by: Max Ngoc Nguyen

In February Greg Van Kirk, founder of Community Empowerment Solutions (CES) and an Ashoka Fellow, approached our Keough School i-Lab team and proposed an intriguing research question: NGOs tend to work in silos, thus miss out on potential collective outcomes as a result. Could our team work with CES in designing a platform that would encourage NGOs to collaborate with other organizations in order to maximize social impact? As we have begun to dive deeper into this project, we have learned fascinating things from the 54 organizations we have interviewed.

1. Organizations collaborate better than we expected

Before heading to our fieldwork in Guatemala and Ecuador, where CES has a strong presence, we spent two months in the classroom conducting research on why most NGOs do not collaborate with one another. We spoke to experts, examined academic literature, and perused articles on SSIR. We came up with a plethora of reasons: nonprofits compete for the same funding, NGO employees are too busy, organizations are not interested. Basically, we started with the assumption that there is little collaboration in the NGO sector.

During the course of our interviews, we learned that organizations are collaborating more actively than our research suggested, at least in Guatemala and Ecuador. In fact, 83% of the interviewed NGOs exhibit dynamic patterns of either working with or looking to work with others. One executive director from an education NGO in Antigua, Guatemala, summed up this sentiment best:

“We’re always looking for partnership. In fact, I believe that creating and promoting partnerships with a lot of NGOs that have affinity [with us] is the only way we’re going to make an impact.”

2. Organizations that look beyond their field of specialty tend to seek more alliances

We have noticed an interesting correlation: NGOs that express the desire to offer services beyond their areas of expertise are more likely to reach out to others. As an example, in Lake Atitlán, Guatemala, we came across a social enterprise that specializes in exporting artisan products to the United States. They also want to improve the health conditions of their employees, but they do not have skills in that field. Thus, according to the Development Manager, they partnered up with others:

“We have a health-based initiative, such as sexual health family planning. But we’re not a health-based organization. So we collaborate with organizations with specialty in health-based education. They can provide us with tools, resources, or modules for education. In return, we provide access to communities.”

3. The greatest challenge to collaboration is different priorities

The aforementioned challenges that we researched in class are indeed echoed by some NGOs, but 35% of the interviewees believe the biggest obstacle to collaboration is conflicting priorities. In Cuenca, Ecuador, a nonprofit focused on technical training for farmers told us that they would only work with groups that offer complimentary services to theirs. If you want to make clean water, build schools, or construct a soccer field, for example, they are just not that into you.

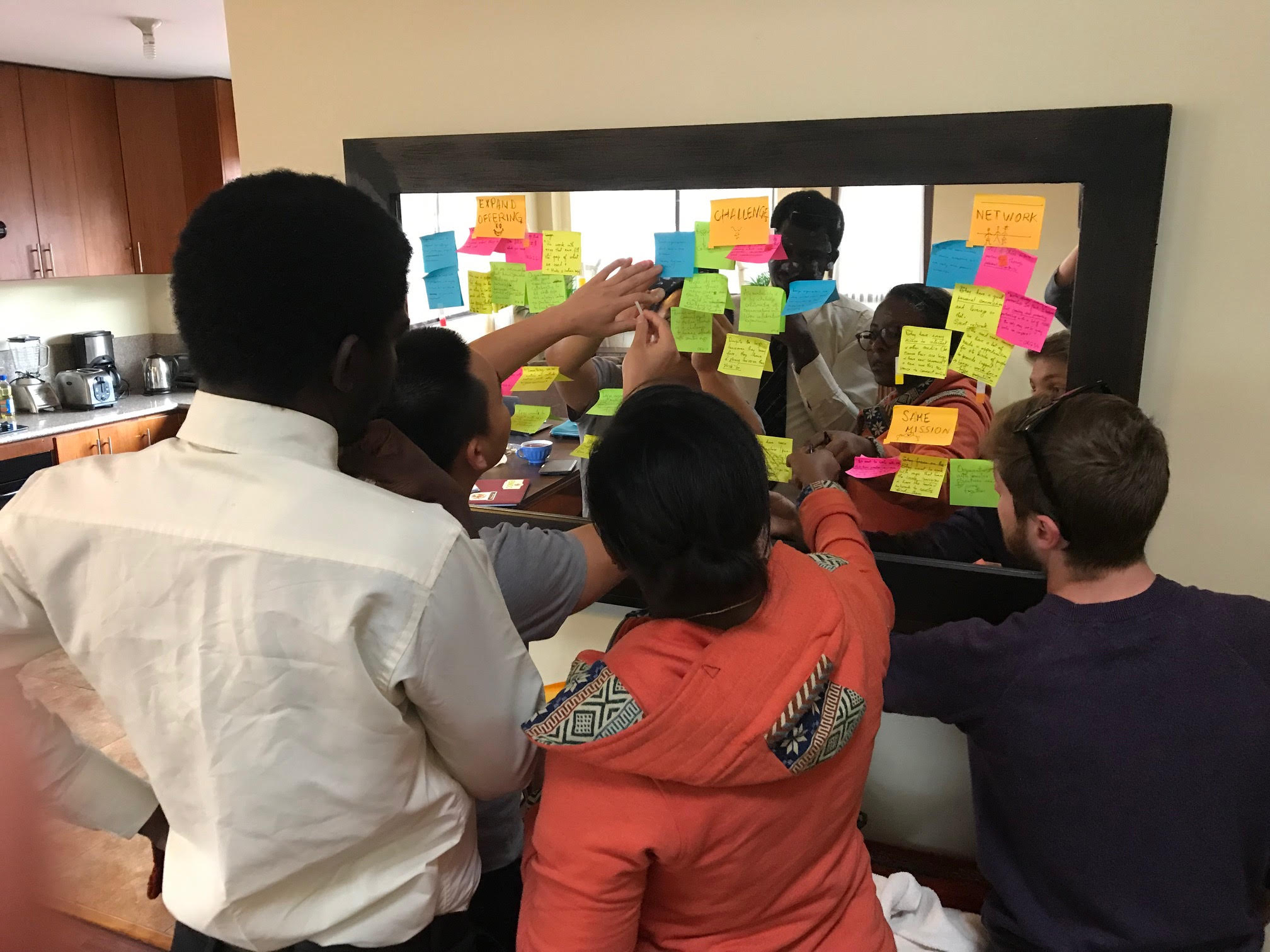

4. Capacity-building workshops are key to creating partnerships

An overwhelming 77% of organizations have claimed that they initiate collaboration because they have a friend who works for another NGO, met a potential partner at a fair, or even bumped into someone at a bar. From these observations, we have concluded that in order for alliance-building to flourish, we need to make these coincidental meetings happen more frequently and systematically.

We have discovered that one of the best ways to do so is through organizing training workshops on various topics. Staffers and leaders from different NGOs come to these events to acquire knowledge in fundraising, navigating social media, and managing foreign volunteers. Whatever the theme is, participants get to know one another, exchange contacts, and build personal connections. Afterwards, they start to collaborate with one another.

In conclusion, NGOs are indeed working together more often than we anticipated. But these partnerships take place organically. We believe the platform we are designing for CES will help these collaborations occur on a systematic scale. Most important of all, it will incorporate the personal connections necessary to spark enduring alliances among NGOs.