In this next installment of our Alumni Interview Series, I got the privilege of asking Stephanie Guerra (2004) a few questions about the craft of writing, her work teaching in the King County Correctional Facility, and managing her hectic life with the need to write.

In this next installment of our Alumni Interview Series, I got the privilege of asking Stephanie Guerra (2004) a few questions about the craft of writing, her work teaching in the King County Correctional Facility, and managing her hectic life with the need to write.

Can you briefly describe how you discovered you wanted to be a writer?

I’ve always loved to write. Two childhood experiences had special influence. The first was when my dad became interested in Aztecs and brought home some great illustrated nonfiction books for kids. I was in third grade, and I was so enthralled by Aztec culture that I tried to write a novel about an Aztec princess whose lover was slated to become a human sacrifice. I got thirty pages in, and that taste of novel-writing stuck with me. Then in fourth grade, my teacher, Mrs. Seagal, called me an “authoress” and stayed after school regularly to host a small writing workshop for another student and me. She made me believe that I could pursue writing in my adult life.

You teach creative writing to the female inmates at the King County Jail. What are some of the obstacles and the rewards that come along with the work?

I’ve actually expanded the program to include King County Juvenile Correctional Facility, so I’ve been working with teens lately as well. The greatest obstacle that comes with this work is the heaviness I carry when I hear my students’ tragic stories. Working with teens is especially hard. Many of them have been abused and trafficked, and it breaks my heart to read their work. But this teaching is also its own reward. I get to work with marvelous, interesting people who have powerful stories to tell. Many of them are talented writers and poets. I’ve been blown away over the years by the high quality poetry (especially rap) that some of them produce. It’s a pleasure to be at the vortex of an ongoing effort to make art without trying to sell it. There’s a strong therapeutic component as well. I’m not a therapist, and I’m very careful about offering advice, but the students really support each other in a way that resembles group therapy and it’s lovely to be part of that.

What format do you use with your students?

I don’t use a workshop format with my students. The turn-over is so high in jail and juvenile corrections that I don’t have enough time with students (either per class or over the course of months) to run effective workshops. Instead, each lesson must stand on its own. I’ve developed a literature-based writing program with a growing visual arts component. I begin sessions by reading excerpts from literature or sharing visual prompts which the students then use as springboards for their own writing. I scaffold them as they work (usually for twenty to thirty minutes), and at the end there’s time for sharing and comments. I don’t focus on correcting students’ work. We have such a short time together that I see this as a creative and emotional outlet for them, a writing community, and an affirmation that art can happen anywhere.

How has your experience thus far with your King County students affected your teaching at Seattle University?

At Seattle University, my students are pre-service and in-service k-12 teachers. My work with teens at the juvenile detention center brings a real-life dimension to my lectures and gives me evolving examples of teen writing to share with my college students. Teaching in corrections has also made me familiar with many types of behavioral problems and learning disabilities, and I can offer insights to my teaching students about the best ways to serve special needs populations.

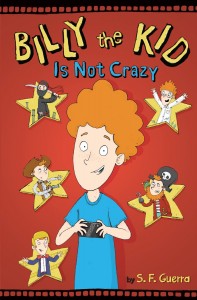

Switching gears a bit, you’ve got a new book–Music, Love, and Drugs–slated for publication in 2015. What was the inspiration for this book, and how have you found working with Amazon’s publishing outfit?

Music, Love & Drugs was a working title. The book, now called Betting Blind, and the sequel, Out of Aces, will be out in 2015. Both books were inspired by my youth in Las Vegas. I lived on my own at sixteen in a colorful, funny, sleazy, interesting city. It gave me a lot to write about. As for the question about Amazon, working with Amazon Children’s Publishing has been excellent. They bought my original publisher, Marshall Cavendish, in 2012, and the transition was smooth and positive. ACP is conscientious about timing of payments and responses to manuscripts; my editor has remained the same, and she’s a marvel; and ACP solicits a high level of feedback on design choices. I don’t think they’d use a cover that I disliked, for instance. They’re highly focused on author satisfaction.

Given all of your engagements, what’s your writing process like? Do you outline your works before drafting? Are you an early morning writer, or do inspirations come to you in the middle of the night?

I have two young children, so I write in snatches, and I’ve learned to draft mentally before putting words down. I do a lot of preliminary brainstor

What are you reading now? Would you recommend it? Why?ming by hand in notebooks and I draft on the computer. I write for several hours on weekdays while my youngest is in preschool and I write all day on Saturdays. It adds up to about fifteen hours a week. It doesn’t matter whether I’m inspired or not; I make myself write, and as I write, the inspiration comes.

I’m reading Dostoevsky’s Demons (called in other translations The Possessed). Dostoevsky amazes me with his ability to depict both the depths and heights of the human soul. His psychological insights are profound and often disturbing. He is my favorite author.

Lastly, what advice would you give a young writer that you haven’t heard anyone else tell you?

Don’t place so much focus on publication that you lose the joy in the writing process. Once you’re published, don’t get bogged down with promoting and business details and forget to enjoy this wonderful writing life. Finally, buy A Syllable of Water: Twenty Writers of Faith Reflect On Their Art for a series of essays that are grounding and buoying at the same time.

Cheers,

Dev