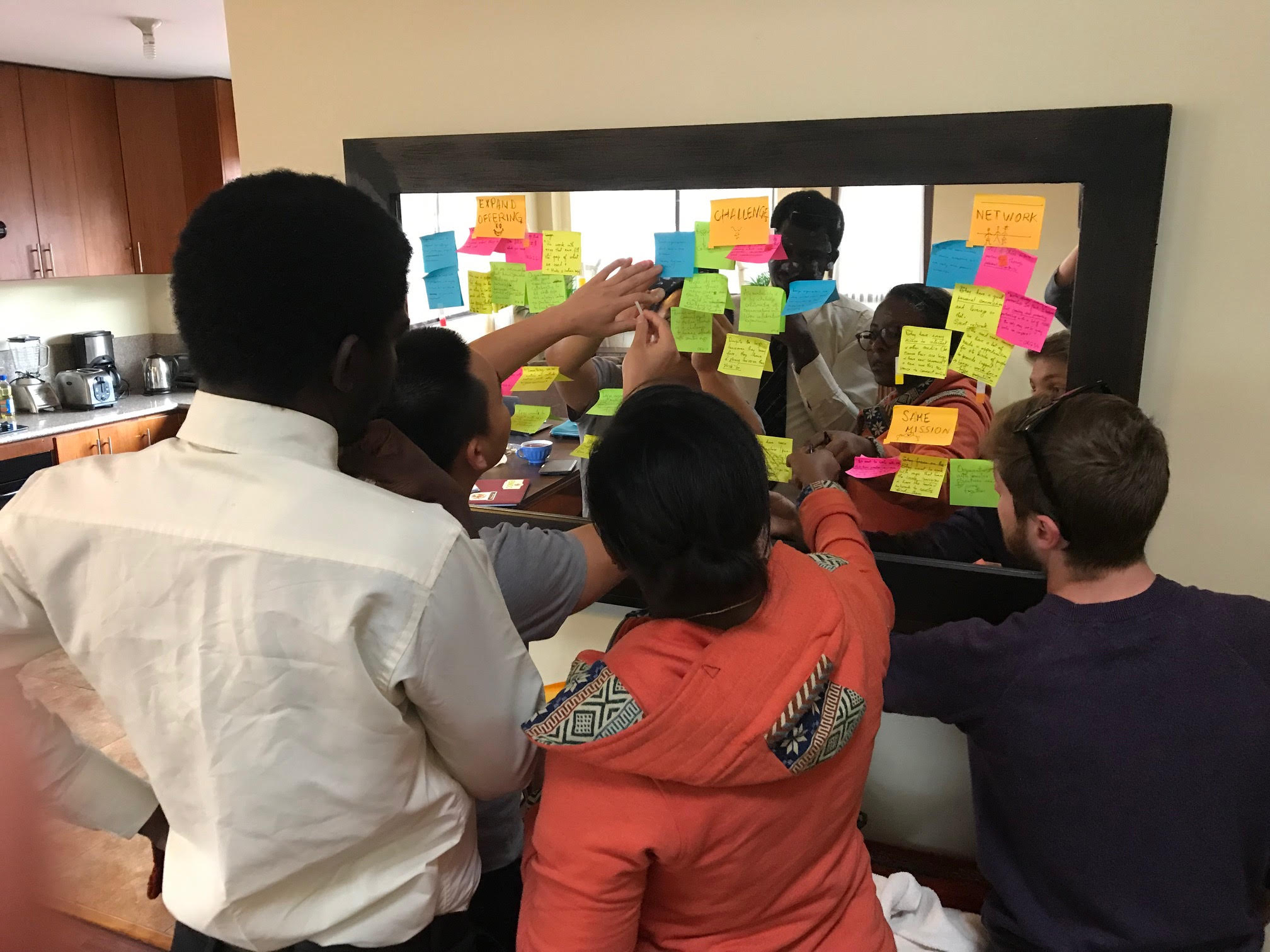

For our i-Lab research project, Theresa and I are spending the summer in Cambodia working with Oxfam to understand how women’s economic empowerment (WEE) programs work and how they can be used to challenge gender dynamics in the household and expand smallholder women farmers’ access to markets. Climate change was never something that explicitly came up as we prepared for our time in Cambodia, yet it is a reality that we could not ignore once we were here.

Though Cambodia is still recovering from the socioeconomic devastation left by the Khmer Rouge, it has certainly caught global attention for its rapid economic growth rate of 7.5% per year. As Cambodia moves away from its dependence on international aid and imports, its focus has shifted to building its natural resource industries. With a largely agrarian economy, rice is one of Cambodia’s main exports, and there is a push for the country to become the largest organic rice producer in Asia.

Most of the women farmers we have met are between the ages of 40 and 60, since much of Cambodia’s youth have migrated to cities or other countries to look for better economic opportunities. Farming is clearly a labor-intensive job, even more so because these women cannot afford machines to automate any of their work. In our interactions with them, we learned that organic crops provide a premium price, and we sensed their desire to learn about advancements in farming techniques so they could access this market. Yet changing the traditional techniques that they have grown up with is not easy. And while the process may be slow, Cambodia expects to be a force to be reckoned with when it comes to rice production in the near future.

HOW CLIMATE CHANGE HOLDS CAMBODIA BACK

Despite all the optimism around increasing rice production, each interview with the women farmers brought forth several challenges still facing the industry. Out of many, one in particular stuck with me: the changing seasonal patterns.

Cambodia has two seasons: the dry season, which lasts from December to April, and the wet season, which is from May to October. Given that rice requires a lot of water, it is a staple of the rainy season. Due to the lack of rainfall this year, many farmers have lost entire crops. While every stakeholder we met with—from development partners to the government—acknowledged climate change as an issue, just like the rest of the world, they are struggling to respond to it. And as Cambodia fast-tracks its development, climate change has become a bigger reality.

PEOPLE BEFORE POLICY

As students of the Keough School’s Master of Global Affairs program, we talk a lot about policy recommendations, how they might be implemented, and their implications as a whole. However, in these discussions about these major problems, we often lose out on how policies affect individuals and fail to fathom how far-reaching their consequences are. I truly felt this as the private sector individuals in Cambodia talked about how European tariffs and demand from China affects local rice demand—yet, the woman we met had one purpose: produce rice and sell it to make a decent living.

As every interview and focus group we have participated in talks about the changing weather and how it has affected crops, I am filled with a sense of dread. Given the current trajectory of climate change, the future looks bleak. Cambodia, along with the rest of the world, is not alone in being unprepared for the challenges that lay ahead. If we were to come back to meet the same women in five years’ time, how will climate change have affected their livelihood? Would the government have stepped up to deal with the problem? Even more so, will the needs of smallholder farmers, particularly women, be heard? Organizations like Oxfam are trying to ensure progress in this area, but with a problem that big and so many lives at stake, the real question to ask is: Are we really doing enough?