Kiswahili directions on a tree. Photo: Nyakeh Tuchscherer

One of the truly beautiful things about languages is that they have rich and sometimes surprising histories. This is true for so-called ‘dialects’ of languages too. Too often we fail to stop and think about the birth of various languages and how those languages spread to the regions they inhabit today. Kiswahili is a very interesting language historically, and there is wide debate on the historical and linguistic circumstances concerning its birth. This is due to the fact that many African peoples and languages as well as peoples and languages from outside the continent influenced the development of the language.

At its core, Kiswahili is an African language of the Bantu group. According to scholars,

“Swahili is a Bantu language, i.e. it belongs to the vast family of languages spoken South of a line stretching from the slopes of Mount Cameroun to the Northern shores of Lake Victoria, and thence towards the Coast, to Meru on the Eastern slopes of Mount Kenya (and further South, embracing the Southern group (Zulu, Xhosa, Shona etc.)” (Chimerah 1998:26 cited in Okombo & Muna 2017: 58). Citation below.

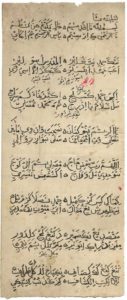

Kiswahili’s place of origin is along the eastern coast of Africa. It grew and spread. Much of the early Kiswahili literature was written in the Arabic script. Today it is a prominent language and lingua franca in Tanzania, Kenya, and many other places.

Al-Inkishafi. Kiswahili Islamic religious poem in Arabic script, ca. 1820. Citation below.

While indigenous Bantu languages provided the core for Kiswahili, what is also fascinating is the extent of outside influences on the language. Kiswahili uses many Arabic and English vocabulary words and verbs. In terms of Kiswahili words of Arabic origin, the most obvious example is the word ‘Sahil’ from Arabic which means ‘coast’. It is from this word that the name of the people, Swahili, comes from. The ‘Ki’ added to the beginning is the Bantu influence on the Arabic, as this prefix means ‘language’ (so ‘Kiswahili’ literally means ‘Language of Swahili people’). The Arabic influence came from the coast. Number words in Kiswahili combine Bantu origin one/’moja’, two/’mbili’, three/’tatu’, with those of Arabic origin like six/’sita’ and seven/’saba’. There are also many examples of Kiswahili phrases of Arabic origin, this being especially the case here in Zanzibar because the culture is predominantly Islamic. Even among non-Muslim Kiswahili speakers the Arabic/Islamic influence is everywhere, for example ‘Friday’ – the big Islamic prayer day all over the world – which in Arabic is ‘al-jumuʿah’, was transformed into the Kiswahili for ‘Friday’ as ‘Ijouma’. That means that Kiswahili speakers, regardless of what religion they practice, use the Arabic loan. While the influence from Arabic on Kiswahili is older, one can see many English examples in the language such as ‘hospital’ which was transformed into ‘hospitali’, and ‘doctor’ transformed into ‘daktari’. The English loans were through trade and of course British colonialism in places like Kenya and Tanzania.

One interesting final example is a Kiswahili word that entered the English language. Safari. While the word was originally from the Arabic ‘safar’ for ‘travel’, it didn’t enter the English language directly from Arabic, but rather from Kiswahili where it means ‘journey’ or ‘expedition.’

Notes

ibn ʻAlī ibn Nāṣir, Abdallah

1820 Al-Inkishafi

SOAS University of London Special Collections, Hichens Collection, MS 47770; see full information at https://digital.soas.ac.uk/LSMD000181/00001/citation). Image taken from https://blogs.soas.ac.uk/archives/2015/09/18/swahili-manuscripts-workshop/

Okombo, Patrick L. and Edwin Muna

2017 The International Status of Kiswahili: The Parameters of Braj Kachru’s Model of World Englishes. Africology: The Journal of Pan African Studies 10(7):55-67.