What insights have you brought back as a result of this experience? How has your summer language study abroad changed your worldview? What advice would you give to someone who was applying for an SLA Grant or preparing to start their own summer language study? Did you meet your goals for language learning? How will you maintain, grow and/or apply what you have learned?

I was deeply impressed by the learning environment cultivated at Hebrew University. I had heard that the ulpan program was like a well-run ‘machine’ for mastering modern Hebrew. We spoke only Hebrew in the classroom for 5 hours a day and covered over half of the first year textbook in only about 5.5 weeks. I am not the first to say it, but there is truly no better way to learn a language than living in a society which speaks it. Through this experience, I accomplished my learning goals for this program and look forward to continuing with this language through personal study with tutors this year. By continuing to progress on my own, I plan to be ready for another ulpan next summer at the ‘bet’ level.

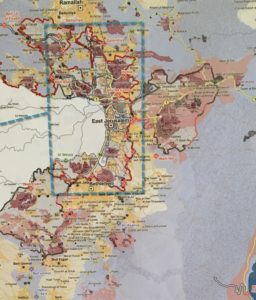

Interestingly, Hebrew came more easily to me than I had anticipated. I was worried that I might face the same challenges I have experienced in the past to learning Arabic–a language that I can easily admit is the hardest thing I have ever studied. However, it was because of my studies in Arabic that Hebrew came so easily to me this summer. They share many words such as day, “yowm”, and many similar roots, such as sun, “shems” in Arabic or “shemesh” in Hebrew. These similarities would seem to make it easier for Israelis and Palestinians to learn each other’s languages (both official languages of the state of Israel). However, the politics of the conflict have greatly hindered this possibility. Neither of my Hebrew teachers knew Arabic despite the growing number of Arabic-speaking students entering the university. However, one informed me that she is now ready to learn Arabic to help these students and explained that now she regrets not learning it when she had the chance in school.

While English can get you pretty far in both Israeli and Palestinian areas, after a summer of travel in this region, I am now more convinced than ever that learning both of these languages is crucial to understanding the complexity of this conflict by allowing the inhabitants of this land to express themselves in their own voice, in their own languages. Language acquisition is the first step for me to be able to research and write a truly transnational dissertation of the United States and Israel-Palestine–one in which I share a convincing portrait of two societies, not just an in depth study of the U.S. intervening unidirectionally into Israeli and Palestinian affairs but a study of interactions moving multidirectionally back and forth across the Atlantic.

During the last week of the program, I was out celebrating with my classmates. I ended up meeting and chatting with two young Israelis. Much to my surprise, I learned that I was in conversation with a male IDF soldier and a female police officer. While I had seen soldiers on and off duty all around all summer, I had never made an effort to speak to any of them. I did my best to listen to their stories, asking if they felt safe in their work. The young woman told me, “Hardly ever.” Suddenly, she leaned in and said, “Why do Americans hate us? I feel like we are so vilified, and no one wants to understand our side of the story.” I had many things I was thinking and feeling: Over the course of the summer, I had seen inequality and injustice at work through more and less visible systems of oppression. I could see that there were more than just ‘two sides’ to this conflict, but I could not deny a series of power imbalances between the Israeli and Palestinian ‘sides’. I was also struggling to account for American ‘power’ to influence this region; I had after all had the privilege to travel both in and out of Israeli and West Bank territories throughout the summer, more freely than either most Israelis and Palestinians, because of my U.S. passport. I also worried that I had allowed my critiques of certain aspects of Israeli policies to blindly bias me against IDF soldiers and police officer writ large…I am sure many of these thoughts flitted through my head at the time, but as I looked into the brown eyes imploring me to understand her side in all of this, all I could say in that moment was, “I promise to tale your story back with me and share it.”

For others who pursue the SLA Grant experience, I encourage you to prepare yourself for a dose of self-reflection. What does it mean to be an American in the place of the world where you study? What privileges as an American allow you to be live there and learn there? Given this degree of ‘power’ for just being a U.S. citizen, how will you harness your privilege while you are there and when you return home? For me, my goal is to share stories: stories that have been silenced or overlooked in American popular and academic assessments of the ‘Israel-Palestine conflict’, stories that add layers of humanity and complexity–as well as thoughtful critique and insight–to an otherwise ‘two-sided’ dominant narrative.

will always stand up for themselves and fight, even to the death, for the right to live here “freely”. Like all nationalist tales, it is not clear whether such stories can contribute to peace with minorities in the region.

will always stand up for themselves and fight, even to the death, for the right to live here “freely”. Like all nationalist tales, it is not clear whether such stories can contribute to peace with minorities in the region. the lowest place on earth, snuggly surrounded by the Negev Desert on one side and the mountains of Jordan on the other. It is best to visit the Dead Sea in the winter as opposed to the summer months; however, while the locals are smart enough to avoid the heat, this does not stop plenty of foreign tourists risking the sun and temperatures over 110 degrees Fahrenheit. The water was so warm it felt like bathwater, and we only survived in it for about 30 minutes. However, the mud was still great–best free exfoliant a girl can get! And of course, there is nothing quite like floating effortlessly in the Dead Sea.

the lowest place on earth, snuggly surrounded by the Negev Desert on one side and the mountains of Jordan on the other. It is best to visit the Dead Sea in the winter as opposed to the summer months; however, while the locals are smart enough to avoid the heat, this does not stop plenty of foreign tourists risking the sun and temperatures over 110 degrees Fahrenheit. The water was so warm it felt like bathwater, and we only survived in it for about 30 minutes. However, the mud was still great–best free exfoliant a girl can get! And of course, there is nothing quite like floating effortlessly in the Dead Sea. It seems impossible that anything could be green in the middle of the vast, endless Negev Desert. However, the Ein Gedi is an ancient spring that has kept the Bedouin tribes of this region able to dwell and survive here for hundreds of years. The Israeli state control of this spring for tourism has, of course, caused problems for these tribes. Keeping in mind these politics, we hiked a path cutting through the mountainsides, stopping to cool off by wading in waterfalls along the path. The water felt unbelievably refreshing in the summer heat!

It seems impossible that anything could be green in the middle of the vast, endless Negev Desert. However, the Ein Gedi is an ancient spring that has kept the Bedouin tribes of this region able to dwell and survive here for hundreds of years. The Israeli state control of this spring for tourism has, of course, caused problems for these tribes. Keeping in mind these politics, we hiked a path cutting through the mountainsides, stopping to cool off by wading in waterfalls along the path. The water felt unbelievably refreshing in the summer heat!

modern churches dedicated to aspects of Jesus’s ministry that constitute only ‘possible’ locations for where events in Jesus’s life might have taken place. One such church is the Church of the Beatitudes built by the Roman Catholic Church between 1936-1938 in honor of Jesus’s teaching of the ‘Sermon on the Mount’. While it is unclear whether this is the exact hill where Jesus would have delivered this sermon, it is said that Christians have paid homage to this area since at least the 4th century.Whether it is this hill or the next one over, the church and grounds are really beautiful. You cannot help but reflect on Jesus’s words as you look out onto the hills and the Sea of Galilee.

modern churches dedicated to aspects of Jesus’s ministry that constitute only ‘possible’ locations for where events in Jesus’s life might have taken place. One such church is the Church of the Beatitudes built by the Roman Catholic Church between 1936-1938 in honor of Jesus’s teaching of the ‘Sermon on the Mount’. While it is unclear whether this is the exact hill where Jesus would have delivered this sermon, it is said that Christians have paid homage to this area since at least the 4th century.Whether it is this hill or the next one over, the church and grounds are really beautiful. You cannot help but reflect on Jesus’s words as you look out onto the hills and the Sea of Galilee. I can best use my power and privilege for good (and what the ‘good’ here even means). A few words have encouraged me along the way this summer: “

I can best use my power and privilege for good (and what the ‘good’ here even means). A few words have encouraged me along the way this summer: “

objects within the shrine itself since it is just a place for personal prayer and meditation. There are beautiful statues of peacocks and hawks as well as star patterns throughout the gardens but these have no religious significance. The Baha’i emphasize beauty through symmetry as a means of preparing oneself for prayer. They do pray in the direction of Acre, where the prophet Baha’u’llah is buried.

objects within the shrine itself since it is just a place for personal prayer and meditation. There are beautiful statues of peacocks and hawks as well as star patterns throughout the gardens but these have no religious significance. The Baha’i emphasize beauty through symmetry as a means of preparing oneself for prayer. They do pray in the direction of Acre, where the prophet Baha’u’llah is buried.