by: Kara Venzian, Syeda (Fiana) Arbab, Sofia Piecuch

One of Catholic Relief Services’ (CRS) mottos is to “embrace the uncertainty.” Unbeknownst to us, this mindset would assist us, the “CRS Homies’—Syeda (Fiana) Arbab, Kara Venzian, and Sofia Piecuch—in navigating the reality of the coronavirus pandemic. As part of its 2030 Vision, CRS plans to shift its disaster response from a focus on “shelters and settlements” to “homes and communities.” CRS tasked our i-Lab team with gathering data to understand how refugees and internally displaced persons (IDPs) perceive and create “home.”

When the quarantine began, our team was required to pivot from our original project implementation plan to our plan B. Plan B was designed for us to delegate leading the research to local CRS staff while relying completely on local data enumerators, transcribers, and translators. As project managers from afar, we needed to be creative in assessing the capacity of our three different field teams, catering our communication to their needs, and being intentional about building relationships with them– all while navigating the uncertainty of the pandemic.

While our initial start date for research was mid- to late May, lockdowns and restrictions were extended repeatedly, ultimately delaying our research in Uganda by two weeks and in Myanmar by a whole month. Our pre-pandemic proposal sought to conduct six focus groups, six mixed method activities, 40 interviews, 20 photography sessions and 200 surveys per country. However, in light of the increasing COVID-19 cases around the world, we simultaneously elaborated a plan B and C.

Plan B involved remote data gathering with local field staff by completing six focus groups, 40 interviews, 20 photography activities, and 90 surveys per country. Plan C required us to go completely virtual in data gathering, utilizing platforms like WhatsApp, Zoom, Microsoft Teams, and remote survey platforms like Mechanical Turk, targeted to our countries of interest, as backup plans. We were prepared to implement either plan on any given notice, and ultimately were able to implement Plan B. Nonetheless, when embracing uncertainty, local conditions with layered complications had to be considered.

Due to lockdowns, refugees in Uganda and IDPs in Myanmar faced rising tensions at the intersection of poverty, food insecurity, access to information, and complications from large informal economic sectors (such as migrant workers crossing borders for temporary jobs). Furthermore, refugee and IDP camps and settlements face higher rates of health issues, sometimes having up to 60 times higher mortality rates when compared to host countries. In addition to pandemic-related complications, each refugee and IDP context faced its own challenges due to climate change, civil conflicts and war, food insecurity, poverty, corruption, and coordination failures. These difficulties were also coupled with uncertainties that arose from natural disasters.

Uganda experienced widespread flooding amid our research, while Myanmar also faced flooding and a devastating landslide during our planning stages. Myanmar was particularly impacted by COVID-19 during the summer, and both countries were stressed by the reduction of funding caused by the pandemic–especially the refugees in Uganda, who had their food rations cut by a third.

Our team sought to navigate these conditions in a way that our research could be implemented effectively without being extractive or ignorant of these realities. We intentionally built our research instruments in a trauma-informed way, actively avoiding any questions that could bring forth bad memories, and reviewed each question extensively with in-country staff to maintain our ethical commitment to the dignity and well-being of people we engaged in this research. In general, we had expected refugee and IDP camps and settlements to be ever-changing and uncertain landscapes to navigate, but we could have never anticipated to what extent.

This disaster-stricken reality required flexibility of deadlines for staff members who were constantly pulled in multiple directions to manage many emergencies at once. Additionally, when coordinating with remote staff under pandemic conditions, an immense challenge was navigating the time zone difference. Our working day in Uganda began at 2am and ended at 9am, while in Myanmar work began at 10:30pm and ended at 6:30am. At many points we were working in both countries, juggling late night meetings with Myanmar and middle-of-night meetings with Uganda, all while balancing our own personal commitments based in the States.

We recognize how unsustainable it is for our physical and mental health to be actively engaged in this work around the clock like this. Fortunately (for this reason), we spent a maximum of five weeks working in each country, with the finish line never feeling too far off, giving us something to count down to: a regular sleep schedule.

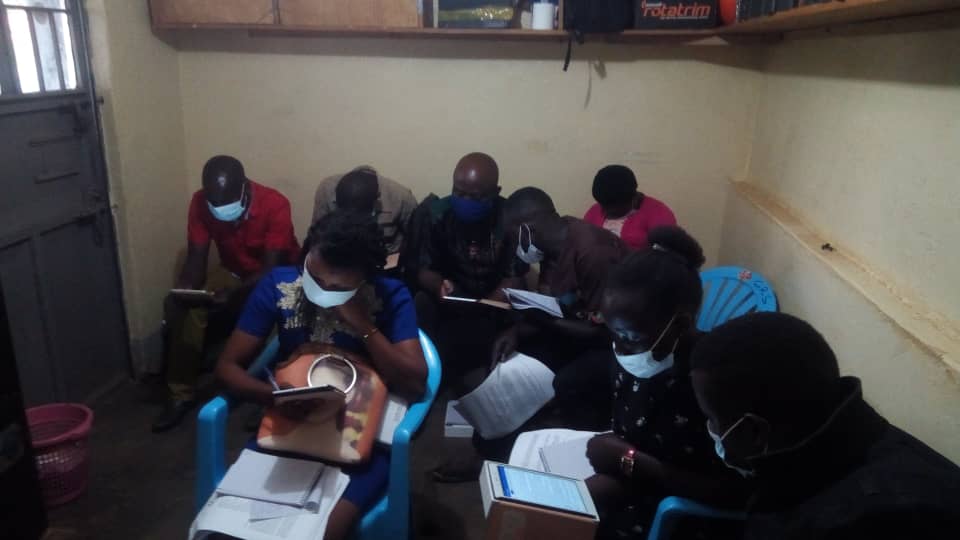

In addition to difficulties with time zones, managing a remote staff also had its complications. Each time training was conducted, we veered from the plan in unexpected ways. Internet connectivity issues caused disruptions during training sessions as well as late starts. Local conditions (for example, the weather) determined whether to collect data on any specific day. Lack of clear communication coupled with the time difference occasionally delayed research, where we had to adjust our expectations and add extra days of hired staff time in order to meet our desired number of observations. Awareness of cultural differences was vital for delegating tasks to staff and achieving results. Furthermore, knowledge of local contexts was necessary to communicate, not only with staff members, but also with key informants (“who could have guessed the UNHCR representative preferred to be contacted over WhatsApp?”).

To be accessible in real time and to bond with our local teams, we decided to coordinate with staff in a more casual way. In Uganda, we created a WhatsApp group where we could discuss daily assignments and give immediate feedback (when we were awake).

For Myanmar, we created a Facebook Messenger group. Among all teams, we insisted on finding ways to be personable despite the distance (and screens) between us—we regularly sent selfies of ourselves working, and would often receive them from the team having breakfast or in training sessions together. This interaction was one of the highlights when managing our teams; we loved to put names to faces and to personalize our engagement beyond familiarity with their titles of “enumerator,” “translator,” or “transcriber.”

These informal chat groups also bridged an equity gap, as not everyone on our staff had email accounts; many were refugees themselves and did not have access to laptops. Thus, the less-formal interaction pathways were the most accessible way to communicate, especially instantaneously.

Our distance required us to rely heavily on our excellent staff, without whom we could not have effectively conducted the research. We had to be prepared to adapt to their varying levels of expertise—with some being familiar with CommCare (our data collection app) and some having no familiarity at all—and worked to capitalize on their strengths. Additionally, we recognized that our project was one of several for some people, who, especially during the pandemic, were juggling many responsibilities. Therefore, we learned to adjust to differing levels of responsiveness from field staff. There were some points where our team had to relinquish control and let whatever was going to happen, happen. We became familiar, although never comfortable, with the chaos this distant management required, and learned to live with it.

Our State-side daily realities also provided challenges. For example, internet limitations confined us to the same space during workdays, demanding creativity when we had multiple meetings at the same time. Though our desire was originally to find an official office space, we have instead been able to use one of our members’ studio apartments (which has proved ideal, especially during overnighters). Countless key informant interviews were conducted in our workspace’s closet, as the studio apartment did not provide different spaces to operate in while conducting separate meetings. Without the support of each other, solutions like this could not have come about. We are grateful to have been a part of such a flexible team that has had a strong dedication to this project.

Ultimately, this project demanded flexibility from us in ways we never expected, and forced us to generate innovative strategies to address any uncertainties that arose. Here are some of our key takeaways:

1) We are glad that we made the decision to work together in South Bend. Without in-person cooperation, our work would have been less cohesive, less enjoyable, and less efficient.

2) Through messaging apps, email, video calls, and final debrief dinners (and selfies), we are glad to have gotten to know the 34 staff members that we worked with. This allowed us not only to receive quality work from field staff, but also gave us the opportunity to contribute to their professional development through the creation of professional certificates, resume pointers, and passing along potential employment/education opportunities.

3) Along the same lines, we observe that working remotely and relying on local staff contributes toward sustainable, localized efforts and responses.

Despite the challenges, we have still been able to receive high quality data. We cannot be more grateful for a huge challenge well met and a successful project, one that has broadened our knowledge of project implementation. We recognized all of these uncertainties and have loved the process of being uncomfortable while growing our own capabilities as project managers and consultant-researchers.