One of the strongest memories of my time in Munich this summer is that of my visit to the Dachau concentration camp. The concentration camp lies just outside the city of Munich and next to the Dachau Schloss, the beauty of which is unfortunately often overshadowed by the presence of the Nazi concentration camp.

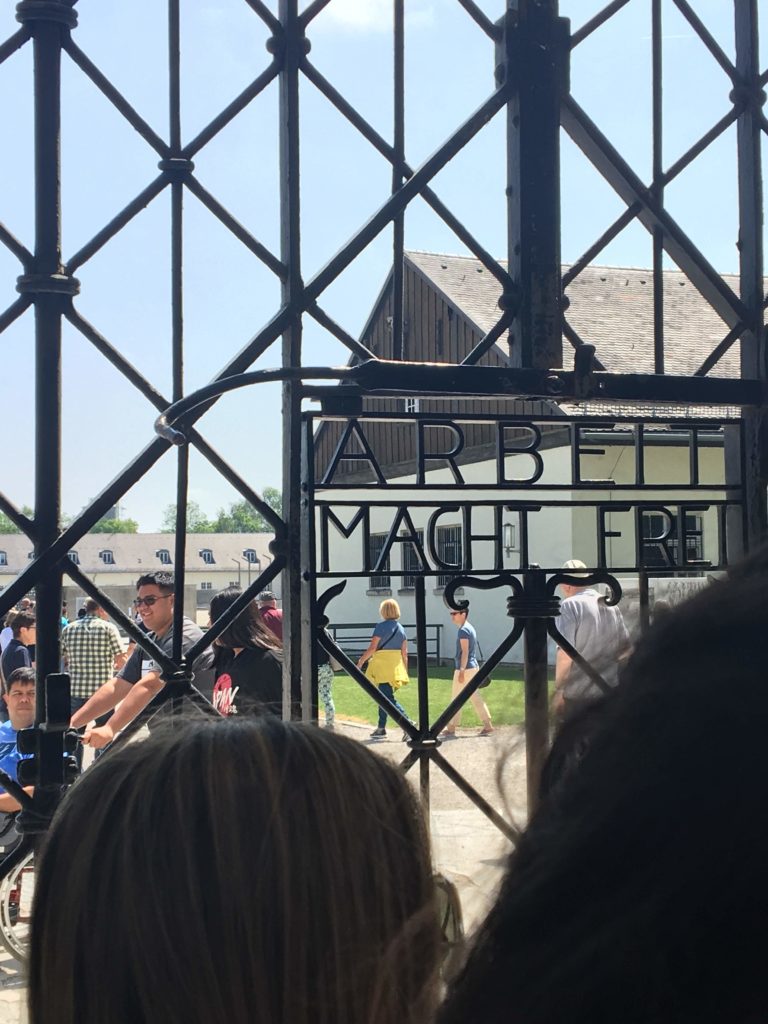

I participated in a group tour led by a German tour guide, and we arrived at the entrance of the Dachau concentration camp after an hour-long train and bus ride from Marienplatz. Dachau was the first concentration camp the Nazi regime built and at first held political prisoners as captives. Dachau was not an extermination camp like Auschwitz. However, the words on the gate welcoming the new victims hinted at a no better future:

“Arbeit macht frei,” or “Labor will free you.” These delusory words gave the prisoners entering Dachau a false hope that they may be released if they work hard. In reality, the words meant that death by labor was the only way of escape, and the painful irony was only followed by the desolate landscape of the camp.

Walking through the Dachau facilities preserved from the time of World War II, the tour guide explained to us that as Dachau began to imprison a broader range of population – including Jews, Jehovah’s witnesses, Catholic priests, and homosexuals – the Nazi officers developed a very intricate system of labels to categorize and assign to every prisoner.

The 20-minute documentary film we watched gave us a more detailed look into the atrocities done at Dachau The prisoners were subject to absurdly strict or haphazard rules by the Nazi officers and, as a result, received harsh punishments that often lead to death. Not unreasonably, many prisoners chose to commit suicide by throwing themselves to electric fences or deliberately crossing the boundaries of the Dachau, which forced the guards to shoot them.

Lastly, we visited the crematorium, which was used to burn all the corpses in the camp. The guide told us that towards the end of the war, Dachau did not have enough coal to burn all the corpses, so endless piles of corpses just lay outside of the crematorium for weeks.

The visit to Dachau was full of intense emotions. It is quite remarkable and commendable that a visit to a concentration camp is a requirement for all German schools – a show of the culture of remembrance, die Erinnerungskultur, in Germany. The reason must be that Dachau is not simply a historical artifact. Rather, in this age of ever-increasing hatred and discrimination where the geist of National Socialism still lurks around and haunts us, Dachau sends a strong message to us that is summed up in this epitaph of this statue:

“Den Toten zur Ehr, Den Lebenden zur Mahnung”

Honor to the dead, and warning to the living