There are many ways in which in-class instructional time can seem overwhelming, especially to first time teachers. During my first TA experience I remember opening up a word document with the intention of writing up an agenda for the first week’s discussion. I kept staring at the document like it was a vast open prairie, or an empty stage in a sold-out theatre. The time and space I had seemed expansive, full of possibilities and opportunities, but also shapeless and unstructured. In that moment, I found myself wondering: how am I supposed to fill every moment of face-to-face instructional time with meaningful, interesting, and valuable content, and how am I supposed to know after the fact if I’ve succeeded in this goal? In this post, I’ll argue that you can go a long way towards answering these questions for yourself by carefully crafting S.M.A.R.T. learning objectives, and by using these objectives to design and implement daily assessments.

First off, a learning objective is a brief, descriptive statement of one thing that a student will take away from a day’s lesson. They are typically determined by (and fit into) the broader “learning goals” that you set in your syllabus at the beginning of the semester, but are more specific, concrete, and active. Examples include: “By the end of class, each student will be able to distinguish between examples of substances and accidents, and to give an intuitive definition of each.” You might have just one learning objective for a class period, or, if you have more time or if the objectives are less ambitious, you may break it down into two, three, or even more. (For more helpful information on learning objectives, and the difference between a learning objective and a course goal, see this helpful handout. For a taxonomy of different kinds of learning objectives, and how to incorporate these into your course prep see this handout on class prep from the Kaneb Center.)

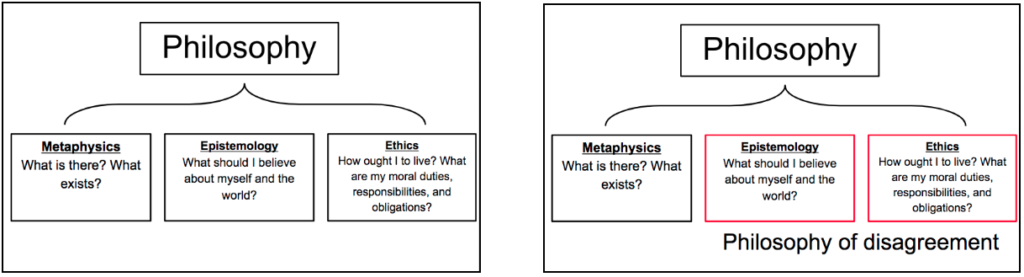

S.M.A.R.T. is an acronym often associated with productive goal-setting in general, and I forget where I even first came across it (see here, here, and here). The acronym stands for Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Results-focused, and Time-bound, and I find these criteria immensely helpful in crafting good learning objectives. I won’t go through detailed descriptions for each criteria (for such descriptions see the links above), but to get an intuitive sense, consider the following two objectives:

- By the end of class students will be able to analyze philosophical texts well.

- By the end of class, students will be able to isolate Singer’s “Obligatory Giving” argument and distinguish its major premises, and give one reason why they agree or disagree with each premise.

Objective 2 is clearly better along each of our five dimensions.

S.M.A.R.T. objectives can help structure in-class time in at least two ways. First, they can help you determine what information you need to present and what sorts of activities you need to have your students engage in, and what to prioritize in the distribution of class time for any given meeting. If objective 2 was one of your objectives, for instance, you’d need to make sure to leave time for the students to read and mark-up a paragraph of text (3-5 minutes), share their thoughts with a neighbor (2-4 minutes), and collaborate on reconstructing the argument as a group (5-8 minutes). If you have three or four other objectives for that day, you might think about simplifying the task, or about giving them a little more help along the way.

The second way S.M.A.R.T. objectives can help you structure in-class time is in a more global, semester-level sense. S.M.A.R.T. objectives — if crafted well — naturally give rise to concrete assessment mechanisms (they are, after all, Measurable, Results-focused, and Time-bound). To expand upon our example: you could ask your students to write down the premises and conclusion of Singer’s argument on a half-sheet of paper and turn it in. If pressed for time, you could cold call on three students and ask each to offer a premise and a brief reason to agree or disagree with it. If the objective and content are crucial to the course as a whole, and directly related to your overall learning goals, you might hand out a worksheet at the end of class, or have students take an online quiz to ensure that they’ve attained proficiency. This feedback is an invaluable resource in helping you to determine where to spend valuable future class time.

As college instructors, we get precious little face-to-face instructional time with our students, so it’s important that we structure the time we have effectively. S.M.A.R.T. learning objectives can help us to do that, and in a way that isn’t overwhelming or overly time consuming. Moreover, I’ve found that pairing my objectives with daily assessment mechanisms, and even using the process of designing such mechanisms to clarify and evaluate these objectives, allows me to foster a more “communicative” classroom experience; i.e. one in which I’m getting feedback from the students that I can use to create future objective-based learning goals that are responsive to their needs.

Links and citations:

“Goals vs Objectives.” University of Iowa Information Technology Services, Office of Teaching, Learning, and Technology. N.p., n.d. Web. 9 Dec. 2017. https://teach.its.uiowa.edu/sites/teach.its.uiowa.edu/files/docs/docs/Goals_vs_Objectives_ed.pdf

“Articulating Learning Goals: A Path to Increased Efficiency and Improved Student Performance.” University of Notre Dame, Kaneb Center for Teaching and Learning. N.p., n.d. Web. 9 Dec. 2017. http://kaneb.nd.edu/assets/75457/learninggoalsho.pdf

Image source: http://habitica.wikia.com/wiki/SMART_Goal_Setting