Dear reader,

Today’s installment has two parts. I took a tour of the Amalfi coast yesterday, which means that you are in for another travel edition with lots of pictures and fun facts. However, I first want to tell you about some conversations I had this week about the immigration crisis in Europe. These conversations provided substantial insight into modern Italy and are worth sharing. However, they deal with international politics and not pictures, so feel free to skip to the second part if you want.

Part 1: Italians’ views on the immigration crisis

As many of you know, there have been staggering numbers of migrants moving from North Africa and the Middle East to Europe. The question of how Europe should respond to these migrants is especially relevant in Italy. By nature of its location between North Africa and the rest of Europe, Italy is often the place where these migrants first land. The dilemma is this (I simplify greatly): on the one hand, receiving so many destitute people is a severe strain on Italy’s resources, but on the other hand, both international law and human compassion would forbid turning the migrants away.

This week, I asked two Italians for their opinion on the migrant crisis. I now present to you what they said to me. (I must add a disclaimer that this situation is very current and changing every day. Furthermore, I have not been keeping tabs on the EU’s immigration policies, so forgive me if I oversimplify or misrepresent such an important situation.)

The first person I asked was the Italian woman with whom I have been meeting to practice my Italian speaking skills. Her reply was this: to her, Italy is a beautiful country, full of humanity, goodness, and creativity. It is also a place that suffers under many evils, like the mafia and the growth of poverty. In the end, however, human life takes first priority over other concerns. Italy cannot refuse to help the desperate people fleeing their homes in search of a more just society.

The second person I asked was my literature professor from Sant’Anna. His response was much longer and more detailed.

First, he is frustrated by the EU’s current policies, which make it very difficult for migrants to move from one European country to another. The migrants that land in Italy are treated as Italy’s concern, not Europe’s concern. According to him, this places an unfair burden on Italy, especially when most migrants want to use Italy only as a gate to France and Germany where the jobs are. Finding themselves stuck in a country without a job market, it’s no wonder that some migrants become desperate and turn to crime to provide for themselves.

However, he is even more frustrated by the new Italian government’s attempts to fix the problem by closing all the ports. First, this policy places Italy in opposition to the EU. Second, the closed-port policy means that migrant ships, even those in need, are turned away from Italy. This has caused the death of many people. Thirdly according to him, the policy is ineffective. International law requires that if a ship sends out an SOS signal in international waters, it must be rescued. This means that hundreds of migrants are still arriving in Italy after being rescued by the military.

My professor shared that this situation has brought to light his frustration with the EU in general. According to him, European bureaucracy is “the Inferno.” He believes that Italy will receive sanctions from the EU for closing its ports, but it will take months. He said, “Imagine if Florida closed its ports. It would receive retaliation from the US government within hours!” In fact, his dream is for Europe to become more like America: united states with a stronger central government based on human rights.

Furthermore, he is deeply concerned at the trends of isolationism, nationalism, and xenophobia that led Italy to close its ports. According to him, these trends bear an eerie resemblance to Fascism. One hundred years ago, the Jew was excluded from society; today, it is the migrant who is unwelcome. He said, “This is not the Italy that I know.”

However, when I asked him what the majority of Italians thought, he replied that Italy was split 50-50 on these issues. Clearly, plenty Italians believe that “Strong Italy” means “Italy First”; otherwise, the current government would not be in power. Therefore, the opinions of the two Italians to whom I spoke are by no means indicative of the country as a whole. However, I learned a lot about Italy even by only hearing one side of the story. The passion with which both my professor and my speaking companion gave me their opinions on this issue showed just how much it matters to them.

Part 2: The Amalfi Coast

As I said at the beginning, I went on a tour of the Amalfi coast yesterday with a very knowledgeable tour guide. Here are some of the pictures and fun facts I picked up along the way.

Electricity is very expensive in Italy because Italy can’t produce enough of it for all of its inhabitants. This was not always the case. Italy used to use nuclear power plants; however, after Chernobyl, it shut down those power plants, and to this day has not made up the difference. The expense of electricity means that Italians don’t use air conditioning, central heating, or drying machines. They also have to be careful not to use too many big electrical items (the oven, the iron, hair dryers, etc) at once.

Even though electricity is expensive, churches still use electric lights instead of much cheaper wax candles. This is because they have learned that the smoke from the candles damages the art in the churches. The pictures on the ceiling of the crypt of the Cathedral in Amalfi (see below) were almost entirely blackened until just recently when they were cleaned.

Churches in Italy were built at all different times and in all different styles. However, most of them have been renovated in a grand, ornate style (called “Baroque”, a style which was popular during the Catholic Counterreformation. My new hypothesis is that many churches were renovated around this time as part of the Church’s attempt to “change its look” in response to the Protestant Reformation. This would explain why many churches in Italy look so similar.) The Cathedral in Amalfi is one such church. Restorers have exposed one of the old Roman columns which was first used to build the church in the 8th century and then was subsequently sheathed in the grand marble towers used by the Baroque.

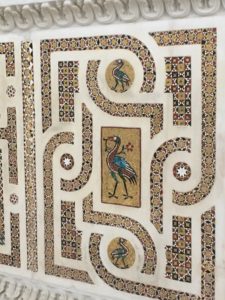

The Amalfi Coast used to make its money not by tourism but by sea-trade. This meant that this area of Italy had lots of interaction with the Arab world of North Africa. For that reason, one can see some Islamic influence in their art.

Being close to North Africa also meant the danger of Arab pirate raids. This picture tells the story of a storm that miraculously appeared and destroyed the ships of approaching pirates.

Finally, we saw a chapel built to hold a vessel of the blood of an early Christian martyr, Saint Pantaleon.

According to the Italians, every year, on the anniversary of his death, the blood (long since congealed) miraculously liquefies.

In America, I believe, many people, even believing Catholics, would treat such phenomena with skepticism and a little revulsion. However, many people in Italy still fervently believe in the power of relics and in such miracles as these.

In all, there’s a reason that the Amalfi coast is so famous. It is one of the most beautiful places I have ever been.

(For more views of the natural beauty of the Amalfi coast, look at my pictures from “Il Terzo” of the Path of the Gods, which runs along the coast. It was well worth it to go back just for the views from the highway.)

Until next time,

Beatrice