By: Emma Jackson

The name “Vichy” carries a lot of baggage. Some think of the expensive skin care brand or the historic thermal spa city frequented by Emperor Napoleon. Others immediately think of the pro-Nazi collaborationist “Regime de Vichy” and “État Français” that existed from 1940 to 1944.

Vichy is a small city in the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region of central France. It was recently named a UNESCO World Heritage Site in the category of Great Spa Towns of Europe. So naturally, at the time of my recent three-week stay during a university break, this element of Vichy’s identity was prominently marketed.

Supported by an Advance Language Training grant from the Keough School’s Nanovic Institute for European Studies, my time in Vichy helped me improve my French language skills and dig deeper into the city’s complex history.

Some historical background

After the Nazis invaded France in 1940, France and Germany signed an armistice that effectively split the country into two zones: the German military occupation zone and the so-called “unoccupied” or “zone libre” (free zone). Following the armistice, a puppet government was quickly formed within the zone libre in Vichy from an agreement between Hitler and French Great War hero Marshal Phillipe Petain.

While there is still some disagreement in France over the role of the Vichy Regime in the persecution of European Jews, recently declassified documents confirm that rather than acting out of self-preservation, the Vichy collaborationist government was a willing participant in the Holocaust. The Vichy government initiated anti-Semitic policies, such as removing Jews from the civil service and seizing property, even before the Nazis demanded their cooperation. It also willingly carried out large-scale arrests and deportations: some 77,000 Jewish French citizens and refugees were sent to death camps.

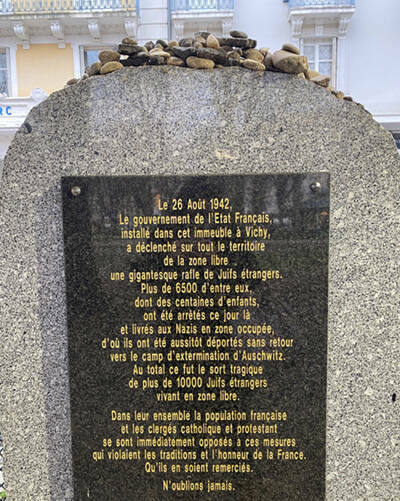

While researching this history, I found that France remains divided over the role of the Vichy government and there are multiple interpretations of the level of collaboration and the severity of the government’s crimes. In Vichy, there stands a memorial to the victims of the Holocaust, but even this epigraph displays lower deportation numbers than official estimates. It also only mentions “Juif étrangers” (foreign Jews), brushing over the fact that Vichy France also arrested and deported Jewish French citizens.

In recent news

A far-right candidate for the recent 2022 French elections, Eric Zemmour, a French Jew, has made some controversial statements about the Vichy government. For example, he claims that by first deporting foreign Jews to Germany’s death camps, Petain helped “save” French Jews. Zemmour was recently convicted and fined for racist hate speech against unaccompanied child migrants, describing them as “thieves, rapists, and murderers,” and is known for his incendiary remarks and staunch anti-immigration, anti-Islam rhetoric.

Zemmour and other right-wing politicians favor protectionist policies and are generally “Eurosceptics” (that is, critical of the European Union). There are some interesting similarities with the Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) party in Germany—founded by Eurosceptic former members of the Christian Democratic Union (CDU)—which is now regarded as Germany’s anti-immigration party.

While this visit was my first time in France, I quickly realized that far-right political parties in France promote similar agendas to far-right parties in Germany.

During the weeks I was in France, the country had taken over the European Union’s rotating presidency for six months starting in January 2022. One day after France’s presidency began, the government removed an EU flag that had been attached to the Arc de Triomphe in Paris and had attracted criticism and protests from right-wing politicians. Marine Le Pen claimed that “replacing the French flag at the monument was an attack on the country’s identity,” and Zemmour called it an “outrage.” Before my flight to return to the US, I stayed in Paris and walked by the Arc de Triomphe and other major attractions. Interestingly, while the flag was removed, the Arc de Triomphe, the Tour Eiffel, the Notre-Dame de Paris, and the Hotel de Ville (City Hall) were all lit up with the EU flag’s distinctive blue and its gold stars.

From the outset, I was interested in studying the French language in Vichy because of the Régime de Vichy’s complicated and dark history from 1940 to 1944. Living in a city with this historical memory of the Holocaust and its dark legacy of faith-based discrimination and anti-Semitic policies informed my research on right-wing nationalism, Islamophobia, secularism, and the development of xenophobic policies in Europe. The recent news regarding the right-wing candidate Eric Zemmour, the widespread protests over vaccine mandates, and reactions to the EU presidency certainly made the experience more memorable and helpful for my academic research.

Emma Jackson is a master of global affairs student in the Keough School of Global Affairs at the University of Notre Dame. During Notre Dame’s winter break, she undertook immersive French language training at CAVILAM Alliance Française in Vichy, France.

Top photo: Emma Jackson in front of Cathédrale Notre-Dame de Paris, which is lit with the blue background and yellow stars of the European Union flag.

Originally published by Emma Jackson at nanovicnavigator.nd.edu on June 03, 2022.