“India is diverse and multifaceted. You can drive 100 kilometers away from Chennai and find yourself in a completely different context and culture.”

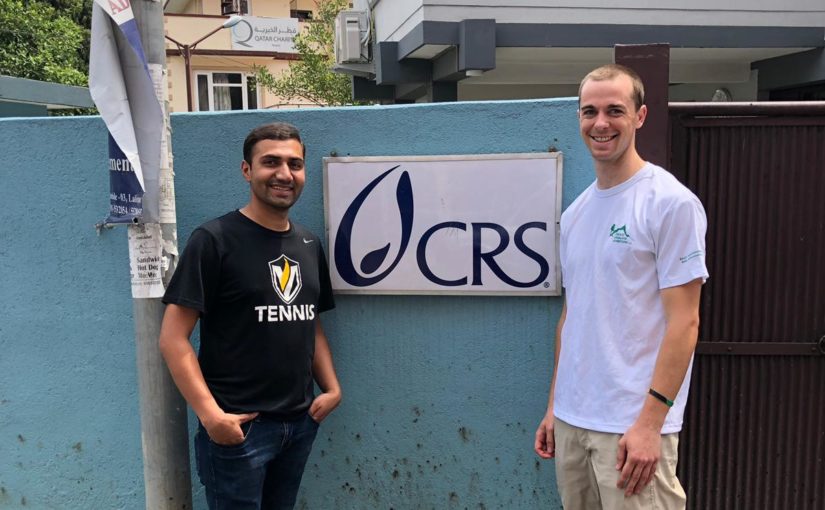

Local staff of Habitat for Humanity’s Terwilliger Center for Innovation in Shelter shared this truth during our first office day in Chennai, India.

The Terwilliger Center seeks to facilitate affordable and dignified housing through inclusive market systems. My teammates and I are working with the Terwilliger Center through the Keough School’s Integration Lab (i-Lab) to develop a methodology that would allow them to conduct behavior change interventions in the construction sector. We have been working in India and Mexico.

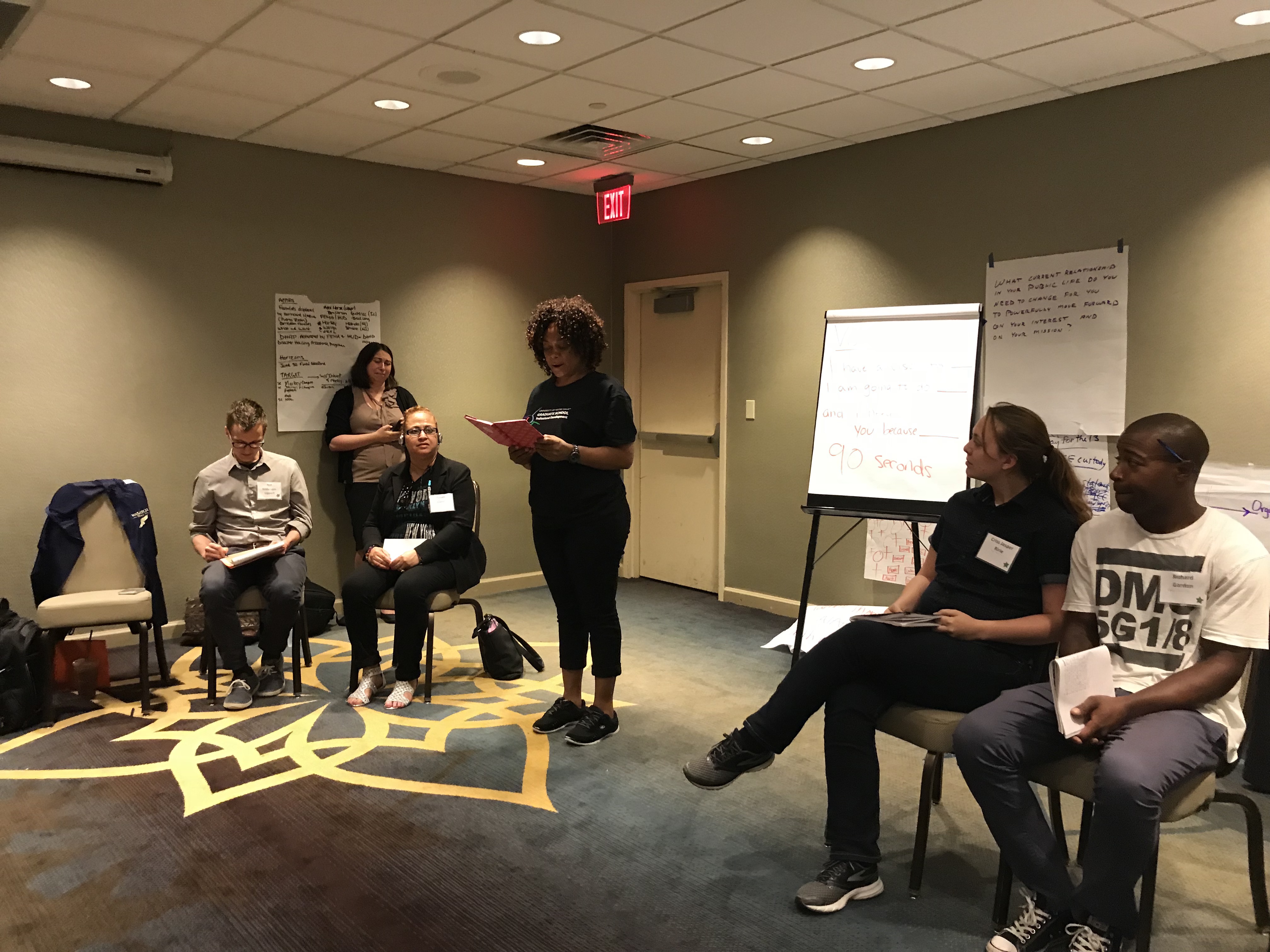

Our partnership with Terwilliger Center’s local offices in Chennai and Mexico City has proven to be invaluable. While we were able to share our knowledge of design thinking, behavior change, as well as civil engineering (thanks to our teammate Mayra and advisor Tracy), not only did we receive a technical education in construction practices in both countries, but also immense support on the ground. We had the privilege to interview, interact with, and listen to dozens of local families, construction workers, as well as multiple stakeholders of the construction industry. While design thinking tools, which we have learned about over the course of two previous semesters in the i-Lab, have helped us to develop a more nuanced understanding of the target group, the local expertise that the staff brought to the table made the collaboration most fruitful.

HOW BEHAVIOR STUDIES INFORM DEVELOPMENT WORK

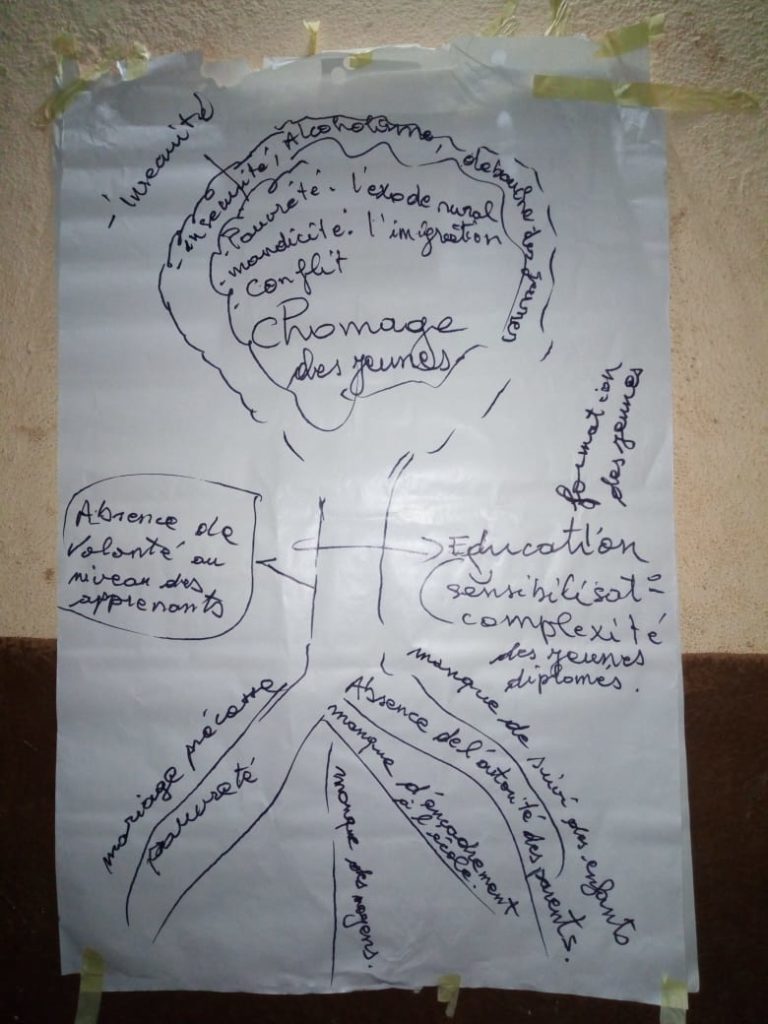

Behavior studies, a field that attempts to understand human behavior through an interdisciplinary lens, is becoming increasingly popular across different sectors ranging from public health to product marketing. The development field is not an exception, as more organizations seek to incorporate a behavior change framework into their work. Realizing the potential behind this approach, the Terwilliger Center wants to be one of its pioneers in the construction sector, where this framework has not been used widely yet.

To make the behavior change interventions successful, one has to fully grasp the causes of the behavior, as many attempts at changing fail due to incorrect assumptions. Simply raising awareness about behavior or creating incentives is often not enough, as a behavior is often bolstered by an intricate network of psychological, cultural, and social factors that might be invisible to those outside of the community. This challenge is still at the core of many development efforts, as lots of well-intentioned outsiders attempt to implant solutions that might not only fail to work but actually harm the local community.

Aware of this challenge to epistemic injustice, which we have learned about in classes at the Keough School, our team has been cautious in understanding our role coming as foreigners to a context replete with myriad complexities. I still remember one of our faculty at Notre Dame asking us, “Why and how as outsiders do you exactly want to change the behaviors that have been in these places for centuries?” Indeed, knowing the context is important, but even this knowledge might not prove to be enough. For any solution to be sustainable, not only do you have to know the context, you have to live through it. Therefore, while we read numerous reports to prepare ourselves for the trip, our textbook solutions will be overshadowed by the real experience we encounter on the ground.

SUPPORTING GRASSROOTS INNOVATION IN GLOBAL COMMUNITIES

Throughout these two months, our team has tried to remain cognizant of our role in the project: as an external group, we are not the ones to come up with solutions, but rather support the local offices in creating their own. Ultimately, our methodology is a process-oriented project, which we hope will be helpful to the Terwilliger Center with their future initiatives.

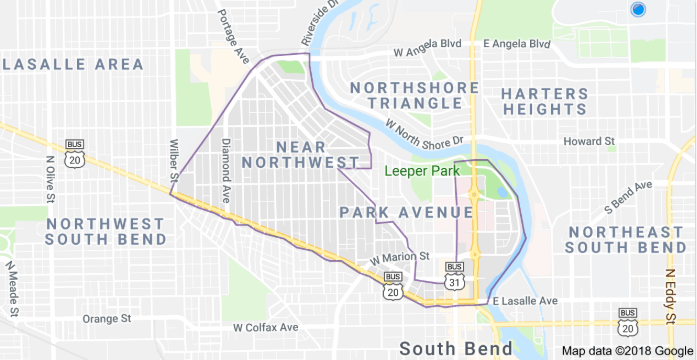

Context plays an important role in developing our methodological tools, as well. Similar to how dangerous it is to make a conclusion about any situation based on a single story, it is also dangerous to build any methodology based on one context and then try to apply it somewhere else. Being able to travel and to test our tools in two countries has only highlighted the importance of a comparative perspective.