by: Maria Isabel Leon Gomez Sonet

Given my current interest in the links between structural violence, inequality, and transitional justice, the Institute for Justice and Reconciliation (IJR) in Cape Town, South Africa, has been the ideal place to carry out research for my MGA capstone project. Initially, my inclination was to choose a Latin American country, given that all of my professional and academic experience up to that point had focused on Latin America, particularly on human rights and U.S. foreign policy in the region. However, I decided that, given the opportunity to conduct research as part of my Master of Global Affairs program, I should do so in a new context to compare, learn, and analyze solutions carried out by other countries for problems similar to those in my own region.

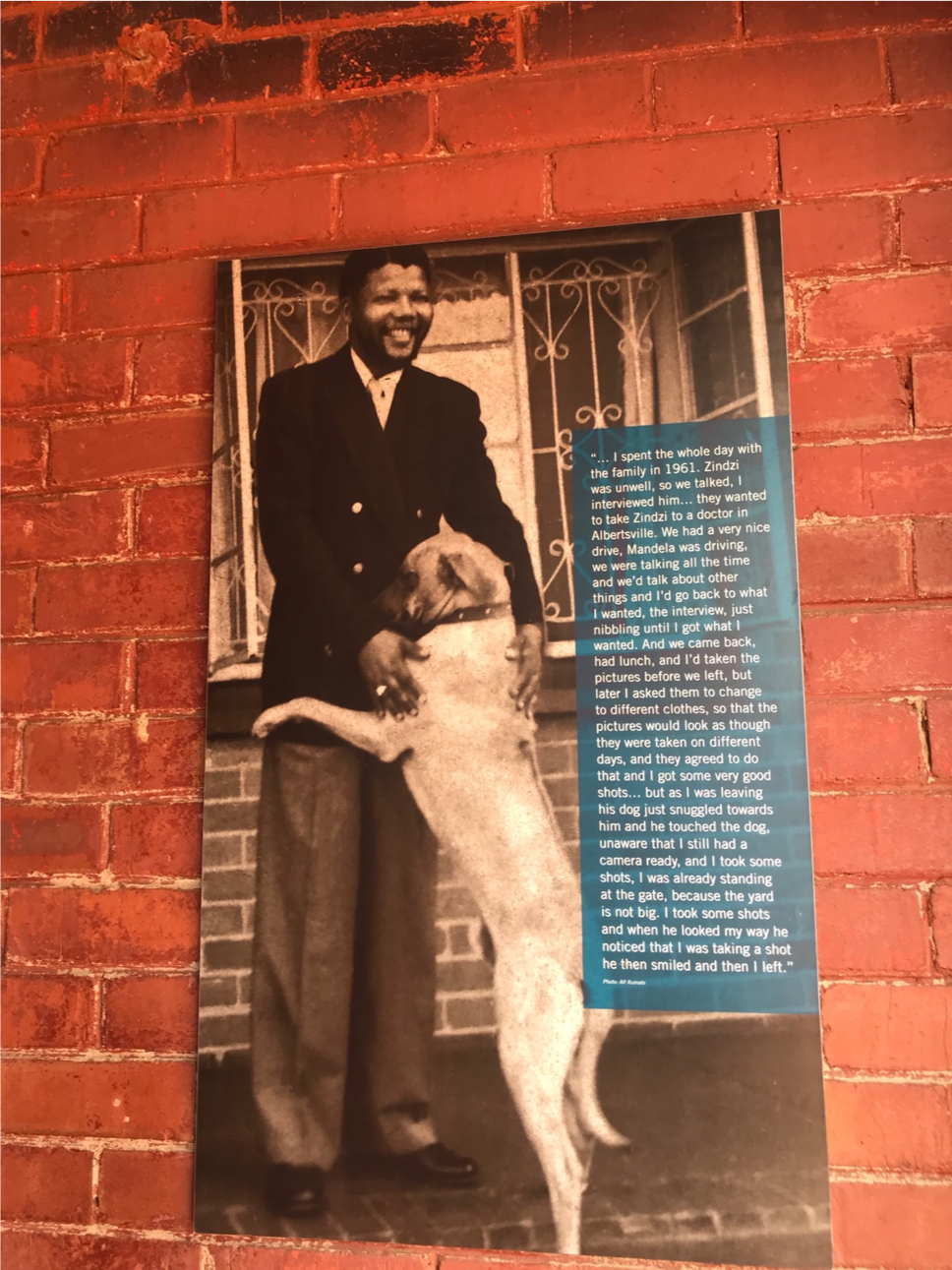

Understanding South Africa’s history

As I read about South Africa in a post-apartheid era, one thing was clear to me: the peace negotiations and the transitional justice process—mainly focused on the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC)—were successful in stopping direct violence, leading to democracy and the creation of a new constitution. The constitution appears comprehensive and inclusive of all South Africans; however, the promises of change mostly remain on paper and the structural foundations of apartheid are still in place.

South Africa is the most unequal country in the world. This inequality results in huge socioeconomic issues such as poverty and unemployment as well as limited access to basic services such as health, sanitation, and education for the majority of the Black population.

South Africa and Guatemala: Cases of Historical Inequalities unaddressed during Transitional Justice Processes

As I now study the South African case, I find connections with the Guatemalan case, a country where a comprehensive peace agreement was finalized in 1996 after years of civil conflict.

Prior to joining the Keough School, I worked in Guatemala and saw firsthand how, despite an inclusive peace agreement signed almost 25 years ago, the indigenous people (who were the main victims of the conflict) are still living in poverty, marginalization, as well as enduring criminal violence and militarization. Both countries have a deep history of embedded racism and inequality, which to this day remain unsolved behind promises of peace and reconciliation.

My research is a case-study-based approach regarding South Africa and Guatemala. I focus on moments of missed opportunities, turning points, and failed policies that resulted in the inequality and structural violence still present in both cases—even after inclusive transitional documents. I would like to explore these questions for both cases, keeping in mind the economic and political contexts, as well as the international and external pressures both countries faced at the time of transition. As I collect my data in South Africa, I have five topics of emphasis that transitional justice processes fail to address: socioeconomic inequality, gender justice, security reform, mental health, and issues of land and other natural resources.

Comparative findings thus far

In the case of South Africa, the TRC’s narrow and legalistic definitions of justice and violence resulted in the recognition of only 22,000 official victims of human rights violations. The millions of people that suffered systemic structural violence during the apartheid years were not counted as victims. For instance, during apartheid, more than two million people were forcibly displaced from their homes and land. However, these displacements were not taken into account as violations and therefore not subject to policies of reparation. In Guatemala, promises from the State to recognize the rights of indigenous peoples and to address historic inequalities remain on the papers of the peace agreements.

Both countries face ongoing issues such as violence against women rising at alarming levels. High levels of criminal violence and gangs leading to the militarization of poor and already vulnerable communities are present in both. Gender justice, as well as important reforms to the security sector, did not occur during transition periods. In both contexts, issues of healing, addressing trauma, and psychosocial as well as mental health problems stemming from violent conflict and structural violence have been superficially addressed by the State and seen mainly as the responsibility of civil society.

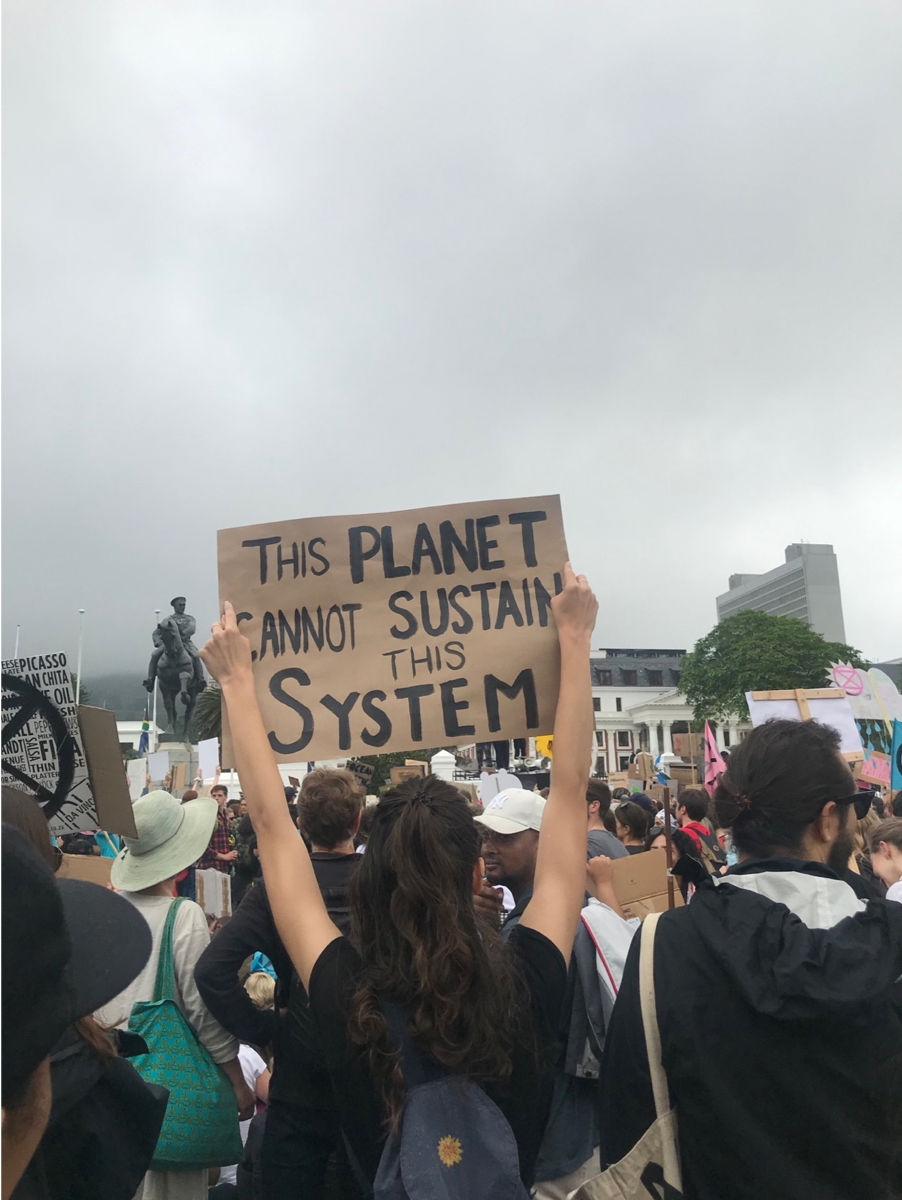

As we have learned in the International Peace Studies concentration coursework, achieving peace is not only about stopping direct violence. We refer to this as negative peace (as per the work of Johan Galtung). Positive peace is inclusive of transforming oppressive systems that will address systemic injustices and inequalities.

The exclusion of socioeconomic issues, gender, land, trauma, and security sector reform from transitional justice is not accidental. Transitional justice processes have been historically important to document and disclose the truth behind massive human rights violations. However, these processes often aim for liberal constitutional democracy and market economy as their end goal.

Transitional justice should be a long-term process—rather than a truth commission with a deadline—and should focus on transforming oppressive and unequal power relationships and structures that are at the root of the conflict itself.

A comprehensive and holistic agenda for transitional justice processes is hard to deliver in practice, and we must take into consideration the economic and political contexts in place. However, we cannot dismiss the important connections between peacebuilding in post-conflict societies and socioeconomic and development issues. Otherwise, we run the risk that victims of direct violence will perpetually suffer from structural injustices, and that promises of a new post-conflict nation will remain only on paper.