Dear Daughter/Son,

Let me tell you about the time I spent in Greece during my master’s degree fieldwork. It is the month of July and the year is 2018. It’s 34 degrees Celsius outside, but the room must be a few degrees warmer since there is only a tiny portable fan on the desk and the open window fails to provide much ventilation.

Imagine me sitting on an uncomfortable chair with a few months-old baby in my arms. The child is agitated maybe because he/she is hungry or feeling hot or both. I try to pacify him/her. Imagine this baby is you. The air feels thick and I try to ignore the sweat. However, this woman is not me. Instead, I sit in the opposite chair facing her.

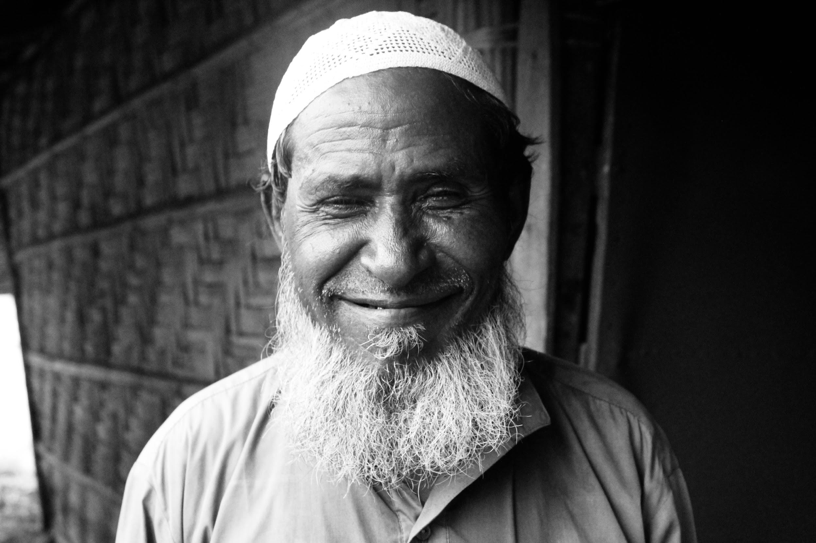

I could be this woman easily. We are from the same country, same city and almost the same age. So I could be the one in that chair with that baby in my arms, forced thousands of miles away from home. She does not like me at first—her face is hardened, and she makes no attempt to conceal how unwilling she is to talk to me. To her, I am just another person who wants to hear her story and not offer her any help or benefit in return.

Yet as I explain our project to her and tell her that I cannot really offer or promise anything in return other than listening to her and telling her story, she opens up to me. The system has failed her and thousands of people like her. People are in limbo, as if their lives have been paused while they are stuck in Greece trying to find a safe space for themselves or trying to build a better life. Some are lucky to be able to apply for asylum and get accommodation. The rest, however, struggle to be able to register even. They sleep on the streets.

There are so many things I want to tell you that I have seen. I wish I could show you, but I do not wish for you to be here. I get a tiny glimpse into the life that the migrants are living here due to my hijab. When I walk the streets or board a local bus, people think I am a migrant too. When they see me, they stare. When they see me with my American colleague, they stare. The other day on the island of Lesvos, as I sat alone working on my laptop at a coffee shop a few feet from the Aegean Sea, three old Greek women walking by stopped near my table and commented about me while almost pointing at me. I am assuming a migrant sitting at a coffee shop with an expensive-looking laptop puzzled them. All this staring was amusing at first, but it soon became annoying. I now know what it feels like to be an ‘outsider’ and what it means when people say that situations between locals and migrants are sometimes tense.

I tell this to you so that you know that this world is a strange place. There is so much pain and unfairness. Despite all that we had been taught in our Voices from the Field sessions in i-Lab, nothing could have prepared me for this, but those sessions did help me cope when I did not know how to process things that I am seeing here. On the other hand, there is also a lot of good in this world—people full of compassion, kindness and hope. I have come across many of them here. I am constantly amazed by the resilience of these people on the move and those helping them. In the most hopeless of circumstances, they are persevering. Know that you must be in this latter part of the world.

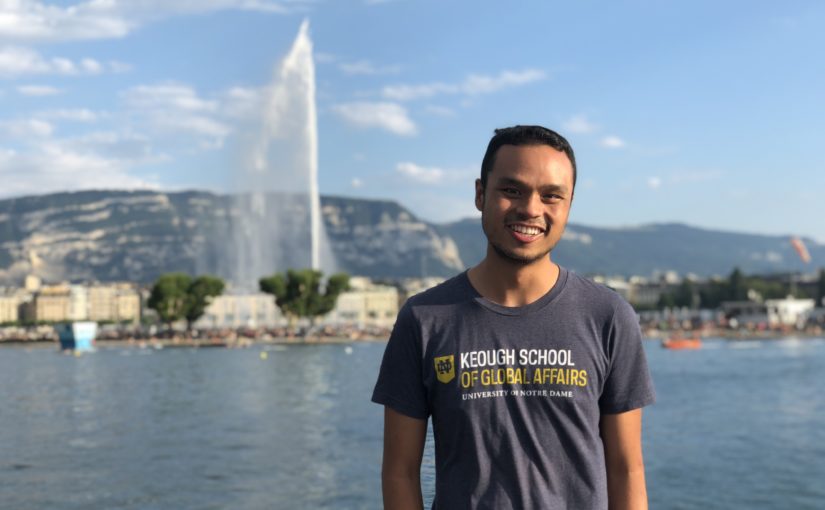

Being part of the Master of Global Affairs has put me in a unique position. This summer project, part of the Integration Lab at the Keough School, has given me the opportunity that very few have. This world is complicated, which explains why people can justify keeping more than 7,000 migrants in a place like Moria camp under terrible conditions. But I am trying to learn at The Keough School how to start a conversation about this and eventually change this complicated international system that we have created. If there is one thing I want you to know, it is that complicated and flawed systems do not need to be accepted just because they have existed for so long. Instead, they need to be changed.

Yours lovingly,

Your mother Mehak

The

The