by: Djiba Soumaoro

In Malian French, we have an expression: “Le cordonnier est le plus mal chaussé,” or “the shoemaker wears the worst shoes.” The English equivalent might be: “The plumber fixes his own pipes last.”

I got to thinking about these aphorisms during my daily commute on foot from my apartment in Baltimore’s upscale Mt. Vernon neighborhood to Catholic Relief Services (CRS) headquarters near the seedy Lexington Market. As I approach, beggars ask for spare change, the homeless huddle in doorways, alcoholics congregate around a liquor store, and drug-addicts wander aimlessly or are occasionally sprawled on the sidewalk. This despondency is the face of America’s violence.

My six-month internship with CRS, part of my Master of Global Affairs program at the University of Notre Dame, has afforded me an extraordinary opportunity to learn about peacebuilding. For the past six years I’ve lived in the U.S., but I was born and raised in Africa. My wife is Malian, like me, and we have a lovely baby girl.

I like my hometown of 20,000 people in rural southwestern Mali. From a distance it looks like a large village at peace with itself on the rolling savanna. Up close, however, it’s violent. Girls do not graduate, we don’t trust each other, we suffer chronic food shortages, malaria kills our young and old, youth no longer respect elders, and religious leaders fail to inspire. Corrupt, despotic government is normal. When I left Mali, I didn’t understand the inherent violence in these realities. I knew nothing about modern peacebuilding, but I knew some traditional peacebuilding strategies.

I count myself fortunate to have landed on CRS’ Equity, Inclusion and Peacebuilding (EQUIP) team. EQUIP consists of a handful of staff dedicated to improving life conditions for overseas youth, women and girls, and anyone who is marginalized and oppressed. EQUIP members are experts in governance, protection, gender, and peacebuilding. Within EQUIP, I was assigned to the Africa Justice and Peacebuilding Working Group (AJPWG), which focuses on Sub-Saharan Africa. Its five members–three of whom are based on the Continent–provide technical assistance to CRS’ field offices, to the Catholic Church and its networks, and to local partners in Africa. They develop tools and methodologies based on lessons and best practices. I find this work interesting and stimulating.

When I arrived at CRS, I had many of the traditional worries of an intern: How could someone like me do anything useful? Would CRS benefit from my internship? But I soon had little time for such preoccupations.

I began drafting an annotated bibliography for case studies involving CRS’ youth, elections, and peacebuilding projects in Ghana and Liberia. I conducted research on Preventing and Countering Violent Extremism (P/CVE) in Mali. I developed an outline for my capstone project on youth and religious leaders in Mali. I became so busy that when it happened, it took me by surprise. I was poised to experience an epiphany.

Soon after my arrival, my CRS mentor invited me to attend the AJPWG’s annual Institute for Peacebuilding in Africa (IPA). The IPA was a week-long workshop that covered the basics of peacebuilding—Peacebuilding 101—all the things you would want to know if you were thrown out in a conflict zone and asked to design a project. Nearly 500 people have taken the workshop since 2009. This year it was going to be held in La Somone on Senegal’s Petite Cote, about 600 miles from my hometown. Twenty-three development professionals representing a dozen countries in Francophone Africa came, and I would be able to visit my family after the workshop.

My group was the first to use the Peacebuilding Fundamentals Participant’s Manual, a document comprising the basic IPA curriculum. It was full of helpful tools and exercises. That was the good news. The bad news was that I had to stand up before my peers and lead sessions. Among other things, my job was to explain the John Paul Lederach triangle! Despite my fears, I discovered that teaching is the best way to learn and practice new skills. Fire hardens steel as they say. It prepared me for what was to happen in the coming days.

As I travelled across the Sahel, I reflected on “learning by doing.” I had survived the scrutiny of my peers. It felt exhilarating. In Baltimore I had already begun to reflect on conflict in Ouelessebougou, Mali—my community. How could I get involved? What tactics and tools would be appropriate? How would I use them? At the beginning of my internship, I never imagined what occurred to me now. I had the tools I needed in my backpack: the Peacebuilding Fundamentals Manual. I could get started.

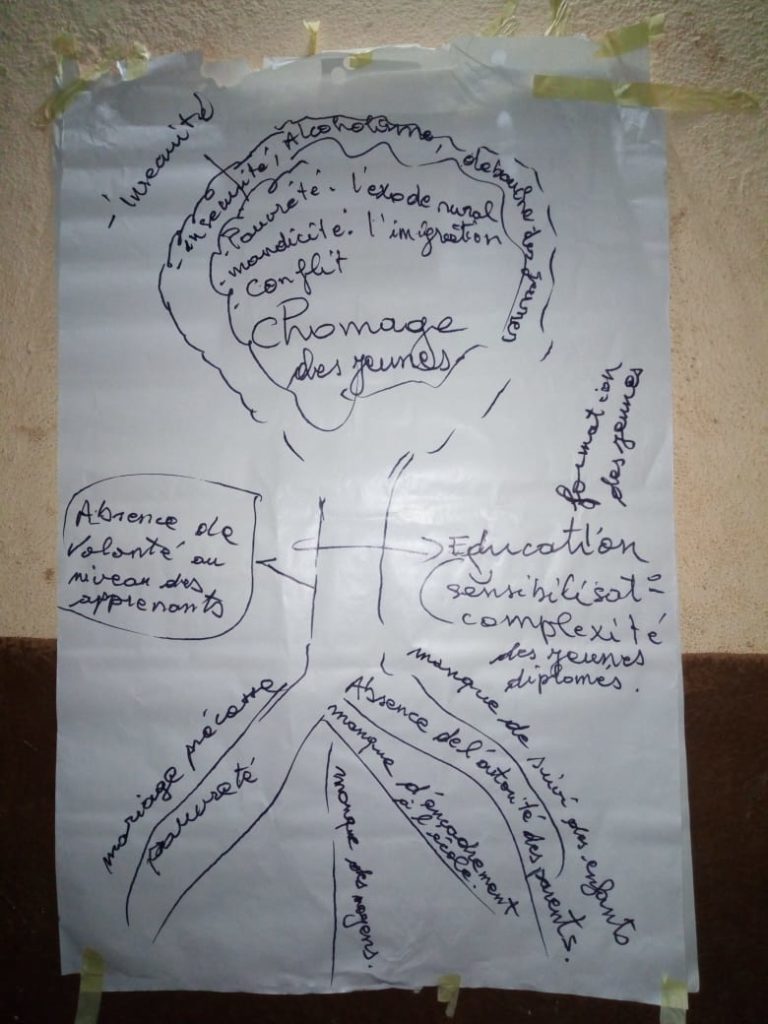

I needed to act quickly. I only had one week. Representatives of 10 youth associations and the largest women’s associations in Ouelessebougou gathered at the Youth House. Using the “Conflict Tree,” the participants identified two major issues and mapped their root causes and consequences. The participants linked the mismanagement of schools and a dysfunctional school system to extreme youth poverty. We found that a lack of education was causing high youth unemployment which self-serving politicians were manipulating to create insecurity in our community. Young people no longer trusted each other. Relationships were broken. Parents were apathetic about their children’s education.

Emboldened by their progress, the women and youth suggested follow-on activities. How about a connector project? What about a youth entrepreneur program to create jobs and discourage political opportunism? Could I return to conduct three trainings or workshops per year? Why not use the Conflict Tree to analyze problems in the household? The region? At the national level? Participants later approached me and thanked me profusely. It was the first time that women and youth had come together to discuss common issues and solutions.

The following day, Ciwara, our community radio station, featured me as a guest. How could young people be inspired to pursue higher education and change their lives in positive ways? How could parents be encouraged to care about their children’s education? Many young people quit school to make quick money panning for precious metals and stones. Few got rich and some returned with disease, pregnancies, and divorces. Awareness-raising and education were needed. Like a tree, education would offer a long-term investment bearing fruit and nuts over time. I gave examples of people who had struggled, who made such investments, and how education had changed their lives. They had been children of farmers, blacksmiths, and well diggers. A child born in lowly circumstances could become an ambassador or a minister.

After the broadcast, several people greeted me at my family’s home. Some parents told me that my radio talk had opened their minds. They were persuaded that they needed to care far more about educating their children. Some people were so taken by the discussion that they called the Station Director to request weekly programs on this topic. I reflected that the IPA had motivated me to take action and enabled me to make a real difference in my home community.

I returned to CRS in October and resumed my daily routine. I saw the police handcuff someone on the streets. I saw the drug addicts, and I read about mass killings. I asked myself: Why are Americans unable to solve gun crimes and drug problems in their own country? Why do they spend so much money to solve violent conflict overseas? Could the federal government and the City of Baltimore work together to resolve violence? How is it that a power like the United States, able to help other countries reduce violent conflict, cannot stop police brutality, drug abuse, and mass incarcerations on its own shores?

I have no answers, but I wonder how long it will take for public places to become safe and peaceful in the U.S. Could the same social cohesion and conflict analysis tools I used in Ouelessebougou help identify the root causes of gun crimes and mass shootings in Baltimore? Malians and Americans share the same sense of urgency regarding social problems, and maybe the tools and solutions are not that different.