![]()

Name: Andrea L. Castonguay

E-mail: acastong@nd.edu

Location of Study: Fez, Morocco

Program of Study: Arabic Language Institute in Fez

Sponsors:

![]()

A brief personal bio:

I’ve just completed my first year as a History PhD student at Notre Dame, focusing on the medieval Muslim Mediterranean in relation to other medieval peoples and civilizations. For me, this past year has been about laying the necessary foundations for subsequent coursework in Islamic history. Already, I’ve translated diplomatic correspondence between kings in Spain and Algeria, submitted a bibliography of Arabic primary source material, and began reading medieval Arabic chronicles. This fall I will study the historical and theological origins of Islam and its spread to non-Arab peoples, and the construction of historical narrative in Arabic literature.

Why this summer language abroad opportunity is important to me:

As a historian studying the inhabitants of medieval Morocco and their relationships with the wider Mediterranean, the ability to speak, read, and write in Arabic is essential. For instance, a solid knowledge of Arabic is essential in order to make use of documents in the National Library of Morocco. In turn, access to this information opens up a rich avenue of scholarship long ignored by western historians, which gives me an advantage in the wider field of medieval Mediterranean studies. The ability to speak, read, and write both Modern Standard Arabic and Moroccan Colloquial Arabic will allow me to communicate with other Arabic-speaking historians both inside and outside of Morocco and incorporate their perspectives into my research. Finally, as a student of medieval Morocco, living and studying in the medieval city of Fez will give me a deep, first-hand knowledge of this important city. A personal familiarity with the city’s landmarks and districts will illuminate descriptions in primary documents, allowing me to understand the ways in which Fez’s medieval inhabitants organized and oriented themselves in regards to their neighbors and in physical space. Not having this opportunity would seriously handicap my professional development and irrevocably alter my course of study.

What I hope to achieve as a result of this summer study abroad experience:

My larger goal is to achieve full professional mastery of the Arabic language by the time I submit my PhD Dissertation Proposal in the spring of 2016. This means that I will need to have completed three years of university level coursework in the language. My more immediate goal is to progress from an advanced beginner to an intermediate level. My previous language study and coursework allowed me to place into ALIF’s 300 level course instead of the 200 level, and the intensive language program at ALIF covers an entire semester’s worth of study in just six weeks. Thus, I will progress rapidly from an advanced beginner to an intermediate level and enroll in a more advanced level of language study in the 2014-2015 academic year, including taking Arabic literature courses taught entirely in Arabic. Once I achieve this goal, I will return to ALIF in the summer of 2015 in order to progress once more from a high intermediate level to advanced proficiency in Arabic. This will then allow me to complete my comprehensive exam fields and progress to the PhD Dissertation Proposal during the 2015-2016 academic year.

My specific learning goals for language and intercultural learning this summer:

1. After undertaking my program of study at ALIF, I will be able to converse in Arabic on a number of topics and in a variety of situations, from daily interactions with native Arabic speakers to professional discussions in an academic setting on what I study and why.

2. After completing my course of study, I will have a stronger understanding of Arabic grammatical forms and functions, as well as a richer vocabulary. This means that I will not need to rely on a dictionary or grammar books as much when reading and translating Arabic texts and primary source documents, thereby allowing for me to read more material at a faster pace.

3. When I return to Notre Dame in the fall, I will have the skills necessary to enroll in intermediate Arabic courses instead of an advanced beginner level. This means that I would be able to take the Arabic Language Comprehension Exam in the Spring, demonstrating my language proficiency and thereby completing my language requirements for the History PhD.

4. After attending the various cultural programs offered at ALIF as part of the overall language course of study, I will have a much more intimate knowledge of Fez, its history and how it relates to the dynastic histories of medieval Morocco. In addition, the various presentations and events will introduce me to Moroccan historians and scholars, allowing me to make professional connections necessary for future research.

My plan for maximizing my international language learning experience:

Getting the most out of my language classes and my experience in Fez is one that requires both intensive study during the program and preparation in advance. In order to ensure that I would be able to meet this expectation, I have spent the past several weeks reviewing the foundational principles of Arabic grammar such as verb forms, tenses, and cases, making flashcards of Arabic vocabulary, and discussing principles of Arabic grammar with other Arabic students in order to address any questions I have. As a means of improving my reading comprehension and translation abilities, I have been reading Ibn Ath?r’s (d. 13th century) historical chronicle Al-K?mil f? al-Tar?kh for several hours a week for the past month. With regards to listening comprehension, I have been listening to recordings of Arabic language stories and fables, as well as contemporary Arabic music. Finally, I purchased the textbooks and workbooks associated with the program at ALIF and reviewed the chapters I will study as part of the course. Thus, by the time I begin coursework, I will be accustomed to the demands associated with studying and mastering Arabic.

![]()

Reflective Journal Entry 1:

Reflective Journal Entry 2:

Blog Post # 2 “Language”

What exactly is Arabic?

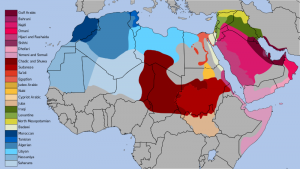

Ostensibly, I’m here in Morocco to continue studying Arabic, a semitic language that goes back approximately 1500 years. It is closely related to Hebrew and Syriac, and is spoken by over 290 million people as a first language.

However, just like all other languages, Arabic has changed dramatically over time. The form I’m studying now, Modern Standard Arabic (MSA) or Fus?a, is a simplified version of what is known as Classical Arabic, that is, the language of the Qur’?n. MSA is what is taught in schools, and it is used in more “official” spheres, such as news broadcasts and international relations, and it is used in literature. Academically speaking, I’ll need MSA in order to read academic publications and modern editions of medieval and classical texts that my advisor is already assigning en masse.

Yet most people do not speak this version of Arabic. Instead a different version of Arabic governs day-to-day interactions, movies, television, and social media. Often called a dialect, Derija (or ‘Amiya in the Levant) is a form of Arabic that takes its cues from the cultures and peoples around it. Sometimes, there is not that much of a difference between the Modern Standard and Derija forms but most of the time, the gulf between them is quite wide, and different Derija speakers have to speak in MSA in order to understand one another.

Perhaps the best way to describe the difference between MSA and Derija is to compare it to Latin and its Romance derivatives. To some degree, Spanish, French, Romanian, Portuguese, Italian, and all the others in-between are evolved forms of Latin. They do not belong to other groups of languages, like Germanic or Slavic, but are present day variations on an ancient language. Likewise, some of these variations are comprehensible to non-speakers, like Spanish and Italian, but the gulf between others is too great to allow for comprehension.

Derija functions in much the same way. Right now, all variants are classified as “dialects” of Arabic but it might be more accurate to think of them as separate languages. Folks from Morocco can’t understand those from the Gulf and vice versa so MSA acts as the lingua franca as it were, between the two regions.

At ALIF, classes are taught in MSA and in Moroccan Derija, with Derija heavily influenced by the various Berber languages, as well as French and Spanish, depending upon what region of Morocco one is in. Buying things in stores, I find, is sometimes a little difficult as the clerks expect me to speak Derija instead of MSA and I have to say, rather apologetically, that I only speak MSA. When in doubt, I fall back on French to fill in the gaps with my MSA, which seems to go over easier than just strait MSA. As time goes by, I’m sure that I’ll pick up bits of Derija here and there in order to better understand what’s being said around me but for now, it’s going to be the more “taught” variant of Arabic than the day-to-day version.

Reflective Journal Entry 3:

Blog Post #3 “Architecture & Local Flavor”

As of late, I have been obsessively staring at buildings.

One of my reasons for studying in Morocco has been to immerse myself in the country’s physical landscape. The way a place looks, from its climates to its peoples, affects the direction of one’s research. As detailed as descriptive writing can be, it is impossible to completely convey every physical aspect about a place solely through verbal description alone, especially if there is a difference between an author’s and reader’s knowledge of the place in question. One needs to physically go to the place in question, to hear its noises, talk to its peoples, study it physical features, and touch as much as is allowed.

Which brings me back to my fascination with architecture.

Long ago, I had studied in Seville, Spain in order to deepen my own understanding of Spanish cultures, especially those found in the south of the country. During my time there, the usual pilgrimages were made to Cordoba and Granada, and to various places and points of interest within Seville itself, such as the Torre del Oro, the Cathedral, and the Alcazar. I know I took many photos but it’s safe to say that back then, I was regarding each place as part of a unified whole. Granted, there were architectural differences between the Great Mosque in Cordoba and the Alcazar in Seville, but to me, it was all lumped in under the category Islamic Art. Moreover, Islamic Art was this unchanging entity perfectly preserved until the modern. What I saw in Spain I could see in Islamic countries like Morocco.

Now, however, I know better.

On my way to Morocco, I stopped off in Seville again and noticed how all of the Islamic Art littered throughout the city was not this unchanging lump. The differences in styles were as pronounced as those which exist in European Art. Even in a place like Seville’s famous Alcazar, there were two very different Islamic styles, each corresponding to a different point in time.

This multiplicity of Islamic Art styles was further underscored when I got to Fez. There, Islamic Art disappeared as a category altogether. Instead there were different styles, some which corresponded to dynasties and others which correspond to location. For instance, in Morocco, religious buildings like mosques and madrasas (schools) have green roofs. This is not found in other Muslim countries like Egypt or Turkey but is unique to Morocco, underscoring the importance of geographical influence upon art and design.

In addition, there is also the question of what is a country’s national style and how that affects our understanding of the past. For Morocco, the national style appears to be a mixture of what can be dubbed Almohad features such as square minarets, Marinid designs like geometric tile work and highly floral and abstract plaster carvings covering everything, and a number of other visual clues and features taken from different sources that I can’t even begin to name. Yet all of these elements are pulled together, creating a new vocabulary of buildings, making it easy to confuse the past with the present. In many respects, this “national Moroccan style” is not at all unlike the NeoGothic and NeoClassical movements in European architecture, which in pursuit of a past time crammed a bunch of influences together, effectively creating a whole new aesthetic.

Even the building where my classes are held is the result of this new ascetic. The plaster carvings and tile work are modern retellings of many visual tales. Even the updated riads and dars in Fez’s old medina make use of this new language, creating something new in pursuit of something perceived as “old” or even “authentic.” Bab (Gate) Bou Jeloud strives to imitate Marinid designs and to the untrained or unaccustomed eye, it succeeds.

Yet the older style-buildings, the palaces, the ruins, and the minarets of Morocco say otherwise. They are the physical embodiments of the fact that so many different styles existed over time, and that the visual language that is a “national style” is more creation than mere replication. I certainly didn’t know enough to tell the different when I encountered this same phenomena in Spain all those years ago but now here in Morocco, I find myself looking up and every building and taking note.

Reflective Journal Entry 4:

Blog Post #4 “Food”

The last time I ate tajine on a regular basis was when I worked in a Moroccan restaurant staffed exclusively by El Salvadorians.

Then, I ate tajines, lubia, harira and other Moroccan dishes because I was 18 years old, had very little money for groceries, and was allowed one free meal per shift so it was a good way to get some calories. We listened to the various Arabic pop cds the owner provided while speaking in Spanish and scarfing down our lunch or dinner long after the crowds had left. I remember encountering lots of spices I had never had before (my own family’s food was always on the blander side of seasoning, with oregano being something exotic, reserved exclusively for pizza and spaghetti sauce) and eating harira, the cinnamon scented, tomato-based lentil, chickpea, and vermicelli soup topped off with a lemon quarter and fresh parsley, until I was stuffed. I learned to enjoy beans (another food I had only known previously in their sweet, hammy “baked” form) and learned how to cook them, which came in handy the next year when I was living on even less money. A $2 bag of dried lentils will give you a number of pretty filling meals, though you may get sick of eating them. Eventually, I reached my saturation point and exchanged my mostly Moroccan-inspired diet for other types of (equally cheap) foods and cuisines.

When I arrived in Fez ten years later, the first thing I did was order couscous. The school has a small food kiosk on its grounds which serves small breakfasts, soups, tajines, coffees and copious amounts of mint tea. I ordered in Arabic — wahid couscous, min fadlak — and sat down to a very familiar sight. The plate was heaped high with well-cooked but colorful vegetables, plump, sweet raisins and tender chickpeas, and the smell of cinnamon. Nestled under the vegetables I found several pieces of well-cooked chicken whose meat easily fell off its bones. Supporting all this weight was a pile of fluffy couscous, the small, ball-shaped pasta dish that is Morocco’s answer to Sunday Dinner. When I was done, I had the familiar lump of filling satisfaction that I remembered from my meals at the Moroccan restaurant.

There are a few differences, this time around. For starters, the cooks at the kiosk are two Moroccan Muslim women, not four Salvedorian men. Conversations are in Arabic (MSA or derija) or French, instead of Spanish. Second, the women listen to a recording of the Qur’?n being recited while serving up tagines. Third, during Ramadan, there is no meal or water break for them until sundown when the cannon is fired announcing the official onset of dusk. By that point, the kiosk has closed and the women have gone home to their families, a far cry from the very late nights that I and the rest of the staff at the restaurant used to work.

Finally, the only cooking that students have to do is the cooking class they sign up for. I readily part with 40 dirhams and join the two women in the kitchen of the student villa where I live one Monday night.

This particular night, the meal we’re learning how to cook is dejajj m3a barkok, chicken tagine with prunes. Not only is the whole class is in Arabic, with MSA and derija words given for the food items, but the meal preparation itself is very Moroccan. There is no cutting board, no knife bigger than a paring knife, and no cooking equipment fancier than a pressure cooker or a Cocotte-Minute as it is known in Morocco. The women teach us how to cut an onion (ba?el/buzzul) while holding it in our hands, shredding its red flesh over the pieces of chicken (dejajj) at the bottom of the pressure cooker. For smaller pieces, the grater reigns in Moroccan kitchens; everything from tomatoes (tomatim) to garlic (thumm/?umm) to bouillon cubes are grated over the pot. Spices are thrown in with the careful carelessness that comes only from years of experience of cooking, though I’m surprised to see a smaller variety than I expected.

One of the older students asks why we’re using the pressure cooker instead of one of the clay tagines that line the sideboard. “Isn’t that more traditional,” he asked.

“Yes,” they reply as they crank on the pressure cooker’s lid. “But this takes only half an hour, whereas the tagine takes an hour and a half or more. Now, the pressure cooker is traditional. We just serve the food in the tagine.”

While the chicken cooks away, we move onto the prunes. They are all dried, but about a cup of water is added to a small pot, along with an equal amount of sugar. Moroccans, it should be noted, like their sugar. “This will make the sauce, which we will pour over the chicken once it is done,” they explain. “Its what gives the dish its flavor.” My question about the quantity of spices is answered before I even ask it.

As we stand around the table and count down the remaining minutes, the women turn to ask and start to ask us questions. “What’s your name? Where are you from? Have you studied Arabic before?” To those using more French than Arabic to get by, they ask (in Arabic) how this language was acquired as well. They detect any “foreign” influences in our vocabulary, such as the use of Egyptian or Shamsi (Syrian) colloquial in our speech, things that we ourselves are not aware of, and take the time to write down (in derija) more detailed instructions on how to make dejajj m3a barkok.

Its interesting to observe this group of students, so obviously far more educated and travelled then these two women, stutter, squirm, and act bashful in their presence. Polite questions about the women’s lives are asked, but only what could pass for basic pleasantries. In contrast, the two women are calm, comfortable, and very clearly in charge. The ease of their movements and the frankness of their questions — Are you all university students? How long have you been married for? Do you have any children yet? What’s your family like —mother, father, brother, sister?— communicate to us that we are the interlopers, though we should feel welcome all the same. Like good hosts, they absolutely refuse that we help with the final setup of the table, or the subsequent cleanup.

Instead, they usher us into the sitting room (wrufat jalus/salon), place the large tagine full of the tender chicken and sweet prunes and command us to eat. We insist that they sit with us, but they will have none of it. “The lesson is over; eat” they say before wishing us bon appetite. We try to insist one more time but the women are firm. So, with nothing left to do, we all rip the bread apart and soak it into the mixture of syrupy prune liquid and chicken fat, smacking our lips and gratefully mumbling “ladeeth jiddan” — very delicious—until there is nothing left but the bones.

Reflective Journal Entry 5:

Post #5 “Chefchaouen”

Throughout my weeks here in Morocco, I’ve certainly been falling back on French to fill in the gaps with my Arabic. It is certainly one of the most lasting colonial legacies of modern Morocco, and I am not the only student here who finds themselves reaching for it on a semi-regular basis. Going into any shop or café instantly merits a “bonjour” from the staff, though a reply of “salaam” and the familiar expression “keyfa hal” or “keyfik” tends to generate a reply in Arabic or Derija.

That persistent presence of French vanished, however, going up to Chefchaouen in the Rif Mountains.

Here in this blue colored town nestled into a mountain side, the language one falls back on instead is Spanish. Whereas Fez and other cities of Morocco have their ville nouvelles — the “new cities” established by France as part of their colonial apparatus — Chefchaouen has a ciudad nueva with a plaza designed by the Catalan artist Joán Miró.

Likewise the main space in front of the kasba (fortress) in Chefchaouen’s medina is the Plaza Uta al-Hammam, not the Place. Signs are given in Arabic and Spanish, with French relegated to third place, and the signs themselves are the blue-on-white tiled ones I’ve seen in Spanish cities. A number of the hotels, hostels and guest riads and dars (Moroccan-style houses) are named “Hotel Madrid,” “Granada” and, where I stayed with several friends “Hotel Gernika,” reflecting the culture and language of its Basque owner. Young Moroccan children shout “hola” instead of “bonjour” as I pass — and their elders call my friend from Singapore “chino” — although I do notice a number of Spanish tourists wandering the narrow streets, arguably the largest concentration I’ve seen since taking the ferry to Tangiers from Tarifa.

Tourists aside, the presence of Spanish throughout this part of Morocco relates back to the first half of the twentieth century, when much of modern Morocco was the Spanish Protectorate in Morocco. Here, the metropole was based in Madrid, not Paris, with Spanish was instituted as a language of power and of European association. The provincial capital of the Spanish Protectorate, Tetuan, is just under a hour’s drive from Chefchaouen. While all that remains of the Spanish Protectorate of Morocco are the port cities of Ceuta and Melilla —effectively marking the distance the Protectorate once spanned — the continued presence of Spanish as a language in Chefchaouen is as much a nod to this area’s colonial past as the use of French is in Fez. One taxi driver explains that he can speak Standard Arabic, Spanish, and French with the same dexterity, a feat that no taxi driver I’ve had to date in Fez has laid claim to.

My brain is somewhat stunned by this simple linguistic shift. When speaking in Spanish, I find Arabic slipping in as well. In shops and restaurants, I am momentarily paralyzed as I wonder what language to use. Somehow, English never comes up as an option, which could be testament to the fact that I now rarely use the language for daily life.

One part of this particular colonial legacy I notice in the ciudad nueva is a church. Churches were certainly constructed as part of the colonial endeavor in many ciudad nuevas/ville nouvelles but other than Tangiers, I haven’t see any. Which is why I had to take a moment to confirm that yes, this church-like building is indeed a church. Its architecture instantly recalls similar churches in Spain, right down to its placement in front of an open space. Perhaps a little ironically, the building is no longer used as a church, mirroring the repurposing of mosques in Spain as control of cities, spaces, and lands shifted to a new group of colonizers. Where exactly “colonizers” begin and end, though, is rarely clear cut. The constant echo of Spanish throughout Chefchouen seems to indicate that taking over a building is the easy part.

Reflective Journal Entry 6:

Post #6 “The End”

Today everything comes to an end.

A little over six weeks ago, I arrived in Morocco from Spain by boat. I travelled five hours by train down from Tangiers to Fez, watching the coastline recede into the distance as we went across the plains. Today I’ll fly away, crossing the sparsely populating mountains to the northeast and landing in Marseille in just under two hours. I arrived in Morocco using a form of transportation thousands of years old but now I’ll leave on one just a little over than one hundred.

I arrived in Morocco with the ability to haltingly read and translate Modern Standard Arabic (MSA) and now I leave able to haltingly converse in MSA as well. This ability to speak very badly does appear to win some temporary friends and allies. My driver on the way to the airport points to his own language book on the dashboard and says he is a student as well. English, he says, it the language everyone in studying in Morocco both because it is perceived as an international language and because after years of French and Spanish colonization and wars, both languages have lost much of their appeal. But, as he explains in MSA mixed with Derija [hyperlink to Blog Post #2 on “Derija”], I can only say simple short words now: “Hello! How are you? Thank you! Have a nice day.” Just like me and my Arabic, I reply. But English is hard; it doesn’t have nice, neat rules like the ones which exist in Arabic. One day in the future, insh’ Allah, you’ll be better. We’ll both be better.

He laughs and says, yes in the future, insh’Allah.

Slightly similar conversations are played out at the airport as I clear customs, wait to have my passport stamped, and pass through security. I only lapse into French once, when needed to explain that I had come into Morocco on my old passport several years ago, which is why my new number doesn’t match that old record. Once that’s taken care of, it’s right back to Arabic. Based on past experience, I know that I’ll find myself trying to speak Arabic with those who can’t in the near future, simply because I have become so used to this language during these short six weeks. You readers have certainly noticed it creeping into my posts and I can’t tell you how hard it was for me to not write the phrases using the Arabic alphabet.

So while I stand waiting for my flight, I try to get as much in as possible during these last moments. I test my luck in reading the MSA subtitles running at the bottom of the television screen. Most of the time, I can’t read as quickly as the words appear on screen, but when they linger I can pick out a word or two. Mostly, I’m trying to pay attention to the ways in which the English dialogue is translated into MSA, especially when it comes to some of the more colloquial speech. One thing I do notice is the way in which words agree grammatically. It’s much easier for me to find the relationships between subject and predicate, or nominative, accusative, and genitive, or even the dreaded dual form (of which there are three) that it was six weeks ago.

All that said, I still have a long way to go in terms of mastering this language. At least now, my grammar is solid. That will certainly help carry me as I start the next round of classes this fall.

![]()

Reflection on my language learning and intercultural gains:

I started this enterprise with the ultimate goal of achieving full professional mastery of the Arabic language in time for my Ph.D. Dissertation proposal. On paper, the path is clear-cut and remarkably straightforward. Studying Arabic over two summers as part of an immersion program, in addition to undertaking language study during the fall and spring terms, would strengthen my abilities, deepen my knowledge of the language, and open up a rich world of primary source material perviously off-limits. This path is also noteworthy for its depending independence. As I progressed in my course of study, I would abandon the various aids which had helped me in the past, such as grammar books and, once reaching professional mastery, teachers.

What I’ve found over the course of this summer’s study is that said path omits much of the actual reality. One can certainly progress in terms of class level, but those progressions are not as even or as equal as they look on paper. Although I was eventually placed in an accelerated 200 level class, I found myself explaining grammar points to students in higher level classes. At the same time, for every step forward on my path towards language proficiency, I found that I many mini steps backwards, often many times. In class, we simply did not learn a grammar point and move on. Rather, we retraced our steps, revisited the concept over and over again, and, at times, jogged in place. Moving on to a different chapter in our textbook certainly helped to mark time and measure progress (along with the increasing amount of vocabulary and expanding folder of notes), but in the thick of things, time often felt as though it wasn’t moving linearly. Similarly, my language ability also felt suspended. Speaking haltingly wasn’t exactly the type of goal I had set down, and it seemed as though moving to the next level was never going to happen.

Finally, the more I studied, the more I relied on resources and colleagues. It wan’t enough to simply read the textbook and go from there. What this new nascent knowledge allowed was the recognition that there were additional means of deepening my understanding. Asking for help, whether it was proofreading a composition or trying to find the hidden subject in a sentence, was an a ability that grew over time. It was also one of the things that I knew I would miss the most when my time came to leave ALIF.

Yet if the acquisition of an ability is a more complex reality than a straightforward plan lets on, there still remains movement forward. The shear fact of having logged 240 hours of language study means that some progress forward was made. True, I may have felt suspended in time over the summer — and my advisor says I have a long way to go in terms of achieving full professional proficiency— but reentering the academic world here at Notre Dame throws into sharp relief just how much movement forward actually occurred. Now, I am not scared by the process of working with primary Classical Arabic documents this fall (though that idea still is intimidating). I may certainly be in over my head in my Arabic class, but that is more due to a lack of specific vocabulary than a deficiency in my language abilities. It just means that I’ll have to work twice as hard in catching up, both in terms of speaking and in vocabulary acquisition. At any rate, the professor said that the class was designed to help everyone out regardless of their particular strengths and weaknesses. Insh’ Allah, the next 240 hours will bring me that much closer to meeting my goal.

Reflection on my summer language abroad experience overall:

Overall, the weeks I spent in Morocco were both highly productive and illuminating. Certainly, most of my time spent studying, but the various interactions I had with other Arabic students and Moroccans, be it in a cooking class or while traveling to other parts of the country, were ones that couldn’t be replicated by staying in the US. In fact, it was the small detours and unexpected findings which were the most memorable. The journey I took to Morocco from Spain not only allowed me to experience a much more ancient way of crossing but also brought me into contact with the physical reminders of how tied the two places are. Being in Morocco and taking in the physical sites of its buildings day in and day out made me realize just how much I had been glossing over the country’s visual culture and artistic history. Experiencing just how MSA Arabic, Derija, French and Spanish interweave in daily life made me realize just how much language doesn’t confine itself to strict academic boundaries. In short, the very topics on which I reflected upon in this blog would not have been possible had I simply stayed back in the States and studied on my own.

How I plan to use my language and intercultural competences in the future:

The most immediate application of my newly improved language skills will be to continue my course of study in the fall. With any luck, I will be able to complete the second year Arabic program at Notre Dame before I return to Fez for additional language study in the summer of 2015. In addition, I intend to continue working with primary source documents, such as Arabic language histories and chronicles in order to build my abilities and conduct preliminary research for my dissertation. It is decidedly not glamorous work but it is practical and applicable, and those two things of the utmost importance to the Ph.D student.

The bus from Seville left at 9:30 am and arrived at Tarifa just before 12:30. The cab from the bus station took me to the ferry terminal, right by the castle overlooking the Strait of Gibraltar and across to Africa.

I had been here once, almost a decade ago as an undergrad and I had wandered around that very castle. It had been built in the tenth century during the Umayyad Caliphate of Cordoba and was captured, several centuries later, by the crown of Castile-León. The story goes that when the castle was being attacked by the King of Castile’s younger brother and his Marinid allies from Morocco, the holder of the castle refused to surrender, killing his own son instead as a means of showing the strength of his resolve. I don’t have time today to wander through the castle’s walls or see the curved Moroccan-style swords on display inside, nor try to read the Arabic inscription above the entrance to the inner fortress. The ferry leaves at 1pm and it’s a long train ride from Tangiers to Fez.

After a slight mix up, I get a copy of my boarding pass, go through Spanish customs and board the boat. What is going to be a very easy and legal process for me is one that is fraught with danger for others. The Straits are a tremendously busy point of migration for those moving north into Europe. The singer Manu Chao sang about the dangers of crossing almost twenty years ago, saying that he “left his life between Ceuta and Gibraltar.” Even though my crossing is fairly smooth and the weather is good, I feel the power of the ocean underneath the large ferry. I can only imagine what I might be like to be in a much smaller boat and for someone trying to come in without any papers.

Customs are taken care of before we disembark. The announcement comes on several times in the 45 minute crossing, reminding passengers in four languages that they need to have their passport stamped before disembarking. I stand with a large crowd of strangers before a small kiosk tucked away in the back of the boat, squeezed in-between the college aged students with French and English passports and a Spanish couple, the husband puffing away on an e-cigarette while complaining about the line. My passport is stamped with little effort and I retrieve my bags. No doubt I’ll need to get a taxi to my hotel, though what the going rate is for a cab is, I don’t know.

Just before I disembark in Tangiers, I notice a small castle abutting the ocean. Less than eight miles separate Tangiers from Tarifa and yet fortifications are on both sides. Perhaps both defenses were constructed by a single power. Instead of being antagonists, they are watchtowers, protection against whomever might come in from the Atlantic or from further down the Mediterranean.