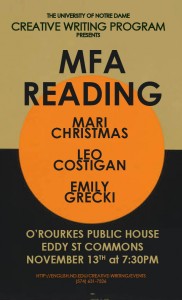

This weekend we ca ught up with ND MFA alum Desmond Kon (2009) as part of our alumni interview series. Kon filled us in on his new book, recent whereabouts, and tons of other new happenings in his life. Read on for more.

ught up with ND MFA alum Desmond Kon (2009) as part of our alumni interview series. Kon filled us in on his new book, recent whereabouts, and tons of other new happenings in his life. Read on for more.

1. What sparked your interest in writing?

Many small moments. This is not an exact science, but I remember my mother placing Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath in front of me. I was six or seven, and I really liked its cover. My dad once gave me the best gift ever – he allowed me to pick out comics from a catalogue – that led to my subsequent obsession with X-Men, New Mutants, Batman, Wonder Woman, Teen Titans, Alpha Flight. At junior college, I started reading lots of fashion and lifestyle magazines like Details, Esquire, National Geographic, Harper’s Bazaar, Vogue, Newsweek, Time. I always mention Ray Gun, which had the most radical design aesthetic ever. Totally jaw-dropping awesomeness.

So it made a lot of sense to major in journalism as an undergraduate. My other major was sociology.Throughout secondary school and university, I wrote and illustrated a great deal, working in different editorial capacities. I guess I was lucky to know my passions and obsessions, what I’d be willing to commit time and energy to. I was writing poetry and fiction right through. Time and distance from the writing has allowed it to gain polish. I’m happy about that because of all the genres, my heart ultimately lies with poetry. As Baudelaire said, “Always be a poet, even in prose.”

2. What current projects are you working on right now?

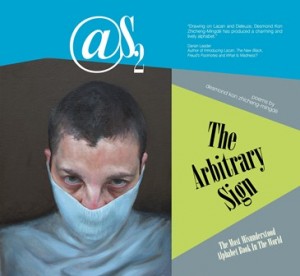

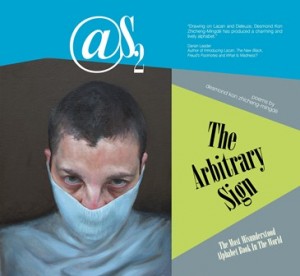

My new book is just going to press, to make it in time for the Singapore Writers Festival in November this year. It’s titled The Arbitrary Sign, published by Red Wheelbarrow Books, thanks to the wonderful work of Chris Mooney-Singh, Savinder Kau r and Marc Nair. The book received a grant from the National Arts Council, so we’re thrilled about that. This book is a playful stab at the quintessential alphabet book, asking questions about meaning through the gaze of the continental philosopher. It tries to elevate the age-old format into something more esoteric – the connoisseur’s poetic aperitif, if you may. My nephews and nieces would balk at its premise.

r and Marc Nair. The book received a grant from the National Arts Council, so we’re thrilled about that. This book is a playful stab at the quintessential alphabet book, asking questions about meaning through the gaze of the continental philosopher. It tries to elevate the age-old format into something more esoteric – the connoisseur’s poetic aperitif, if you may. My nephews and nieces would balk at its premise.

I have another book scheduled to be published late this year. It’s titled I Didn’t Know Mani Was A Conceptualist. It’s by Math Paper Press, the wonderful brainchild of Kenny Leck who runs this awesome bookstore BooksActually. They produce beautiful books, and I can’t wait to see what they come up with.

I have a collection set to come out next year, titled Sanctus Sanctus Dirgha Sanctus. It tears apart the sestina, and through its design, launches the complexity and compression of the line to crash headlong into the blank space of the ineffable.

3. What is the most exciting thing that has happened since receiving your MFA?

Lots of good has happened all around, so much so it’s hard to pin down one thing. Well, something totally awesome and exciting just made my day. I just got word from the National Arts Council that I’ve been awarded the Writer-in-the-Gardens Residency at Gardens By The Bay. I’m totally indebted to the fabulous team at the Arts Council. The Gardens By The Bay is such an amazing world-class attraction, it was named World Building of the Year in 2012. It also hosted Prince William and Duchess Kate when they visited Singapore last year. People rave about the Supertree Grove and Flower Dome and Cloud Forest. It’s really an honor to be able to immerse in it fully – the residency will run for six months, and I’ll be working on a novella written as a series of diary entries.

I’ll be doing several public talks at The Gardens By The Bay. At least one session will focus on Ecopoetics, followed by a writing workshop. Participants will be encouraged to write for an upcoming anthology, Never Never Lalaland: Ecotopia Strangeness, to be published by Squircle Line Press. Never Never Lalaland is the anthology for the green advocate or environmental conservationist. Here is an Ecopoetics that laments, confesses, lilts, dreams, historicizes and fictionalizes. What would an eco-utopia look like? How does one dream of something paradisiacal, yet allow it its foreignness and alienation? What alternative world would such a poem conjure, one already open and willing to be made strange?

4. Yes, you founded Squircle Line Press. Tell us a bit more about this endeavor.

We’re a boutique press, which means we really pay attention to the finer details of putting a book together. We’re big on aesthetics, and do so in order to make your book look its stellar best. We’re excellent with providing editorial consultancy to individual clients a nd corporate entities alike, offering copyediting and design services for a wide variety of books. To view some projects we’ve been happily involved in, please wander here. We’re putting together several anthologies, with an open deadline till enough good work has arrived to make for a solid line-up. We’re in no rush – we just want to make beautiful books. We’ve created our own Reading Room, where visitors will find a list of journals, books, and resources we adore. Here it is. This is some reflection of the sort of work we like, and it is a considerable range from the more traditional fare to the wildly experimental.

nd corporate entities alike, offering copyediting and design services for a wide variety of books. To view some projects we’ve been happily involved in, please wander here. We’re putting together several anthologies, with an open deadline till enough good work has arrived to make for a solid line-up. We’re in no rush – we just want to make beautiful books. We’ve created our own Reading Room, where visitors will find a list of journals, books, and resources we adore. Here it is. This is some reflection of the sort of work we like, and it is a considerable range from the more traditional fare to the wildly experimental.

This year, we’ve focused a lot on our Broadside Series, which can be found here. There are some truly amazing writers on our list, and they’ve got a string of accolades to fill their already impressive credentials. We’re really proud of this Series, and so thrilled that such esteemed writers have come onboard. These are the fifty lucky breaks an artist needs, to quote the actor Walter Matthau.

This year, we’ve focused a lot on our Broadside Series, which can be found here. There are some truly amazing writers on our list, and they’ve got a string of accolades to fill their already impressive credentials. We’re really proud of this Series, and so thrilled that such esteemed writers have come onboard. These are the fifty lucky breaks an artist needs, to quote the actor Walter Matthau.

5. Where are you now, and what does a typical day in the life look like?

I bought and paid off a place in Singapore, so I guess this is my base. I grew up here, and having travelled abroad, have come to love it even more. Its efficiency is splendid for the working writer. There’s always something to eat around the corner, so you don’t need to worry about prepping a weekend trip to the supermarket to stock up. The necessities like banking, utilities, cable, phone services can be done in a jiffy. Teaching is always gratifying, and the youth of the students I meet is wonderfully energizing. Students possess an untouched wisdom prophetic of the critical genius to come of their generation. I like being a witness to that generative process. I read a lot in between things, and always have a book in my bag. It’s Gaston-Paul Effa’s Ma now. I write in bursts, and work on several book projects at once, all of which seem to be coming to a head at this time. The paid work of editing and design, of course, invariably are a priority, and I become the willing and shameless slave, at the beck and call of my client.

6. Who or what influences your writing the most?

My moods influence my writing the most. So I’ve learnt to attend to my moods. To just write whenever I can or must, and then find where the narratives all fit in a larger, more coherent whole. I also work well from an Archimedean point, and that can come from a scene in a movie or a trope that spirals out into its own trajectory. Or a nice poster I walk past in a mall. Or a nice quote I see in a hallmark card. Everything is a text, as the Derrideans say. Everything is a spectacle. So I read everything I can get my hands on. Even pamphlets left in my mailbox. It helps me be real since most writers get heady in the rarefied world of ideas and literature.

7. I noticed you’ve lived a number of different places throughout your life. Are you a big traveler? How does “place” influence your writing, or does it?

I’m fortunate to have parents who believed that travel would open our eyes to the world around us. I’m always thankful for that. My parents took us to Taiwan, Hong Kong and the Philippines in the 1970s, and we saw Japan, Europe and America in the 1980s. My work as a journalist had me covering stories in Australia, France and Spain, while my postgraduate studies found me at Harvard in Cambridge, and Notre Dame in South Bend. That immersion in American culture was mind-blowing, and it was such an incredible time of personal growth for me. I can’t be more thankful for the hospitality, and made awesome friends during that time. Recent years have brought me to the Czech Republic, Indonesia, Korea and Switzerland. I’ve also been exploring more of Malaysia where my grandmother lived out her years – I took a road trip and saw Malacca, Kuala Lumpur, Penang, and Kelantan. I mentioned it in an essay forthcoming in the 2014 anthology Altogether Elsewhere, edited by the lovely Pooja Makhijani.

“Of all possible subjects,” Auden said, “travel is the most difficult for an artist, as it is the easiest for a journalist.” Then there’s John Berryman who said, “We must travel in the direction of our fear.” In my poetry, the mere naming of places creates a presence very different from, say, a person or an object. This naming adds the particular to the space of a poem. For me, the brevity of most poems is more than compensated for the vastness of metaphor a word or phrase within a line might afford. When a place is read as allegorical or metaphorical, there is no end to where the reader might go, or be led into. With place names, how do we contain or encapsulate the richness of history and tradition and culture? That tropic behavior that transcends limits – the boundary of meaning – is what interests me. Of course, I’m always aware of and worry about potentially Orientalizing any culture, which now seems unnecessary given my processing of how I appropriate the notion of place. I think subconsciously this method – to the madness, really – comes from having lived in Singapore, where different cultures mesh, like a plate of rojak, as we say it here. We pride ourselves on this heterogeneity actually, and that people get along despite coming from different countries. We’re a country of immigrants – from when we began until now, when it seems as evident as before. Travel allows me to encounter the new and unknowable “Other” – it reminds me not to take subjectivity for granted, even as I’m constantly jostling within a place of alterity.

8. What advice would you give to current MFA students?

“Never hope more than you work,” as Rita Mae Brown said. Write as much as you can during these two or three precious years, even what seems like doggerel. Keep a vastly open mind when you enter the workshop environment. The workshop shouldn’t be a place to validate your ideas, but rather a place of great learning and exploration. There’s always room for revision and rewriting and rereading and reinvention. Every participant in the workshop is vital to the process, each immediately becoming your reader, ideal or otherwise.

Even though I might have been clueless of it at the time, each of my professors gave me such insight into their own worldview as professional creative writers themselves. The importance of their lessons became evident very quickly after I completed the MFA. Joyelle McSweeney opened my mind to hybrid work, her own fabulous books testament to how writing doesn’t limit itself to stock genres. Then I had Orlando Menes, who took me back to traditional forms, and had me appreciate the sestina and sonnet and ghazal all over again. Those, as well as the important work of translation. With John Wilkinson, it was amazing discourse over the relevance of the lyric today, even as he gave me a long reading list that included Frank O’Hara and John Wiener, two of my favorite writers today. And Cornelius Eady got me thinking about the “event” poem – always difficult to write – and what it means to be comfortable writing through a postcolonial lens. He was my mentor, and his advice has stayed with me. He said: “Do whatever it takes.”

9. What do you feel is the biggest challenge/struggle of being a writer?

Keeping the writing going when the day job leaves you exhausted by day’s end. And getting a book published. Or rather, getting the book you envisioned yourself writing published. I’ve had to learn hard to juggle my work life and the writing life. The upside is I teach what I love. I’ve managed to create and teach new courses, all of which excite me. These include classes in poetry and fiction, children’s writing, literary theory, global and postcolonial literature, and book publishing. And then there’s the editing and design. Just being able to have my life revolve around the literary arts is a real blessing. I’ve cited this anecdote numerous times but I do so here again. Cate Marvin mentioned to me once that she decided a long time ago to go where her poetry takes her. That mantra has stayed with me, and I try to live by it, to steer through to the course. And stay true to the cause, so to speak.

10. Writing alone or in public places?

Both. I’m most productive in my room, and my MacBook is my best friend. That and a set of big-ass headphones that block out all other sound so the music is crystal clear with a deep bass. It’s come to a point where I sometimes find myself muttering to myself at an eatery or in a queue. I must look positively insane. I get a lot of crazy energy in the middle of the night when I’m awakened in mid-sleep. It would be easier to return to slumber but I’ve disciplined myself to haul my ass out of bed and write down these bursts of language while they’re still fresh.

11. What do you do in your spare time?

Here’s something from Nadine Gordimer: “Writing is making sense of life. You work your whole life and perhaps you’ve made sense of one small area.” I’m only just beginning to really understand what this means, and boy have I half a lifetime’s worth of trauma and neuroses to unpack, with no end in sight. I’d like to say that I have a life – that would be chic – but I really don’t. I’m a through and through geek, replete with the thick black nerd spectacles. My philosophy is any energy I’m expending on something could be energy I’m using to formulate a storyline or rewrite a poem or put together the chapters of my next book. It has become a deep commitment that I attend to the language in my head, at all hours of the day, as much as I can. I think it’s a kind of service, not in some grandstanding way but in a real nod to the self. That this is what I hope will obsess me for the rest of my life, and cull me the happiness I’ve desired all along. I really can’t imagine being more useful to society in any other way.

KON’t get enough? Check out Desmond’s website here and keep an eye out for his forthcoming book, The Arbitrary Sign.

Cheers!

Julia ’15

Tags: alumni interview, Alumni Interviews

This year, we’ve focused a lot on our Broadside Series, which can be found

This year, we’ve focused a lot on our Broadside Series, which can be found