Iceland is a country more aware of its medieval past than many- if not most- modern nations. One cannot walk down any of the main thoroughfares in downtown Reykjavík without spotting Viking paraphernalia for sale: keychains, T-shirts, drinking horns, helmets- you name it. But this sense of the past extends far more deeply than a desire to part willing tourists from their cash; rather, many modern Icelanders still know the stories of the settlement of Iceland starting in the 9th century, to the conversion to Christianity in 1000, to the end of the Icelandic Commonwealth in 1262. When I told one bookseller that I was studying the Icelandic sagas as part of my PhD, he was so pleased he gave me an edition for free! Many Icelanders are very proud of these early settlers who came to cultivate what was often an unwelcoming terrain. One of my summer course instructors told me that in the early 2000s when Iceland was enjoying what appeared to be vast economic success, the bankers and businessmen involved with Iceland’s finances were proudly hailed as the “new Vikings.” Enthusiasm for these vikings soon waned with the economic crash.

Almost the entire first floor (of two exhibit floors) of the Pjóðminjasafn Íslands (National Museum of Iceland) contains medieval artifacts from the Viking Age and post-conversion period. Below on the left is pictured a very famous statue of (most likely) Thor, believed to be carrying his famous hammer Mjolnir before him. While Odin was the chief of the Norse gods (known as the All Father), Thor was immensely popular and has given his name to numerous places and people. Many Icelanders contain names with “Thor” in them today (Thorstein, Thorvald, Thord, to name a few examples). In more recent decades, this statue of Thor has been reused in modern advertisements. Below (on the right) it is included in an illustration with the seated figure eating licorice instead of holding the hammer.

Then and Now:

Medieval Icelanders also produced exquisitely carved decorations which often adorned churches. These interlace patterns usually included flora and fauna, sometimes depicting human beings as well.

With the exception of Leif Erikson, the most famous medieval Icelander is probably Snorri Sturluson, known for writing down the Norse mythological works in a collection of texts which has come to be known as the Prose Edda or Snorra Edda (The Edda of Snorri). Below is a statue of Snorri at one of the places he lived (and was murdered in 1241): Reykholt. You can also see me pictured with a pool of water on Snorri’s property. As it has been dated to the medieval period, Snorri may have used the pool himself.

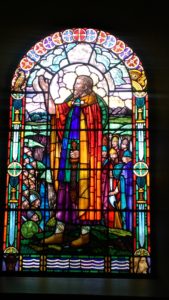

The Church at Bessastaðir, a place very near Reykjavík, contains a series of stained glass windows depicting the history of Christianity in Iceland. Though built in modern times, a few of these artworks depict medieval subjects. According to Landnámabók (“The Book of Settlements,” dated to around 1200) and Íslendingabók (“The Book of the Icelanders,” dated to the early 12th century), Irish Christians (likely monks) were in Iceland before the Norsemen arrived, leaving some of their property behind.

Depicted in the stained glass window below is Thorgeir Thorkelsson, the Law-Speaker of the Althing (Iceland’s governing body) at the time of the conversion around the year 1000. Though a pagan himself, he decided that the country should become nominally Christian in order to avid conflict; however, he said that pagans could continue their practices in private.

In addition to depictions of medieval people in modern art, there are numerous saga museums in Iceland where visitors can see the sites of saga narratives and learn more about Iceland’s history. Many places in Iceland bear the same names they did in the medieval period, and so the events of the sagas can be carefully traced. You can even go on a saga tour!