By: Prithvi Iyer

Bosnia and Herzegovina is not a place I had ever pictured myself visiting. This small country in the Balkans had quite simply never captured my imagination. Its allure was less obvious to me, unlike that of western European countries such as France and Switzerland that are often romanticized in globalized pop culture.

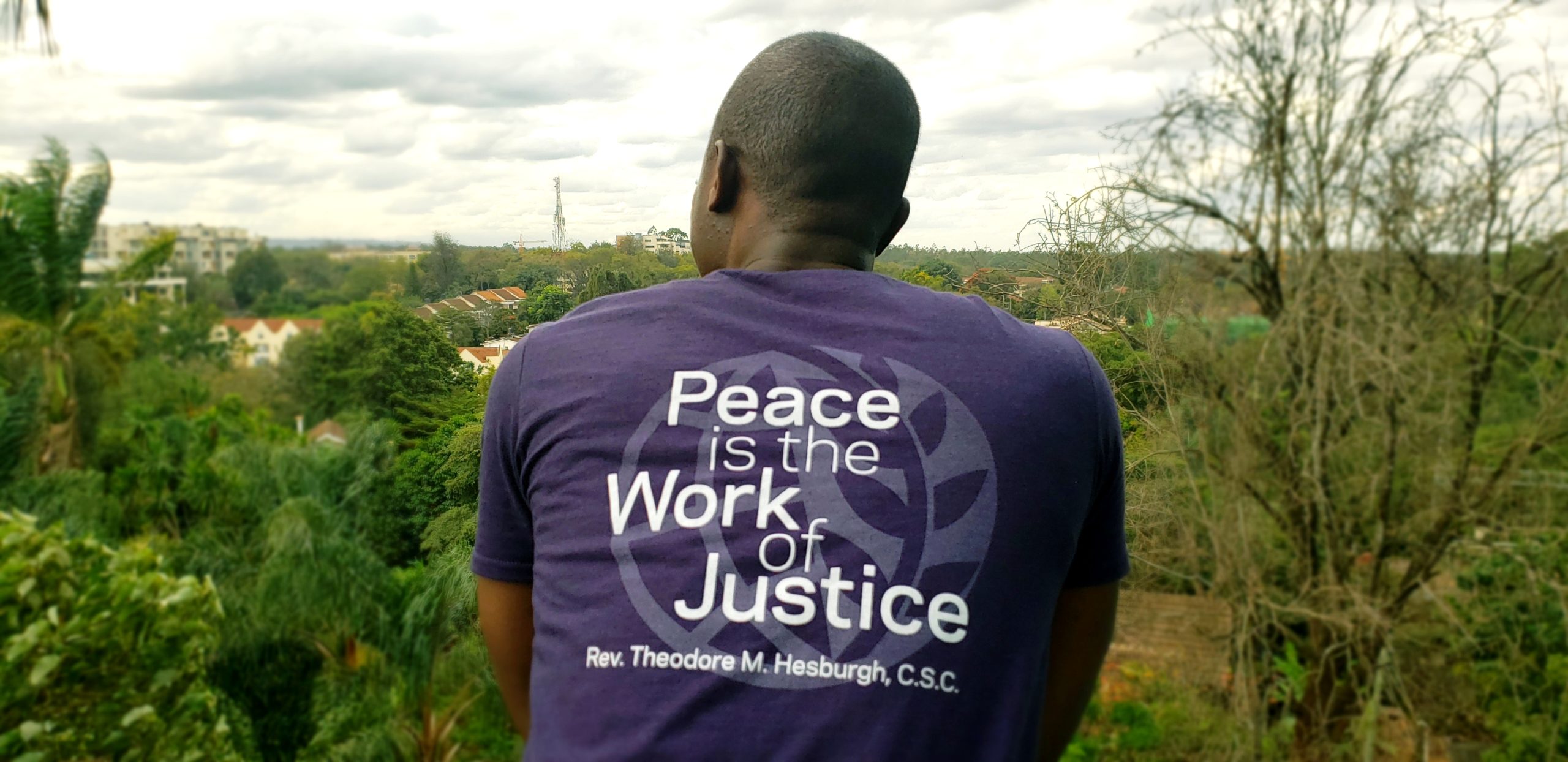

But thanks to a student trip made possible by the University of Notre Dame and Peace Catalyst International, I recently visited the country—not as a tourist, but as a student of peacebuilding who gained a new appreciation for the role of religion in peace processes and reconciliation.

In preparation for this trip, I spent time acquainting myself with the dynamics of the conflict between Serbs, Croats and Bosniaks. While this preparation was key, no number of readings could have prepared me for what I felt and learned by immersing myself in the world of the locals and their myriad experiences.

New encounters challenge old perspectives

Coming from India, I was not oblivious to anti-Muslim discrimination and its violent implications. In fact, my background provided me with an interesting comparative lens to process what local peacebuilders and students shared about the nature of violence taking place in Bosnia, especially during the war of 1992. I always thought that South Asia’s experience of discrimination and the relative ambivalence of the international community was exacerbated because the region’s population is non-white. But as a local aptly explained to me, after the breakup of Yugoslavia, being a Muslim in Bosnia has meant facing prejudice and oppression—a reality that white skin or blue eyes cannot protect against. The sobering inference I drew was that anti-Muslim prejudice can exist independently of racism.

The trip also provided me with experiences that challenged my worldview. For one, visiting Srebrenica, the site of a historically significant massacre, and seeing the detailed ways in which each life lost was documented and memorialized was unlike anything I have ever seen. Despite experiencing wars and losing many lives to conflict, India does not have similar memorials that document violence by providing it with a physical and tangible manifestation. This prompted me to wonder how narratives around victimhood in my own country may be obscured by the lack of efforts to memorialize these tragic events.

Upon contemplating how Bosnians grapple with memories of wars and the existence of memorials, I found the ways cemeteries were constructed in the middle of the city of Sarajevo to be especially fascinating. Rather than hiding these sites from view or constructing them on the outskirts of the city, planners ensured cemeteries in Sarajevo served as an integral part of the overall landscape. Our Bosnian guide told us that this was to encourage Bosnians to confront and celebrate lives lost rather than shy away from it. Children play in these cemeteries and are not scared to run through the acres of green grass that occupy these traumatic spaces. By integrating memorial sites into the visual spectacle of Sarajevo, the city’s residents ensure they will never forget the lives that have been lost. At the same time, they do not view death with something to repress, but rather something that should be confronted and normalized; to me, that is a beautiful sentiment.

My experiences in Bosnia and Herzegovina also made me introspect and critically examine the ways in which I think about religion. Most of the students in this trip had religious affiliations and the conflict in the country necessitated an understanding of religion and how they shape narratives of victimhood. Meeting local imams, priests and visiting key religious places in the country was an eye-opening experience for me. I learned that despite not having a religious affiliation, I still must empathize and put myself in spaces that constructively engage with the idea of faith. Conversations with my roommate (a devout Muslim from Pakistan) and local Bosnian students taught me that religiosity is not necessarily a deterrent to peacebuilding and often, is a crucial component of reconciliation work.

I returned from this trip not converted by religion, but having formed a deep appreciation for the place of religion and faith in healing societies fractured by identity conflicts.

Letting go of my own biases regarding institutionalized religion and delineating the oppressive potential of religion from its peaceful dimensions (which provide a bulwark against systemic injustices) had a profound impact in reshaping my own belief systems. I learned about how different denominations in the church can have varying approaches to inter-faith dialogue and peacebuilding. Meeting a Franciscan priest who spoke about how he has many atheist friends challenged my own stereotypes about religious people being closed-minded. I returned from this trip not converted by religion, but having formed a deep appreciation for the place of religion and faith in healing societies fractured by identity conflicts.

Learning from others’ stories

I would be remiss to not mention the people I met and the value of the interpersonal connections I formed on this trip. Exploring the rich cultural history of Sarajevo with local students who quickly felt like good friends was deeply enriching. Beyond conversations around the conflict we were learning about, I was intimately familiarized with daily life in Bosnia and Herzegovina, and the ways beauty can be found amid divisions and violence. Seeing people marred by conflict still live life with unbridled optimism taught me that societies can respond to historical cycles of violence with calls towards peace and reconciliation.

One anecdote that captures this beauty is my conversation with Mirela, a local Bosnian peacebuilder working with us on this trip. She spoke of how her childhood was snatched from her because of the genocide during the Bosnian War. But rather than letting that traumatic experience characterize who she is, Mirela still exudes a sense of humor and zest for life that is deeply inspiring. She told me how being a young mother now is her way of re-living her childhood. This ability to find avenues for fulfillment despite a history of trauma challenged my perception around what living with trauma should or can feel like. Conversations with amazing women like Mirela and with college students showed me how people are spearheading a push towards normalizing relations and looking beyond differences.

As I return to the United States and continue my education in hopes of aiding peacebuilding efforts, I am aware that these reflections and lessons can quickly evaporate as I get consumed in my next project or the next context in which I work. While I can’t predict the future, this trip, and the transformation it has forged have not been merely academic. My learning has been personal and affective, and has had spiritual dimensions. I eagerly hope this is the first of many visits I can make there, and I hope more people at the Keough School and beyond get to experience the richness Bosnia and Herzegovina has to offer.

Top Photo: Prithvi Iyer enjoys a hike during a recent student trip to Bosnia and Herzegovina.