When I first started sharing with my colleagues and community that I would be living in El Salvador working with ex-gang members, their first question was “Will you be safe?” This question was admittedly ironic, since my placement was with Creative Associate International’s Crime and Violence Prevention Project (CVPP). While the question was rooted in concern for my well-being, it reflects the ways in which the discourse around El Salvador is dominated by violence, gangs, and poverty.

At the Keough School of Global Affairs, many of our classes demand interrogation of themes like this. In contexts of violence such as those in El Salvador, there has been a tendency to rely on repressive tactics that risk exacerbating the problem. There are an estimated 60,000-70,000 active gang members in El Salvador. If each of those gang members is part of a family who could be affected by repression, then there is tremendous risk for creating more division in the larger society rather than addressing the original conflict.

The CVPP is one of the first large projects to work on tertiary prevention, which is direct intervention with people looking to leave gangs. Focusing on rehabilitation of people trying to leave the gangs—already very challenging—creates opportunities to lower the number of gang members, decrease violence, and address original factors that lead to people joining gangs. Out of most of the ex-gang members I have spoken with, many reference wanting to feel like their identity is respected and that their well-being sustained. Due to contexts of unresolved conflict, scarce resources, classism and other issues that maintain violence, people who join the gangs seek alternative groups that respect their human dignity.

For example, there are two dominant gangs in El Salvador, both of which originated in Los Angeles in the 1980s and 90s. During these years, a surge of Central American immigrants fleeing civil war and conflict landed in LA seeking refuge. LA did not have the infrastructure to support the sudden influx of people, which resulted in high unemployment and dense urban living situations. Existing gang violence and insufficient municipal infrastructure created an impossible reality, which led to the creation of new gangs for safety and community reasons. With high homicide rates and violence in LA, the US responded with heavy-handed incarceration and deportation policies. This response sent young men back to their birth countries, though many did not even speak Spanish. The policy implementation could not have foreseen the violence that the US would export back to Central America, which in 20 years would create a new iteration of the immigration crisis.

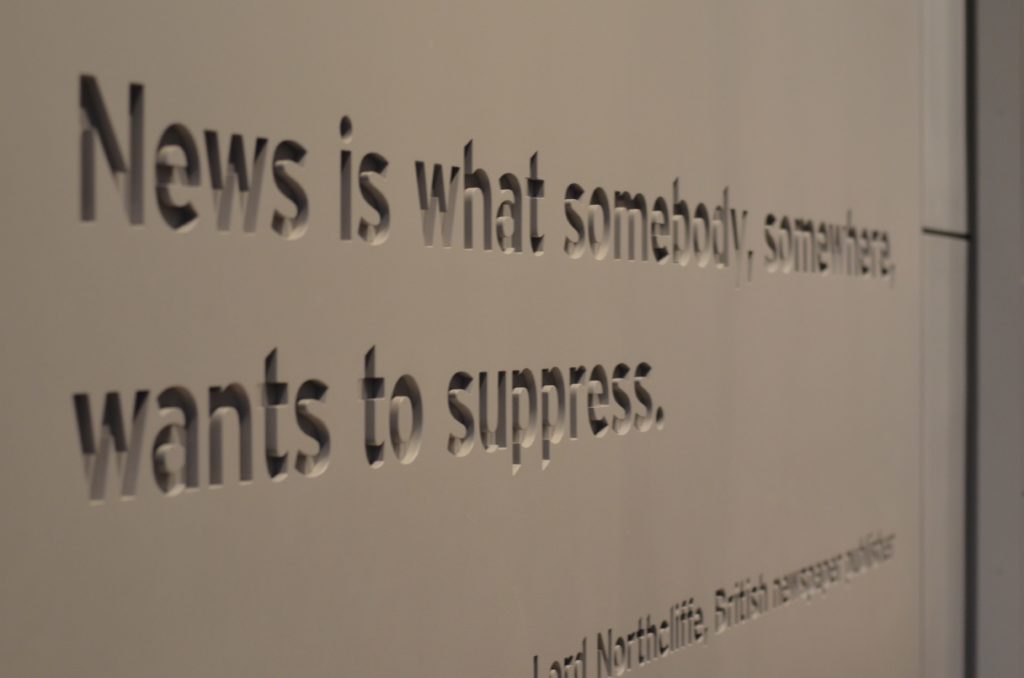

For the last 10 years or so, the popular rhetoric assigned to gangs and gang members in Central America has been one based on violence and fear. The violence perpetuated by gangs is harsh and inexcusable, leaving several communities in El Salvador struggling. Through extortion and other forms of violence, the gangs in El Salvador pose threats to the Salvadoran social fabric that increase instability, migration, and lower chances of success. With every new iteration of repressive mano dura, or Iron Fist policy, gangs adopt a more formal infrastructure and presence.

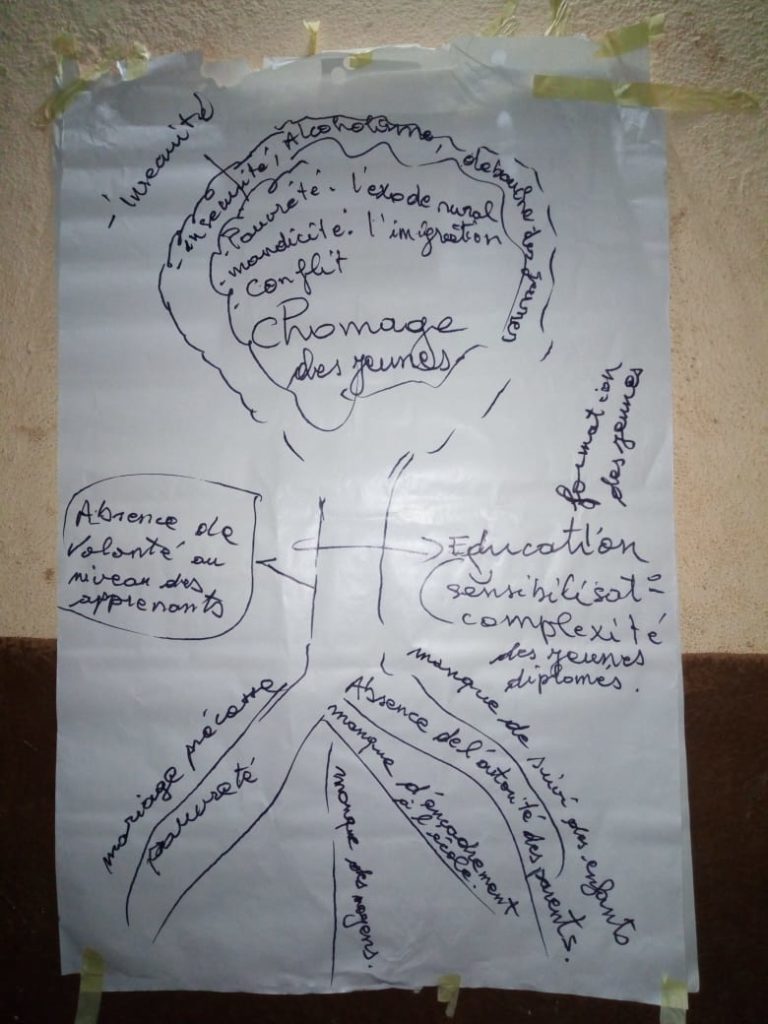

Gang members may commit violent acts, but the questions need to be asked in order to think about gangs origin and historical trajectory. Why did they end up in a gang in the first place? How did the public institutions, international policies, and social fabric fail people enough that they would join a gang? How do gangs provide a sense of safety or security to involved people that they may not feel otherwise? Applying an anthropological lens reveals more answers that may not excuse behavior, but offer hints for disrupting and transforming violence.

As a peacebuilder from the USA, I come home every day with new questions, information and experiences to think about. My country not only deported the original gangsters, but also policies that provide quick answers without addressing root causes. Scholar-activist John Paul Lederach’s reflections resound daily: “To speak well and listen carefully is no easy task at times of high emotions and deep conflict. People’s very identity is under threat.” The starting question may still be, “Will you be safe?” But as practitioners, we must reframe the question to “How is this person not safe due to underlying structural and historical causes that threaten the dignity of the person in front of me?” If practitioners do not, we risk replicating historical patterns of violence towards current and future generations, compounding the root causes and contributing to future insecurity.

The

The