I want to start by saying how much I appreciated my time in Bosnia. I gained a new level of insight into the culture and social problem facing the Bosnian people, and with that I have gained a new level of empathy. So, I found this experience to be deeply satisfying on both a personal and academic level. As part of this new insight, I developed a deep appreciation for the complexity of the language. Having not been exposed to the Bosnian/Serbo/Croatian language in any kind of formal setting, I had no idea how complex the language actually is. The Structure is such that it makes use of 7 cases, and the endings on of adjectives, verbs, and nouns must all transform depending on the case. Having no equivalent in English, this was a concept that remains very difficult for me to grasp. It also means that though you may understand every word in its infinitive, the act of transforming the constituent parts of the sentence renders its final form unintelligible. The net result is that, while I believe I have made mch more progress than would have been possible without an immersion program, I did not achieve the level of proficiency that I had hoped. That said, I do believe that I know have a foundation that will enable future study and that will equip me with the necessary skills to continue my studies without access to formal classes.

In terms of personal development, the summer was a profoundly eye-opening experience for me. Although it have spent a few months in Bosnia as part of a non-linguistically focused study abroad program the structure of that program prohibited me from engaging with the culture in a deep way. I was there with other American students, being taught in English, and we would hang out together then go back to our hotel at night This meant that though we were in Bosnia, I never as though I were actually experiencing the culture. This summer, in addition to daily intensive language classes, I also received peer tutoring and lived with a host family. This enabled me to truly understand the critical role that family plays in this culture. Nearly everything is centered around familial experiences and children generally live with their parents until they marry. After marriage some even live on a different floor of a family house or in close proximity to their family. This type of communal mentality emphasizes the collective rather than the individual, and provides a very different understanding of the role and important of the personal. While this can undoubtedly be a beautiful thing, there were also many times that I found this dynamic challenging. A primary reason is that this norm of community is accompanied by very strong gender norms that can be difficult to accept. As a result I came away from this experience with a renewed sense of gratitude for the relative progress that has been made around gender equality in the US.

The experience of chaffing against gender norms provides that basis for the most important piece of advice that was given to be before I left: be flexible. While that can be a hard ideal to maintain in a foreign context, I have found it essential to remember that what makes foreign travel so compelling that you learn a great deal about yourself when outside of your normal comfort zone.

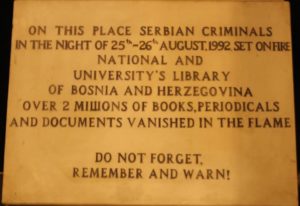

It is hard for me to overstate the benefits that I have derived from the SLA grant. Without it I would not have been able to spend a prolong amount of time in the region, and as a site for future research this will be critical to the long-term acquisition of my PhD. My dissertation question focuses on the way states use monuments to craft narratives of conflict in the absence of total victory. My experience this summer has given me greater insight into the location and function of monuments in Bosnia. It has also ensured that, while nowhere near fluent, I possess enough knowledge of the language to be able to read many of the inscription prominent on the monuments. This is critical because the function of monuments is often emblazed on the material structure. This program has therefore been critical to development as a scholar and human being. Thank you for this incredible opportunity!