by: Seiko Kanda

“Me regalas un pan con ave-palta, por favor?”

“Give me a chicken-avocado sandwich, please?”

It was my morning routine to buy this typical Chilean sandwich from a kind, elderly lady in a tiny mom-and-pop store. The happiness that 1,200 pesos ($1.70) bought me on my way to the Enseña Chile office did not simply come from the nourishment the sandwich provided, but from the daily interactions with the shopkeeper that made me feel like a local.

Chewing off a piece of firm bread on a chilly winter morning, I sometimes found myself wondering how a decade could turn a Japanese high school student—who was interested in little else other than playing soccer—into someone standing on exactly the other side of the earth, spending his summer days thinking about the high school students of this long, beautiful country in South America?

STUDYING HOW SCHOOLS IMPROVE

Enseña Chile, a non-profit promoting access to high-quality education for all children, works to address many of the challenges facing the Chilean education system today. Chile’s market-oriented educational system, formed by its military government in the 1980s, has contributed to an inequality of educational opportunities among the country’s youth. According to an OECD report from 2017, Chile had the fifth-strongest association between socioeconomic status and student performance among all 72 PISA (OECD Programme for International Student Assessment) participating countries.

Colegios Que Aprenden (“Schools That Learn”), a consulting branch of Enseña Chile, believes that school leaders who pursue the higher academic performance of students are falling into a common pitfall. While underperforming schools are concerned about the academic results of students, their efforts to increase students’ standardized test scores often turn out to be ineffective because the school communities do not have a cultural environment that supports students’ academic success. Colegios Que Aprenden encourages these school leaders to invest in creating better school cultures (e.g. implementing effective feedback loops in schools, sharing common ideas about teaching, facilitating the professional development of teachers), which serve to bring about greater academic achievement among the students.

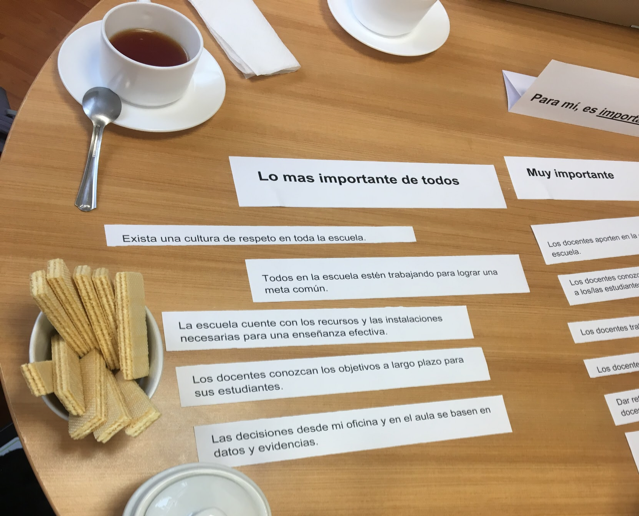

Partnering with Colegios Que Aprenden, our i-Lab research project visited a number of struggling Chilean public schools. Mukhlisa, Frank, and I interviewed multiple school leaders and teachers to identify how they prioritize different ideas for school improvement.

While we learned in one of our MGA classes last semester there were theoretical “primordial elements” of school improvement established by researchers in the United States, we still had the following questions: To what extent was this research on school improvement applicable in the Chilean context? More specifically, how might the findings of this research compare with what we would find by asking individual school leaders and teachers what they think would enable them to reach their goals as educators?

Our findings from over thirty interviews we conducted with school stakeholders revealed that both teachers and school leaders in Chile tend to value a close relationship between three elements—a culture of respect, collaboration among teachers, and shared common visions. Our data indicate that the specific strategies for school improvement are better implemented when the school employees feel respected and when they possess a shared vision through actual experience of collaborative activities.

SCHOOL AS A SUPPORTIVE LEARNING COMMUNITY

Colegios Que Aprenden encourages all employees within an educational institution to learn continuously. A school that learns calls its members to build a culture of respect, to collaborate better and to share a significant objective as a school. A culture that promotes learning among all its members is what enables everyone in the community to continue maturing.

One afternoon, I had the opportunity to stand in two K-10 classrooms in a school on the outskirts of Santiago. While leading a class on Japanese history, I reflected on how crucial it must be for teachers to feel supported and cared for by school leaders—or more precisely, by the school culture—in order to be able to fully engage in their students’ lives. Teachers can support students only when they themselves experience similar support from others around them. This may sound banal and idealistic, but considering its potential for positive impact on each student’s life, it ought to be pursued by all educators.

As the project went on, I recalled my past experiences in which teachers in my life (including my family and friends) accompanied me and how they personally cared for and encouraged me to grow, forming me to become who I am today. It has been the countless encounters with people whom I respect and by whom I feel respected that has brought about the change that the soccer-loving Japanese high school student experienced over the past decade. Each person who has cared for me—directly or indirectly—has opened doors to new discoveries and new steps in my life.

These faces that I recall are also individuals who need to be respected and supported. We all need to belong to a learning community in which members respect one another—and support one another—in order to be able to learn and to grow. This objective to build a learning community is radically process-oriented, and it is crucial for any educational organization to attain its goals.