And we’re back with another (hopefully) informative blog post! As promised, I’ll be discussing three experiences with traditional Japanese culture. I visited a Zen Buddhist temple and learned a little bit of calligraphy thanks to the hard work of the ICU staff. Afterwards, I had the chance to buy myself a yukata and put it on for a festival in Asakusa. All three experiences were very enlightening in their own way, though the third had its difficulties. Without further ado, let’s get right into it.

Sakae Miayama Temple

My first cultural excursion was a trip to Sakae Miyama Konanin to learn about Zen Buddhism.

When we entered we were met with temple staff (one of which was an ICU alumnus) and the head priest who currently oversees the temple as the 29th member of the temple’s lineage of priests. My first impression of him in his ceremonial robes was, of course, that he was about as traditionally Japanese as a person could be. He was exactly what you would expect a Buddhist priest to look like from the rounded spectacles on his face down to his sandals. All of the staff members spoke primarily Japanese, but the ICU alumnus and our guide, Asaoka-sensei, translated nearly all of the information given to us.

The monks of the temple where kind enough to offer more than a simple tour of the temple. They also introduced us to Zen philosophy, history, ceremonial traditions, meditation techniques, and etiquette. We were essentially treated to a crash course for Zen Buddhism. Unfortunately due to temporal distance and losing my informational booklet on the train, I’ve forgotten the finer points of our history lesson. Nonetheless, I’ll do my best to recount what I learned before getting into the more practical experience.

My general take away from our lesson on Zen philosophy was mindfulness, efficiency, and unity. In the sect of Zen Buddhism the temple adhered to (whose name I have forgotten entirely) many aspects of one’s daily life are regimented in order to be as efficient as possible without indulging in excess or wastefulness. The methods that one uses for daily life also imbue a sense of connection and equality with those around them. This was most easily demonstrated to us through Zen dining etiquette.

There are well defined and rather strict rules regarding how to eat in the temple. In the picture above you can see a spoon, a pair of chopsticks, a cloth, a stick, and bowls of varying sizes. All of these items with the exception of the plate of fruit and bowl underneath it come in a compact package. The bowls come stacked together with the utensils and cloths wrapped on top in a specific manner. You unwrap things in a certain order. You set your table in a certain order. You put everything in a certain place. Each item has an express, single purpose. Once you have finished eating, you put things back in a certain order. All of this is to ensure efficiency. The method we were taught is intended to be the most streamlined way to eat that wastes no time, effort, or food.

On top of these strict set of rules is behavioral etiquette. Whenever you eat you have to be sure to avoid pointing your utensils away from yourself. Always bring your food inward. There is no speaking during meal time. Other monks of the temple will pass by and bring each food item in pots and buckets and dispense them to you. Rather than verbally telling them to stop, there are certain hand gestures you can use. Whenever the servers arrive or leave, you both bow to one another. Each of these points is meant to teach you to be mindful of yourself and to respect those around you. You are all equal in sharing a meal, an essential part of life itself. No one is above the other, and the self should be diminished in favor of honoring and maintaining a harmonious collective.

Pretty heavy stuff for dinner, I know. It sounds a lot better coming from a Buddhist priest speaking Japanese.

Dining etiquette was what we spent the most time on for the reasons I mentioned above. It was an efficient way to teach us fundamental facets of Zen Buddhism. Of course, we also meditated. We were taught the proper posture, but there was much less time spent on teaching meditation techniques. I enjoyed the silent, serene atmosphere set by wonderful incense and an opening chant. I honestly just daydreamed the entire time, so there isn’t much to say about this part of the experience.

After dinner and meditation, we ended the session with a casual tea ceremony. One of my favorite parts of this experience was the head priest. He was a very approachable and funny 70 year old man who didn’t look a day over 50. You could tell that he enjoyed teaching his philosophy to inquisitive foreigners, and he did his best to use simple Japanese and even English at times. He was adamant about etiquette without being too austere in correcting mistakes. I enjoyed having him as our teacher for the evening.

Calligraphy

Calligraphy is a Japanese art that was adopted from China centuries ago. In modern Japan it is a cultural practice only used on special occasions such as New Years greetings and signing into a wedding ceremony. It’s an art not many people are adept at, but all Japanese students who attend middle school have at least a few classes in calligraphy. Most Japanese people don’t study calligraphy beyond that, but others choose to continue studying while some become so adept that they make a living from it.

Our quick introduction to calligraphy didn’t give anyone enough experience to call themselves masters, but it was fun nonetheless. I always thought calligraphy of any type was incredible but probably not too difficult to pick up. I was so very wrong. Calligraphy really is an art. It’s easy for me to write legibly in Japanese. It’s not even all that hard to have good looking handwriting. However, there are rules to calligraphy. The brush was surprisingly difficult to handle, and producing the shapes you want was much harder with ink that I anticipated.

Calligraphy in Japanese and Chinese demands a few things: symmetry, proper proportions, and recognizable strokes. Everyone has their own style, to some extent, but certain techniques have to be mastered by all who have set their minds to learning the art. These techniques aren’t too hard to accomplish with a pen and paper, but it becomes far more nuanced and difficult to accomplish with a brush.

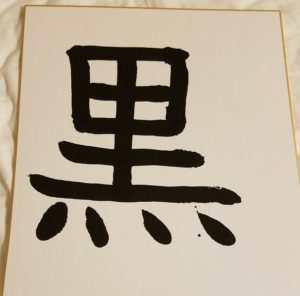

My classmates and I practiced the basic strokes and then chose a single kanji (a written symbol with its own meaning) to write on our own. During this process the previously mentioned Asaoka-sensei, a nearly professional-grade calligrapher, was teaching us. Before I attempted to draw my chosen kanji, I asked Asaoka-sensei to draw me a model.

I chose the kanji depicted on the right “kuro,” meaning black. I rather like the look of kuro, but I chose it because I figured the straight lines would be easier to write. I was right for the most part, but the edges of the lines are what were difficult to reproduce. You can see that Asaoka-sensei’s work is tapered with rounded ends. The strokes are also very smooth. My attempt was… Less elegant in comparison.

So if we were to critique my work, the first noticeable problem is with symmetry. The kanji isn’t in the center of the paper. The proportions of box at the top of the symbol are a bit off as they should be more tapered. I could keep going, but I’ll spare you all the critical scrutiny. All this is to say that calligraphy is something that is mastered through mindfulness and practice. If given more time and the resources, I would love to continue learning in whatever free time I could muster.

Wearing a Yukata

A yukata is a simpler, summertime kimono typically made of more breathable cloth. In modern Japan yukata are worn to summer festivals and other special occasions. Though yukata have less layers than kimono, they still have multiple pieces to them. There is the yukata itself which is the robe-like dress, strings to tie things in place, a decorative sash laid over the strings called an obi, and, typically, traditional shoes called geta. I managed to find my yukata and obi for a very reasonable price, but my feet are a bit too large to fit into geta. Large footed foreigners beware.

Disappointing shoe sizes aside, putting on my yukata went quite well. I managed to do so on my own, and I think it turned out quite well. The sandals I brought with me looked good enough with the ensemble, and I found out that it’s fairly common for Japanese men and women to were western sandals to festivals.

My friends and I attempted to go to a fireworks festival in Asakusa while in our yukata. Unfortunately, it rained. Heavily. And because the festival is so very popular, it was incredibly crowded. I don’t think I can accurately put into words exactly how crowded it was. Saying that people were packed together like sardines doesn’t do the situation justice. Saying that something around a million people were gathered in a single section of the city doesn’t do the situation justice. Saying that there were police officers directing pedestrian traffic and taping off certain paths while occasionally pushing people into place doesn’t do the situation justice. It was… A lot to handle in an outfit that restricts your movement a fair amount.

I could lament further, but I think you all get the point. While the festival was a bust, wearing a yukata for the day was actually really fun. The fabric is very breathable, so even though I had an outfit on underneath I never got too hot. It also dries very quickly, which was wonderful consolation prize after we escaped Asakusa. Despite it’s someone restrictive nature and the unfortunate circumstances that occurred while I was wearing it, I became so enamored with my yukata that I have felt the urge to buy myself another ever since. If I had space in my luggage, I would definitely have picked up another. They’re simply beautiful.

Next Time

Each cultural experience was honestly amazing to me. I know this post drags on a bit since I rambled on about each one, but I think that simply reflects how exciting each moment was. I hope my enthusiasm came across in my description of each event.

But enough about that. On to the next thing. I plan to use my next two posts to give some impressions I’ve developed about Tokyo as time has gone on. The topics will be a bit scattered, so I can’t really think of a good way to summarize them at the moment. Still, look forward to the next rambling post I come up with.