Post by Will Chronister, University of Notre Dame Undergraduate Researcher

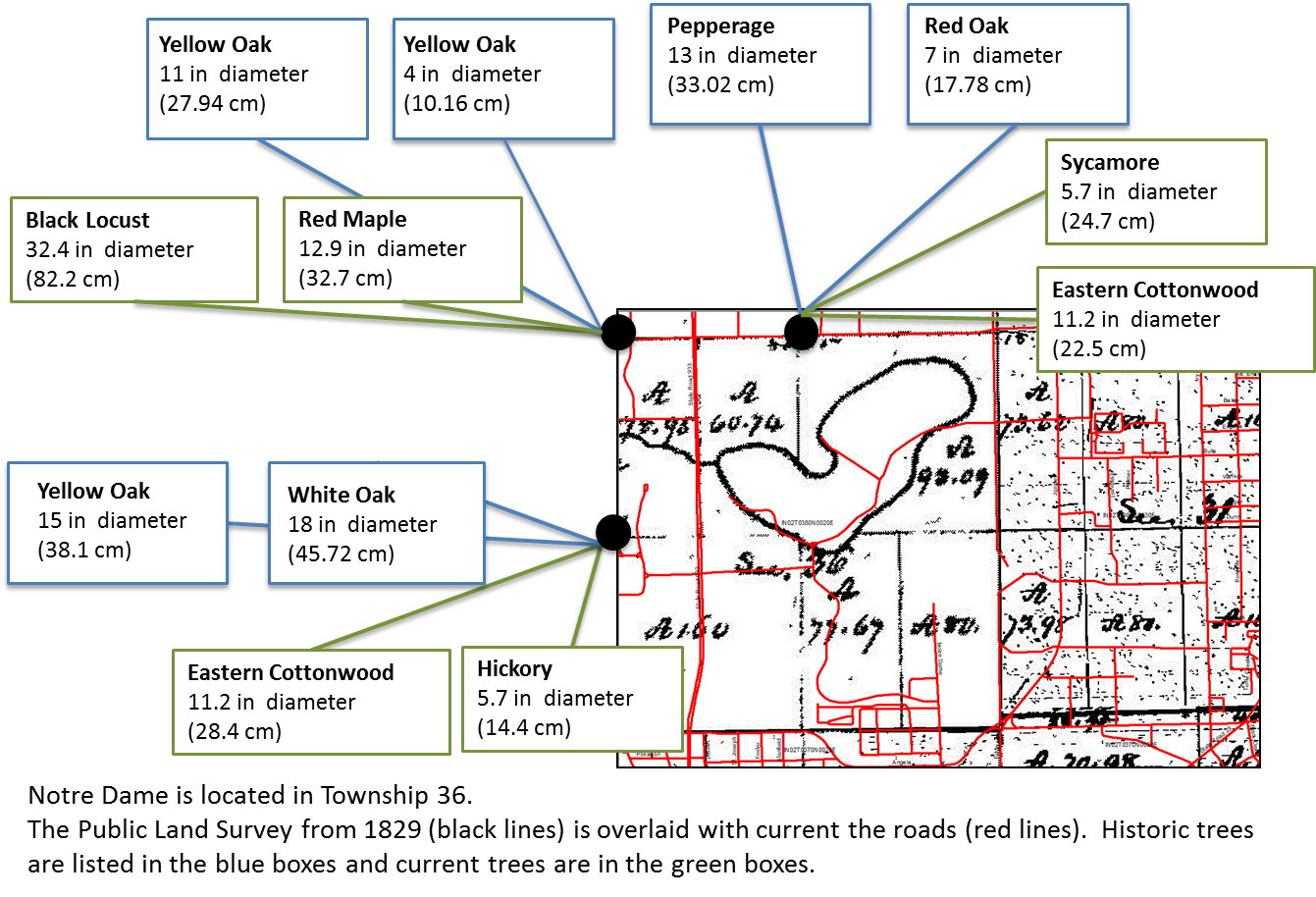

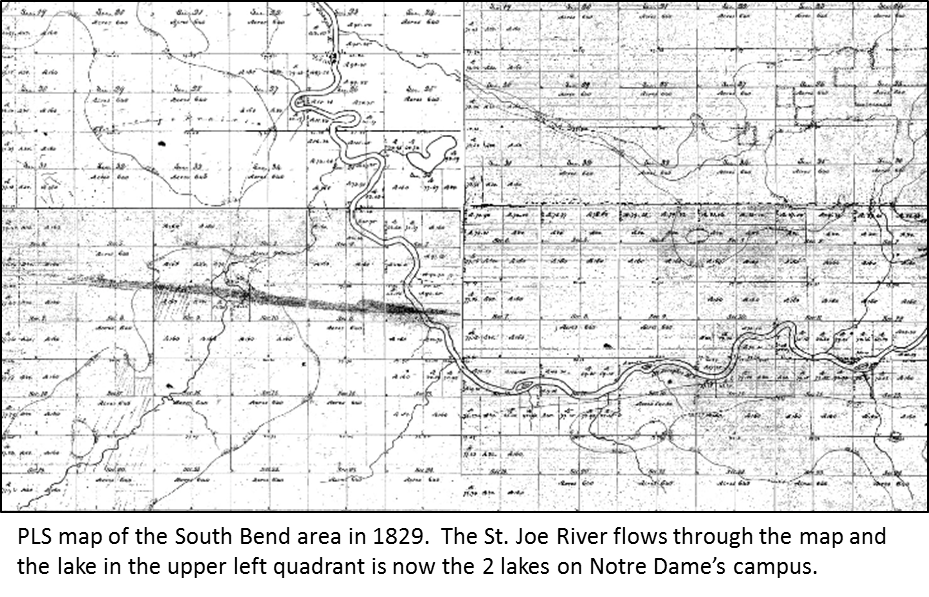

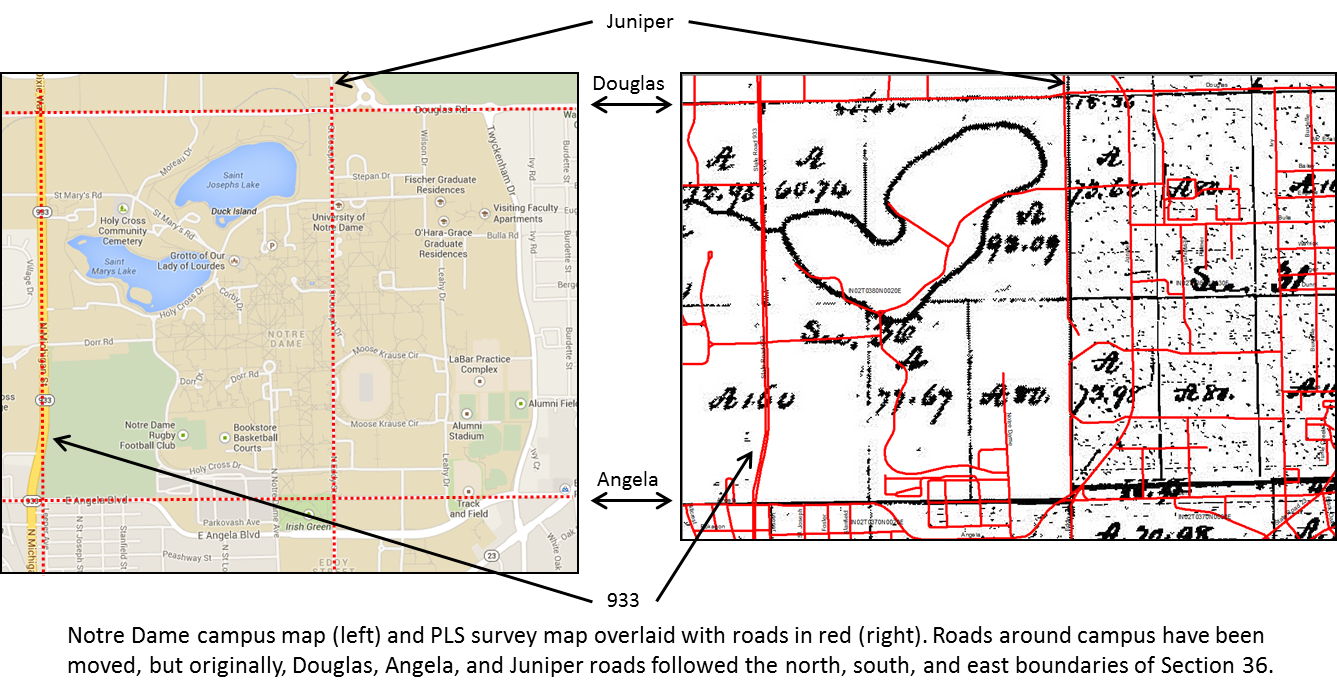

My project within PalEON explores the Prairie Peninsula, an intriguing feature of the pre-settlement Midwest that consisted of a bulge of prairie into Illinois and Indiana where forest was prevalent in surrounding areas. Human settlement and agriculture essentially wiped out the Midwestern prairie and replaced it with farms, towns, and forests, but in 1935, Ohio State University ecologist Edgar Transeau depicted the region as it originally existed. Transeau based his map on information contained in Public Land Survey (PLS) notes, which provide information about the landscape and were recorded when the land was first being explored and sold. However, Transeau’s map, while useful visually, lacks any accompanying data to characterize the prairies and forests of the time, and therefore has questionable accuracy. Furthermore, the map interestingly contains no indication of a prairie-forest transitional region.

In order to learn more about the Prairie Peninsula and determine the accuracy of Transeau’s map, we are gathering Illinois and Indiana PLS data from the old survey notes in townships within and around the Peninsula. This is helpful for my personal project and also contributes to the overall PalEON effort of collecting data from all of pre-settlement Illinois and Indiana. When we have enough townships completed, we will create a map of the vegetation and compare it to Transeau’s map. In addition to testing Transeau’s map, we will also look into the causes of the Prairie Peninsula, which may include such factors as precipitation, soils, hydrology, and so forth.

Ultimately this research is important for a couple of reasons. Firstly, it will be beneficial to confirm Transeau’s map of the Prairie Peninsula and/or create a better one so that we have an accurate picture of the 19th century Midwest. Secondly, if we can pin down the causes of this irregular region of prairie, it will inform the study of modern-day environments where the same processes could be taking place. Given the potential effects of climate change, the need to understand what causes a prairie to thrive in place of a forest, as well as other biome patterns, has never been more pressing. Our hope is that our research of the Prairie Peninsula can be a small contribution to this much-needed knowledge.