by: Shuyuan Shen

“A closed country is a dying country.” — Edna Ferber, American novelist

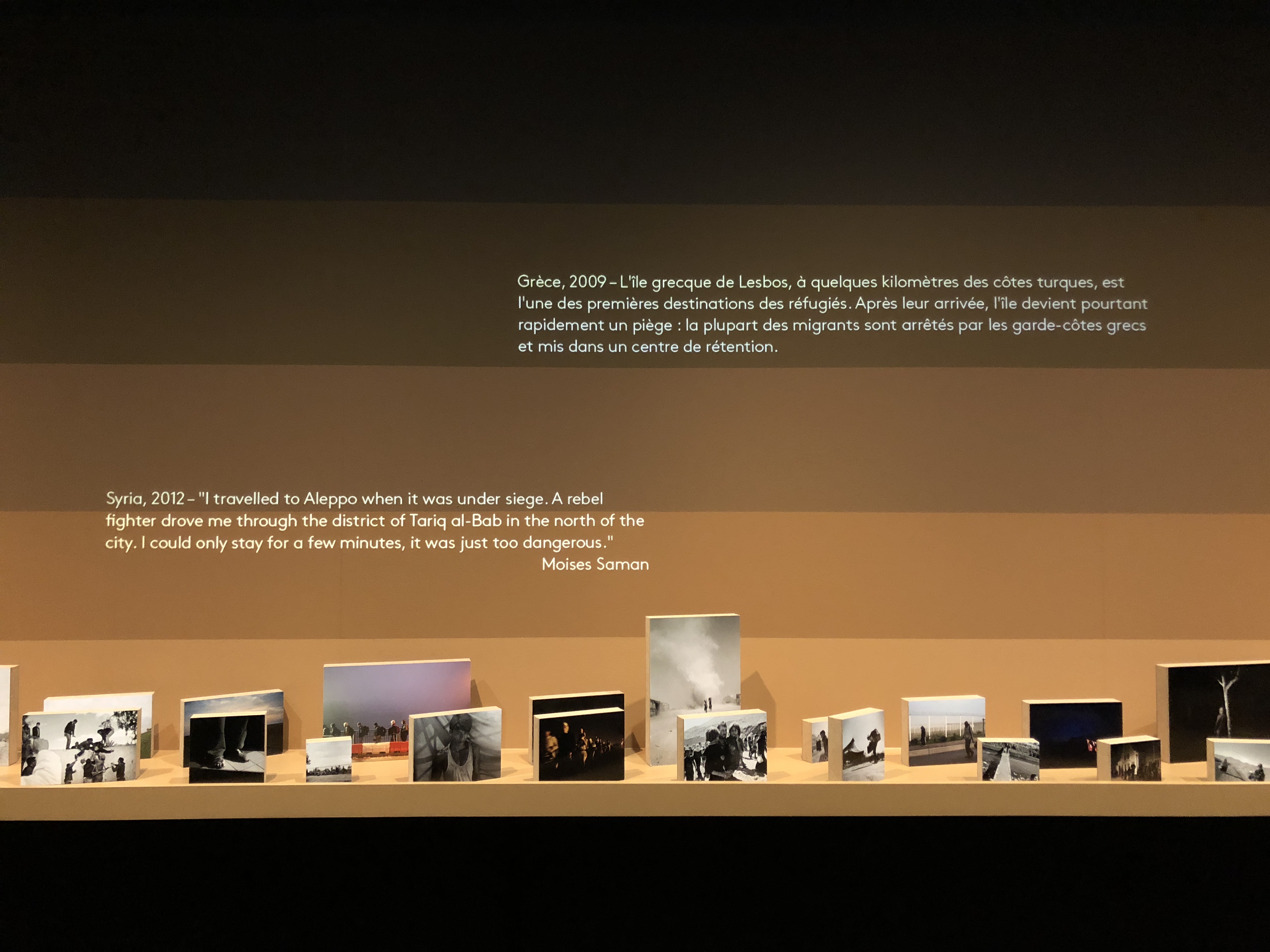

This summer, three Master of Global Affairs classmates and I traveled for eight weeks to investigate immigration enforcement in the United States, Germany, and Greece, partnering with the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops’ Office of Migration and Refugee Services. Unexpectedly while we were in the field, stories of family separation swept through the US. The heartbreaking experience and brutal reality along the US-Mexico border shocked many Americans and stimulated protests across the US to call for more humane border enforcement or even alternatives to enforcement.

IMMIGRATION’S DIFFICULT HISTORY

Many people argue that America has always been a country of immigrants and was built by immigrants. These people do not understand how a country of immigrants could implement seemingly merciless immigration policies, separating children from their parents, prosecuting migrants who do no harm to national security, and deporting people whose entire family and lives are in the US.

To some extent, they are correct. Despite the fact that many countries, such as Argentina, Austria, and France, welcomed large flows of immigrants in history, none of them have developed a collective cultural identity of “nation of immigrants” to the same extent that the US has. People believe in the American Dream that, no matter who you are and where you come from, you can achieve success if you work hard.

However, people who believe in the immigrant ethos of the US often neglect the fact that, although the US is indeed a nation of immigrants, at the same time, it has always been harsh on immigrants. For example, the Chinese Exclusion Act implemented in 1882 prohibited all immigration of Chinese laborers, and the Immigration Act of 1924 restricted migrants from eastern and southern European countries as well as most Asian immigrants. In the 1960s, the civil rights movement exposed the discriminatory and unjust nature of the quota system, which led to the Immigration and Naturalization Act of 1965. Although it terminated the quota system, it was still quite restrictive and maintained the per-country-of-origin limits.

Occasionally, there were pro-immigrant laws and policies carried out thanks to pro-immigrant advocates, and the University of Notre Dame played a significant role in that. Father Theodore Hesburgh, then-President of the University of Notre Dame and former head of the Civil Rights Commission, chaired the Select Commission on Immigration and Refugee Policy (SCIRP) in the late 1970s. The Commission was set up by Public Law 95-412 (passed Oct. 5, 1978) with the mission “to study and evaluate…existing laws, policies, and procedures governing the admission of immigrants and refugees to the United States and to make such administrative and legislative recommendations to the President and to the Congress as are appropriate.” The SCIRP report produced by the Hesburgh Commission helped establish an expansive framework for immigration policymaking, and its central ideas were largely codified in the 1986 and 1990 immigration reforms. Despite some restrictive features, the Immigration Reform Act in 1986 created one of the largest amnesty programs for undocumented immigrants at that time, with a seasonal agricultural program offering legal paths for migrant labors to become permanent residents and citizens, and various protections against discrimination (Tichenor, 2002).

Unfortunately, the pro-immigrant atmosphere changed quickly in the mid-1990s when California’s Proposition 1994 stripped undocumented immigrants of a wide range of social services, including educational benefits for undocumented children. Then, in 2005, Operation Streamline was started, and the Department of Homeland Security and Department of Justice adopted a “zero-tolerance” approach that aimed to prosecute every migrant crossing the US border without authorization. Recently, the family separation scandal broke out, exposing the ignominious immigration policies and enforcement to public scrutiny and criticism.

IMMIGRATION POLICIES: LAGGING BEHIND THE TIMES

The purpose of listing the restrictive immigration laws of the past is not to justify the current administration’s immigration policies. Many of them were implemented when racial discrimination prevailed and universal principles on human rights were not recognized. Sixty years have passed since the adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Many other international or domestic documents that advance the interests of the migrant population have also been established. The rights of migrants and refugees ought to be better protected.

Nevertheless, during our field observation at the US-Mexico border and in Germany and Greece, we questioned our progress since that time. The enhanced border enforcement on the US-Mexico border pushes migrants and asylum seekers to more rugged and dangerous routes. The criminalization of migrants, especially treating illegal re-entry as a felony, punishes those people who have the strongest ties in the US the most, as typically people whose families and social networks are in the US are those willing to risk crossing the border again after deportation. It is the same group that receives the toughest punishment. How could this be just?

In the field, we learned that a grandpa, who was also an undocumented immigrant, was arrested when he was taking his grandchildren to school. Would there be better occasions to arrest him rather than when he was with his grandchildren? We also learned that the Border Patrol adopts a strategy called “dusting” in which a helicopter flies over a group of migrants, raising a dust in the desert and dispersing and disorienting the migrants. Hence, many migrants get lost and die in the desert. There are many more examples of inhumane law enforcement practices like this, casting doubts on the nature of law enforcement.

BUT WHAT SHOULD BE DONE ABOUT MIGRATION?

We still don’t know the answer after our two-month fieldwork. Maybe there is no definite answer to this question. For many people in society, law and order is their most important concern. In their minds, undocumented migrants deserve retribution for their illegal act, and the law enforcement practice on the border is just and well-founded.

Critics of immigration may not reflect on the law itself and debate whether it is just or not. Some may ask how to decide whether certain laws are just or not. To be honest, I don’t know. I am not a legal expert. But I know that, if laws and policies punish humanity and undermine human dignity, there must be something wrong.

One blog post cannot show the complex picture of the whole immigration enforcement system. This is not the intention of this post. Nevertheless, it sheds some light on the restrictive nature of immigration law and the brutal reality on the ground facing migrants.

It is clear to us that, not only is more humanitarian assistance needed, but also more research on immigration laws and enforcement are in great need to protect the rights and interests of migrants in the US and other parts of the world.

My classmates and I will continue to strive to advocate for migration rights and interests. It is our hope that migrants, regardless of their origins and status, can be better protected and their human dignity can be fully respected.

Driving and walking through the arid and vast Sonoran desert in 105-degree heat, helping humanitarian aid workers fill up water tanks for migrant travelers. We encountered “artifacts” left behind by migrants—a child’s shoe, black water jugs, a rosary that now adorns a wooden cross marking the place where the body of a migrant was recently found. We paused at the wooden cross, and let the sun beat down on us, as we took a moment of silence for that loss of life.

Driving and walking through the arid and vast Sonoran desert in 105-degree heat, helping humanitarian aid workers fill up water tanks for migrant travelers. We encountered “artifacts” left behind by migrants—a child’s shoe, black water jugs, a rosary that now adorns a wooden cross marking the place where the body of a migrant was recently found. We paused at the wooden cross, and let the sun beat down on us, as we took a moment of silence for that loss of life.