By: Audrey Thill

It takes four types of people to change the world–rebels, organizers, helpers, and advocates–at least according to scholar activists George Lakey and Bill Moyer. When applied to the climate movement, you might readily think of the rebels and organizers. These are people marching or blocking bulldozers, children boycotting school to demand more action, and frontline communities mobilizing to defend their land, forests, water, and lives.

When I tell people I’m studying global affairs at the Keough School of Global Affairs, they think I’m training to be a mediator who brokers major peace deals. While there may be some among my inspiring classmates who do just that, I identify more as an analyst-advocate hybrid. I prefer to work behind the scenes, analyzing issues and identifying points of connection between parties. I tend also to focus on conflicts that involve Earth, climate change, and environmental justice. Thanks to the flexibility of the Master of Global Affairs program, I’ve been able to tailor my classes, projects, and now my internship to focus on my interests.

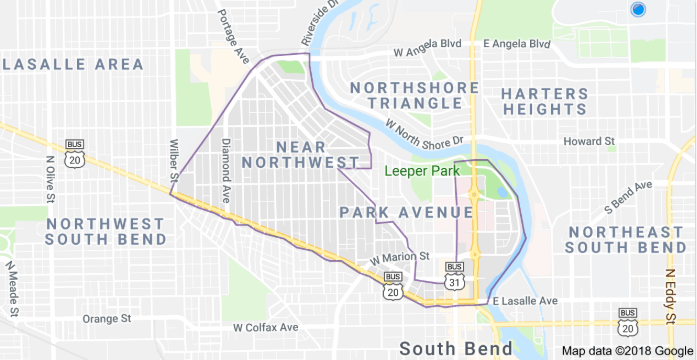

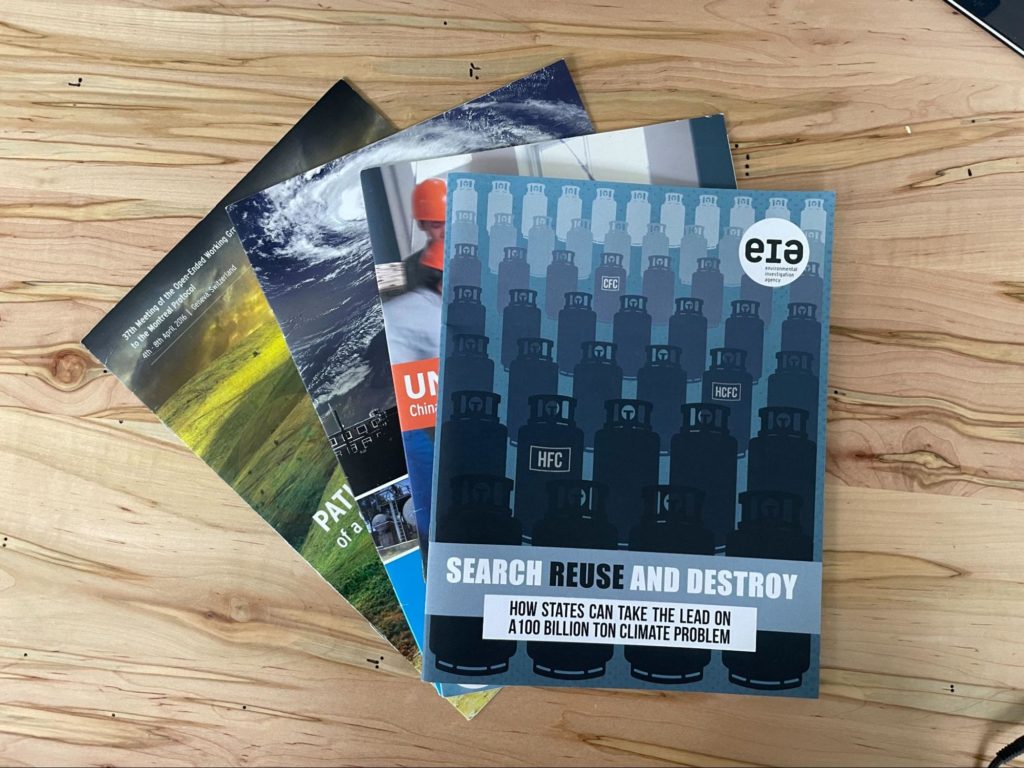

Currently, I’m based in Washington, DC, working as a climate intern for the Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA). EIA is a nonprofit organization that engages in strategic, alliance-based campaigning to protect forests, wildlife, and the climate. They conduct undercover investigations, support local environmental groups, and advocate for greater transparency from governments and corporate actors. I love the diversity of approaches they use to tackle these complex issues. For example, sometimes they release hard-hitting reports, while other times they collaborate with partners behind the scenes to advance their climate campaign goals.

EIA’s climate team focuses on hydrochlorofluorocarbons, chlorofluorocarbons, and hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs). Say that ten times fast. In simpler terms, these are chemicals used in HVAC, refrigeration, and manufacturing of goods, for example, non-stick frying pans. Many of them are also super-potent greenhouse gases. Currently, the climate team is monitoring US implementation of its commitments to phase down ozone-depleting substances and other fluorinated gases that contribute to climate change.

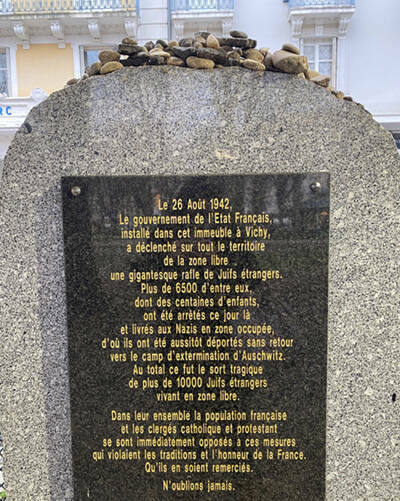

So far in my role at EIA, I’ve conducted research to inform undercover investigations, edited and fact-checked policy reports, and drafted a blog on the intersections of climate change, chemical emissions, and environmental justice. I’ve also enjoyed observing how this small team contributes to state and national climate policy issues, from curbing the illegal trade of refrigerants to raising the alarm about the global uptick in uncontrolled chemical emissions that are driving climate change and contaminating water and soil. Most exciting of all was to see more than ten years of their work pay off in a bi-partisan congressional vote to ratify the Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol, an international agreement that aims to rid the world of climate-polluting HFCs. It was a promising summer for US climate policy, but there is much more to be done.

If you’ve never thought about fluorinated chemicals, you’re not alone. This is an obscure topic for the average person despite the fact that our supermarkets and industries are leaking gases that are hundreds to thousands of times more potent than carbon dioxide. With effects this serious, use and regulation of fluorinated chemicals really should be everyone’s business.

Which brings me back to my point about the four types of people to change the world–it is undeniable that protests are an effective tool to build collective power and demand change from power holders. After street protests wane, however, we need actors like EIA who dive into the details and work in the background, ensuring that those same power holders stick to their promises. I’m thankful for this opportunity to learn from EIA and their long-term commitment to translate technical topics into policy solutions and engage the public in the process.

As extreme climate events become increasingly common and impactful, those of us who have added the most carbon to the atmosphere have an even greater imperative to take action. This reality has motivated me to pursue my interests at the intersection of peacebuilding and environmental studies. As I anticipate graduating in the spring, I am confident that my experience at the Keough School will serve me well in building my policy-relevant environmental justice career.