Name: Robert McKenna

E-mail: rmckenn2@nd.edu

Location of Study: Galway, Ireland

Program of Study: Dianchúrsa Míosa na nEachtrannach

Sponsors: Bob Berner & Joe Loughrey

A brief personal bio:

Dia duit! I’m Rob McKenna, a sophomore in the Irish Language and Literature minor from Richmond, Virginia. After three semesters of studying the Irish language, I’m off to Galway for a month to study in the Gaeltacht – the Irish-speaking region of Ireland. I’m also a cadet in the Army ROTC, and I’m active in the Glee Club.

Why this summer language abroad opportunity is important to me:

This grant is important because it will allow me to make a leap to the next level of competence in Irish. Only so much progress can be made in the classroom; to achieve my goals, I need to immerse myself in the Gaeltacht and get to a level of near-fluency. More importantly, Irish is a minority language, and because of that, it’s necessary to learn the language firsthand from the relatively few native speakers in the world. The more Irish is learned, appreciated and spread by non-native speakers, the longer it will survive.

What I hope to achieve as a result of this summer study abroad experience:

First and foremost, I want to become semi-fluent in Irish by the time I leave the program. This has been the object of my language study thus far, regardless of the actual language. At the very least, I want to be able to read and hear competently in Irish, to the point that I can read a newspaper or watch TV and understand what is being said. That being said, it’s important to have fun as well. Irish culture is rooted in music, dance and camaraderie, so I plan on partaking in all three as much as humanly possible.

My specific learning goals for language and intercultural learning this summer:

- By the end of the summer, I will be able to converse with native Irish speakers about current events and other matters of political, economic and social importance to the Gaeltacht.

- By the end of the summer, I will be able to carry on a casual conversation with native Irish speakers for up to a half hour.

- By the end of the summer, I will be able to acquire new vocabulary and integrate it into my working knowledge of the Irish language.

My plan for maximizing my international language learning experience:

I plan on abandoning my use of English, or B’arla, as soon as I arrive in the Gaeltacht. If I can’t understand something my host family is telling me, I won’t be the one to initiate English usage. In any and all cases, I will try my best to learn more Irish by using more Irish. If I go to the supermarket, I’ll point to things and ask what’s the word for them; if I read a magazine, I’ll ask what unfamiliar words mean; and so on. Most importantly, I will act as if this place is my new home, and I’ll try to adapt as best I can.

Reflective Journal Entry 1:

Given that I have three semesters of Irish language under my belt, it stands to reason that I would be half-competent in communicating. Not so at the moment. As it stands, I’ll be able to say ‘Dia duit’ (hello) and perhaps ‘Cen chaoi a bhfuil tú?’ (How are you?). My skills have rusted the two months I’ve been away from the language in Africa and elsewhere, as is evident when I listen to Irish language radio and understand almost none of it.

Does this worry me? A little, perhaps. But I’m not one to let worry dull my sense of optimism. I believe that even though the first week or so living with an Irish-speaking family and taking a class taught in Irish will be difficult, the benefits I can reap from the next month of study will far outweigh the hassles, or so I’ve been told. God willing, this will be a great month.

On the other hand, I don’t really know a lot about this place. I’ve seen it on maps, read about it, met a couple of people from the area, but never really had a taste of the life. I find myself wondering about particulars: what will it smell like? What’s the weather really like in summer? What does the earth feel like when you break it in your hand? Most importantly, will the people be accepting of my effort to learn their language? I believe they will; it’s been my experience with many foreign languages that the native speakers appreciate an honest effort at speaking it when abroad.

Anyway, back to not understanding Ráidio na Gaeltachta.

Sláinte.

Reflective Journal Entry 2:

The first week was a trip, as I suspected it would be. After all the trouble it took to get out here to the Conemara Gaeltacht, it feels as if I’m truly at the edge of the Western world. I’m not far off; I learned a short while ago that the name of the island is believed to be derived from some Indo-European root word for ‘west.’ The ancients were probably fully aware of where this island was in comparison to the rest of Europe.

I digress. Irish is very alive in An Cheathrua Rua, as most signs are written ‘as Gaeilge,’ but it exists side by side with English since the past two generations were taught both languages in school. While this allows a little security when I can’t find the words, it is frustrating when people don’t bother to speak Irish to us students. Because they are used to tourists, they often speak in English even when we initiate conversations in Irish. It’s getting better as they start to recognize us as students of the language, so hopefully we’ll be having full conversations ‘gan Bearlá’ with the locals by the time we leave.

Classes and my homestay have been great thus far. Being in a classroom and a house where hardly any English is spoken has helped me not only reclaim the knowledge I acquired the past three semesters, but also to quickly acquire and process a wide range of new words, structures and idioms. It has been a great challenge so far, but it’s a lot of fun too. I wouldn’t be doing this in the first place if it wasn’t fun, naturally.

It’s a beautiful, sunny day in Ireland, so I’m not going to spend any more time wasting it indoors.

Sláinte.

Reflective Journal Entry 3:

Yes, I’m not lucky, I’m blessed. Here I am in the west of Ireland, first and greatest of the Gaeltachts, learning the language every day. After two solid weeks of asking people to speak níos maille (slower) and to repeat themselves, my conversations are beginning to flow much better. I’m getting the same grammar I’ve already been taught, but taught now in greater depth and as Gaeilge. Although my skills are eclipsed by about half the class, I’m improving, and that’s why I came here.

For the most part, I make mistakes in forming the proper noun cases in rapid conversation. Often in Irish, nouns are modified when preceded by compound prepositions, some simple prepositions, and another noun. These modifications are sometimes as simple as adding an extra letter to the front of the word and other times as complicated as altering the word entirely. Composing these on paper has become easy, but applying them in daily conversation is the worst – most younger native speakers don’t bother to use these noun cases. I know this because I’ve been trying to speak with locals of all ages to get a better feel of how different demographics use Irish. In general, the oldest generation, including people born in the 1920’s-1940’s, has the best Irish because they didn’t really have English in their lives until they were grown.

Irish speakers are a minority in Ireland. That ironic statement is based on a generous estimate that out of some four million people on this island, perhaps 30,000 people use Irish as their daily means of communication. An Rialtas (the Irish government) publishes much more gracious numbers based on how many students coming out of the secondary schools can compose Irish, but many people never gain any ability to speak the language in conversation. Reading and writing the language are stressed, not speaking it; sounds a lot like Latin, non?

My host couple, Máire and Steve (very Irish name), have been speaking Irish in the home since they were born, but they’ve also had the influence of English from the mass media and the school system. Considering that Ráidio na Gaeltachta and TG4 were established to promote Irish in radio and television, respectively, and all students have to perform to a certain standard in Irish to graduate secondary school. Nevertheless, Irish and the Irish-speaking community are essentially relics, and shrinking relics at that. At the establishment of the Irish Republic in 1922, there were around a half-million speakers of the language, and that number is now reduced by roughly 90%. According to Máire, Steve, Máire’s mother, and others here in the Gaeltacht, the language and its speakers are “revered” by the Irish, but there’s little substantial effort to make the language a living, breathing part of the national fabric. Rather, it has become an adornment; ageing, honored, and soon entombed.

Just in case anyone’s actually reading this thing, I want you to know that I’ve hitch-hiked back to the house three times so far, mostly with locals who knew where to drop me just from the name of my beann an tí (lady of the house). That’s what I call community.

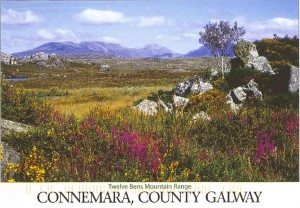

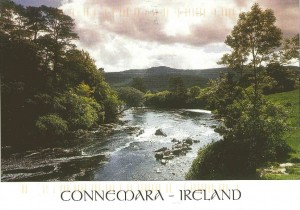

Postcard(s) from Abroad:

Reflection on my language learning and intercultural gains:

I did not gain the level of fluency I wanted to reach during the month I spent in An Cheathru Rua. Even though I spent all day hearing and speaking the Irish in the home and at school, I was impaired by the considerable prevalence of English in the community there and amongst the other students. The most important lesson I took away from this trip about language acquisition is the same lesson I’ve been gradually learning my whole life: listen twice as much as you speak. It wasn’t enough to try and stumble through a conversation with native speakers; I had to articulate very brief, concise statements after I digested what I just listened to (with). I’m certainly no Yeats or Synge yet, but with more practice hear at school, I can continue to build on what I learned in Galway.

Reflection on my summer language abroad experience overall:

Although I did not gain the level of fluency I desired in four weeks, I made huge leaps towards capturing the spirit of the culture that the Irish language represents. First, I was a bit over-ambitious to think I could make too much ipmrovement in just one month, but ambition isn’t the worst fault I could have. Second, I see language as one tool to understand people and their culture, and even if I cannot yet speak Irish fluently, I listen and understand. After just one month, I know what the West of Ireland is all about – tradition, family ties, stubborn independence, and except for matters of the weather, a happy life.

How I plan to use my language and intercultural competences in the future:

I have believed from the start, and still believe, that the best way I can use my brief experience in the Gaeltacht is to teach the Irish language. Does that mean I need to become a professor of letters in Irish? I think not. Right now, I’m working as an Irish tutor, and when I leave Notre Dame, I plan to stay active in Celtic associations wherever my military career takes me. As a language that is swiftly falling out of regular use in its own country, Irish needs to be studied and spoken by its aspiring students with great diligence and passion, and though I’m not the most skilled Irish speaker, my love for the language takes me a long way.