by: Jamie McClung

Bangladesh Field Sites: Communication without Words

Jamie McClung is currently working on a project with Bangladesh Centre for Advanced Studies for her Master of Global Affairs i-Lab experience, focusing on women’s adaptive capacity to climate change, particularly in rural Bangladesh. She and her partner, Chista Keramati, have just completed their first field site visit to Teknaf, in the southeast corner of Bangladesh.

It’s quite difficult to write a small blog post to describe a trip to another universe. In a few words, I’m meant to describe the surprising findings, the warmth of the people, the strange geography, the never-ending questions in my head, but how? Instead, I’ll highlight 5 aspects of our trip that were particularly meaningful or interesting to me, each accompanied by a picture.

1) Presents, but Little Presence:

One of the very first things I noticed was the overwhelming presence of NGOs in Teknaf—presence in terms of goods, like these UNICEF backpacks, but not in terms of people. Yes, we saw endless Land Rovers associated with different organizations on the road, but I was surprised by the lack of interaction between the people in these vehicles and the local people. I became curious about what these NGOs were doing in and around Teknaf, and if they ever stepped out of the Land Rovers. Some of my questions were answered when we met with UN Women later in the week, and I realized that they share similar goals for integral human development as we do here at the Keough School.

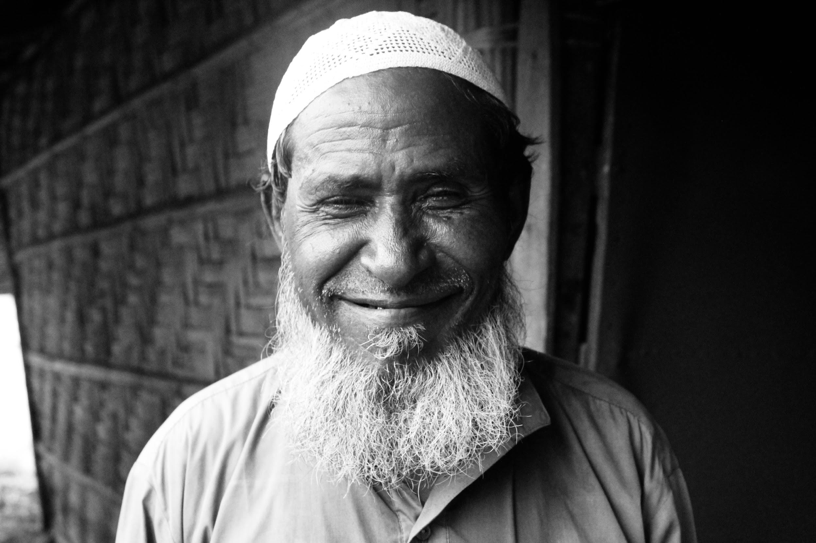

2) Communication without Words:

We talked with this elderly man on our first day in the village, and saw him again on the second day. He showed me that you can make a friend and communicate without any words at all. This continued to happen throughout the week, through shared smiles, laughs, and simple eye contact that conveyed a curiosity about one another and an openness to learn more. I experienced these small interactions both during focus group discussions (FGDs) and during our walks around the villages.

3) Water, Water, Everywhere:

This first field visit made it beyond clear why Bangladesh is so extremely vulnerable to climate change and rising sea waters. One of my thoughts when returning to Dhaka from the field was that maybe Bangladesh was the last country God created, and He just had a bit of land left, so He spread it out as much as He could, took His chances, and let water inhabit most of the space. It is low-lying, marshy, and a land covered in rivers.

4) There’s No Average Bangladeshi:

To harken back to a comment I made during one of my first semesters at the Keough School of Global Affairs, I truly believe that there is no such thing as an “average” citizen of any country. This little girl, and the indigenous Buddhist Rakhine village we visited on the last day of our visit to Cox’s Bazar, reaffirmed that belief. This indigenous community had their own language, their own religious leader, and their own way of life that was extremely different than what we had experienced in the days before that.

5) Geographic Vulnerability Can Be Overcome:

The final insight I had during our first field site visit was that local knowledge is already being used for adaptation, without any assistance from the outside world. This indigenous, Buddhist village has always built two-story homes with an open ground floor. It allows them to have a safe place in their home when it floods. This kind of evidence gives me hope after a week of seeing small homes built directly on the ground, unable to protect families during floods or cyclones.

All in all, it was a positive week. There were times I was frustrated at how much families were struggling to survive, and how clearly the land left them vulnerable, but I was also awed by the resilience and hospitality I saw when interacting with the rural communities here. Despite being labeled as “vulnerable” by their national government and international organizations, these communities have survived and they continue to live life with or without us. This realization led me to another: development isn’t about helping people survive; it’s about accompanying them as they attempt to thrive. Now that we’re back in the smog of Dhaka, Chista and I are both counting down the days to our next field sites where we hope to continue bonding with and learning from the local communities we visit.