I am now only two weeks out from returning back to the States. It is remarkable how my time in Jordan has flown by. Because of my tight schedule, I have started to pack it with as much activity as possible!

One of these activities was attending Jordan Food Week (أسبوع المأكولات الاردني) at the Ras al Ain Hanger. It is a brand food festival in Amman that celebrates culinary traditions from around Jordan, featuring different restaurants and food stuffs vendors. My friends and I were keen to try as much food as possible before selecting a place for dinner and feasting. I ended up eating a delicious wrap of fried haloumi cheese with a spicy molasses sauce and a delicious fig salad with homemade cheese. The real highlight though was the dessert: fatira sultia (فطيرة سلطية). Made of shredded filo dough covered in butter (ghee was used in our dessert instead), cinnamon sugar, and pistachios, the smooth buttery dessert was surprisingly not as sweet as it sounds. In my opinion it was one of the best foods I have had while in Jordan.

One of my friends from my language institute is a big “disc” guy (aka ultimate frisbee but we’re politically correct here) and had joined a local club in Amman. He had been encouraging people to go for the last few weeks, and this week I finally went. While I hardly would call myself good at ultimate (or even have any experience) it was a great opportunity to get out and meet some new people. There was a great mix of summer students like us, expats who played, and local Jordanians who liked the disc life. I fully intend to keep attending over the next two weeks, as playing some ultimate with Jordanians was a really fun experience!

I have not mentioned this much in my blog, but this is actually my second trip to Jordan (my first being last summer for a whopping three days stuck onto a trip to Palestine). So far, I had only revisited one place (the Amman Citadel – spot Week 1) on my journey; however, I felt incredibly obliged to return to two of Jordan’s most famed and beautiful sites: Petra and Wadi Rum.

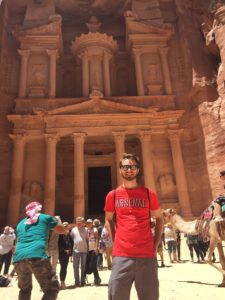

I’ll keep my Petra comments brief, as I personally believe that even as magnificent as Petra is, once you’ve seen Petra once you’ve seen it. It was incredibly fun to have a second hike down the entrance siq (valley), gaze up at the Treasury, and ride a donkey up to the monastery at the far end of the site. However, I would rather focus on what I would consider to be Jordan’s most incredible experience: Wadi Rum.

Wadi Rum is Jordan’s magnificent desert area situated only about thirty miles from the Saudi border in the south. It is characterized by red sand and incredible rock formations. The site is so non-Earth like that pretty much any movie pertaining to Mars is filmed there (including The Martianfeaturing Matt Damon). The magic of Wadi Rum is that regardless of how many times you go, you will always see something different: there’s always a new dune to roll down, or new rock to climb, or a new camp to spend the evening in. I was as blown away – if not more – on my second trip to Wadi Rum than on my first.

Of course, I made sure I took part in the classic activities. Any trip to Wadi Rum without a camel ride is a waste of time in my opinion – also because I love riding camels! And you have to dangerously climb up at least one rock formation and one dune. And without a proper sunset spot to watch a sunset, you truly cannot say you’ve been to Wadi Rum! I also happened to luck out: a lunar eclipse happened at roughly 10:30 PM on the night of my stay in Wadi Rum. While star gazing is a classic Wadi Rum activity, the red moon dimmed the sky enabling one to see more stars that you could ever imagine.

While Wadi Rum is technically a nature reserve, it is impossible to talk about the site without discussing the indigenous people: the Bedouins. In Jordan, there are three types of people. First there are the mediny (مدني) – those from the cities. The overwhelming majority of Jordanians are medinymostly because Amman’s population constitutes over half the country’s total population. Then there are the fellahior villagers. These people usually live in the North in the smaller towns on the outskirts of the metropolitan areas of Jerash and Irbid (spot my past posts for some discussion of Jerash and Irbid). Then there are the bedowy (بدوي) or Bedouins who reside mainly in the deserts of the South.

The treatment of Bedouins have always been a major question within the country of Jordan. Historically, Bedouins and their tribes were the only people truly settled in the modern state of Jordan. The tribes were nomadic and lived in tents. To this day, they wear a traditional robe called a deshdajah and often wear a keffiyeh head scarf. Because of this conservative tribal culture, most mediny possess a number of stereotypes about Bedouins (mostly the facts I have just listed). As a result, many look down on the Bedouins and some even fail to consider them in forming their opinions on the country of Jordan.

While in Wadi Rum, I got to stay in a tent at a Bedouin camp. I hoped to learn more about their culture and their opinions on their relationship with the country of Jordan. After returning from a day of touring the impressive rock formations, we were treated to a meal called zarba(زرب) which refers to anything cooked with coals underground (kind of like a Polynesian-style pig roast). While pescatarian me could not take advantage of the meat, the smoked vegetables along with a wide array of Middle Eastern salads were delectable.

After sitting listening to a local Bedouin play the oud – a classical guitar-like Middle Eastern instrument – we had the opportunity to talk with the owner of the camp. He told us a story or two talking about the culture of the Bedouin. Interestingly, the Bedouins talk more like Saudis than Jordanians; as a result, their spoken Arabic resembles fusha, meaning I could understand and converse with the locals far easier than I would with a mediny in Amman. I made sure I took advantage of this ability to communicate to ask a few questions.

The owner – Suleyman – told us about his life story. He had served in the Jordanian special forces before coming back to Wadi Rum. Along the way he had married a villager from outside of Irbid – an rare and almost forbidden love. He answered my questions describing the immense respect he had for King Abdullah and the Jordanian government. Over the last few years, the government has invested in projects to help improve the standard of life for Bedouins in the desert. This has involved building houses, hospitals and schools in the village at Wadi Rum. While he said he misses the old life, he acknowledges that it will be better for his children. His eldest daughter had just left to study medicine in Irbid (way up north) and hopefully become the first doctor from the tribe of Wadi Rum.

Many Bedouins have ties to Saudi Arabia or even nationality, as their tribes often stretch over the nearby European-made border. Suleyman’s tribe is originally from Mada’in Saleh, an ancient Nabataean city in Saudi Arabia (considered the Petra of Saudi Arabia). He has extensive family over the border and has a visa that enables him to enter and exit Saudi Arabia freely. I asked him if he and his tribe felt more Saudi or Jordanian. He said “Definitely Jordanian”. He explained about the generosity and benevolence provided from the Jordanian monarchy, and how from the start of the country of Jordan Bedouins have been accepted by the government – even if society felt differently. He compared that to his family who live in Saudi Arabia, where the government feels little need to aid the Bedouins. The level of poverty there far exceeds that of Jordan, as the government really only cares about the major cities and not the rural communities.

While Suleyman described the relationship between the government and Bedouins to be pretty rosy, historically this is not always the case. The major tourist site of Petra is a great example of this. A tribe that Suleyman described as Bedoun (بدون) or “Without” in English moved into Petra and lived in its caves. These people do not have the same value base as other Bedouins, and most would consider these people to be lacking the hospitality of true Bedouins. When the Kingdom of Jordan sought to develop Petra as tourist site, the King expelled the residents of Petra. However, as they had no where to go, they continued to live among the ancient facades, often times desecrating the antiquities. As a result, the government allowed the locals to work at the site, mainly leading donkeys and camels or running souvenir stands. The king built a series of apartments nearby to the site so that the locals still had a place to live. By 1990, no people lived among the facades.

I asked my tour guide about whether he felt the government had overstepped their bounds. He seemed to think that the governments policy was fair especially given their generosity in building homes for the people, and that the locals of Petra were doing more to damage the site than anything else. However, while on a donkey up to the enormous monastery at the top of a mountain, I asked the little kid guiding the donkey if he was from “Here in Wadi Musa” (Wadi Musa being the major town about two kilometers away from Petra). His response was “No, from here in Petra”. While the population has been relocated, they still view Petra as “their place” and as a result often run the tourist activities past the main gate mafia style.

After a fun weekend in the South, I have a better understanding of the riff between the mediny and the bedowy. While the government has treated the bedowy kindly and respectfully, there is still a divide between the two groups. That said, it is impossible to talk about the Kingdom of Jordan without talking about the Bedouins. There are an integral part of Jordanian society and culture, and with the government’s protection, they should continue to fill this roll.

Thank you to all who have put up with my writing for the last few weeks. I have a few more posts coming your way before I’m back in the Bend so be on the lookout!