As a student in the Keough School’s Master of Global Affairs program, I genuinely appreciate the diversity of my cohort: their nationalities and cultures, their personalities and perspectives on issues such as religion, freedom, development, peace, justice, and social responsibility. Both in class and out, numerous opportunities exist to dive deep into the “whys” lying beneath each individual’s theories and understandings. These engaging interactions have been instrumental in helping me to learn how to seek out the contextual meanings behind the research during my Integration Lab global partner experience.

Partnering with Catholic Relief Services’ Emergency Response and Recovery Department through the Keough School of Global Affairs’ Integration Lab, my team is researching opportunities to advance financial inclusion with forcibly displaced populations and host communities, specifically by looking at humanitarian cash transfers. To better understand the lives of refugees, transnational migrants, and those who live where these groups settle, we are spending one month in Bangladesh engaging with those affected by the Rohingya refugee crisis, and one month in Uganda examining the same data points with South Sudanese refugees and locals in and around the Bidi Bidi refugee settlement.

The complexities encompassing the situation in Bangladesh require a similar deep dive, looking at the “hows” and “whys,” which in turn will drive the search for solutions. We are speaking with those who live out their daily lives surrounded by humanitarian aid organizations, food aid trucks, and those who are forced to engage in the scramble for resources such as water, land, and employment. In both refugee and host community populations, a multidimensional problem unfolds which includes layers of governmental policies, social status, goods and services markets, and corruption. The context of these dimensions is key to our understanding and to finding pathways forward for the beneficiaries of humanitarian assistance.

The topic of cash assistance is foremost on our radar as we investigate its potential to advance the well-being of those in crisis. In the realm of international development, cash has become the preferred method of assistance, though in-kind goods distribution is still far more heavily utilized. Cash assistance allows those in need to prioritize their own needs and allocate the funds to that which most greatly benefits their family.

Outside development circles, I often hear criticisms that giving cash leads to misuse of funds and the directing of funds toward luxury or illegal goods. However, this is not substantiated through research. Check out this video, “10 Things You Should Know About Cash Transfers,” which does an excellent job of explaining the benefits and dispelling the myths of cash assistance.

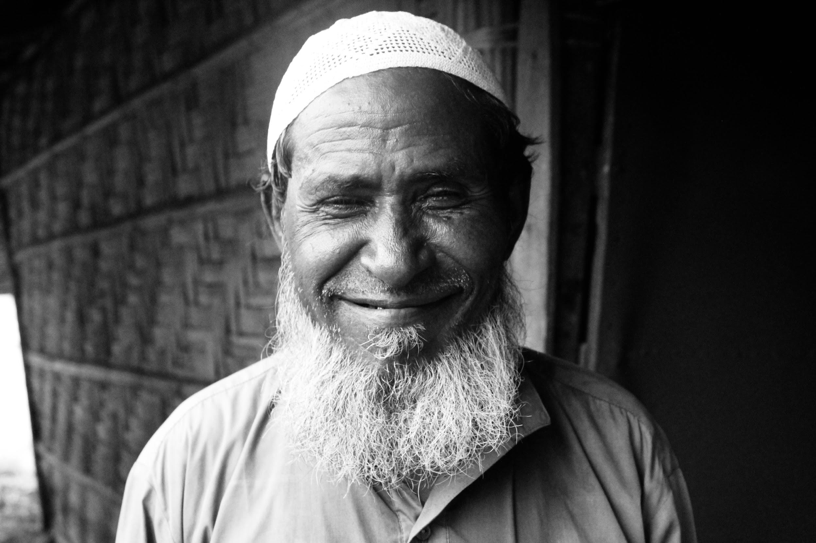

VOICES OF REFUGEE COMMUNITIES: BANGLADESH

As we sit and listen with those people who are in most need, I am a student to their teachings. They give their opinions to us honestly and offer insightful solutions.

Focus group discussions with host community members and with Rohingya populations give a community perspective to our research. Likewise, our individual interviews allow us to get to know the effects of the crisis on a personal level with business men and women, homemakers, and those simply struggling to survive. For example, one woman, who happened to be a widow, spoke of her hopes for the futures of her four daughters, her desire to provide them a good education, and for them to find good husbands. These motivations for her financial decisions would have remained a mystery to us had we not taken the time to get to know her.

Being welcomed into their homes, sharing a cup of tea and a biscuit, and then asking about their personal finances seemed awkward and intrusive at first. I quickly developed a sense of respect for the participants’ openness and humility and realized it was not only important for me to hear their stories but equally important for them to be able to share them. There is a beauty in that exchange that is sometimes joyful and sometimes wrought with emotional pain, but it is in these freely offered discussions where we find the fundamental reasons for the choices we make.

VOICES OF REFUGEE COMMUNITIES: UGANDA

As we continue to contemplate the data gathered and the interactions experienced with the Bangladeshi people and the forcibly displaced Rohingya groups, we are quickly moving forward in learning about the daily life and financial needs of refugees in East Africa. The thinking behind the policies demonstrates a state of reciprocity that is apparent in developing nations in Africa, specifically in the social cohesion of community members. Relying on family and friends as a network of support is a must where state social safety nets are not common. This is how I see Uganda welcoming the refugee; welcoming them as neighbors and facilitating their integration into a functioning community and economy and remembering how, in the recent past, Ugandans also sought refuge in neighboring countries in times of crisis.

WHY CONTEXT MATTERS

The varied responses to the refugee crisis in Bangladesh and Uganda are different not only because of local cultural practices or because of religious factors, but also because context matters. Histories matter, resources matter, belief systems matter, and the hopes and dreams of the displaced matter. Similarly, when thinking of cash interventions and how to best support these and other populations affected by humanitarian emergency situations, context is of the utmost importance. Building relationships of trust and diving deep into the mindsets of those affected can enlighten our thinking and inspire true solutions.