Name: Emily Ransom

E-mail: eransom@nd.edu

Location of Study: Rome, Italy

Program of Study: Living Latin in Rome: The Paideia Institute

Sponsors: J. Patrick Rogers & Stacey Yusko

A brief personal bio:

Emily Ransom studies literary and religious culture in sixteenth-century England and Ireland. She hails from the UNC Chapel Hill (B.A. 2005) and North Carolina State University (M.A. 2009), and has also studied Greek and Latin at University College Cork and Irish at the National University of Ireland Galway. Her particular research interests include early humanism, Thomas More, the English reformation, biblical poetics, and the revival and suppression of languages such as Anglo-Saxon, Irish, and Greek during the English renaissance. She has published in Moreana and Studies in Philology, and has delivered papers at the Renaissance Society of America and Kalamazoo.

Why this summer language abroad opportunity is important to me:

The Paideia Institute provides students with a unique opportunity to study Latin as a living language, the way that the authors I study would have known it. So far, my work as a scholar of Renaissance English literature has focused on Thomas More, who wrote most of his early works in Latin. While I have been able to utilize Latin texts of More‰Ûªs epigrams, /Historia Richardi Tertii/, and translations of Lucian, my research is getting to the point where merely following the sense of a passage is not enough. I will need to hear the nuances of syntax and expression in a way that is only possible with a living language. This opportunity has direct implications for my aspirations as an English scholar. While many contemporary Renaissance researchers read Latin works in translation and occasionally struggle through the Latin of specific passages, the original texts are becoming increasingly inaccessible for modern literary scholars. Not only are we unable to read neo-Latin texts with the ease and comprehension of their original readers, but many sixteenth-century texts have never been translated. My long-term goals as a scholar involve making Latin texts accessible that would otherwise remain buried in obscurity.

What I hope to achieve as a result of this summer study abroad experience:

The opportunity to learn Latin as a living, spoken language and to experience Rome in its ancient tongue would be unlike any other. In a time when most English critics approach Latin slowly and limpingly (if at all), this course would teach me to read it comfortably as one could with a modern language by teaching it the way one learns a modern language: by conversation. There are many questions I have as a scholar of Thomas More that cannot be answered by a stranger to the language (What is the rhetorical significance of the apparent stylistic shifts in his /Tyrannicida/? Do his metrical oddities in the /Epigrammata/ have auditory explanations?). Furthermore, as I think about my career as a scholar, this course would open doors to work with writings that are becoming increasingly neglected, and I hope to leave behind accessible editions of works no one has handled in centuries. I hope to become a translator not only of the words of Latin, but the sense, nuance, beauty, and character; and I can only do that if I first learn to hear the life still in it.

My specific learning goals for language and intercultural learning this summer:

- At the age of the summer, I will be able to speak and compose in Latin as much as I can in French.

- At the end of the summer, I will have composed and delivered at least one oration and one poem in iambic hexameter.

- At the end of the summer, I will be able to read unseen Latin texts without stumbling on the pronunciation.

- At the end of the summer, I will recognize nuances of mood and syntax in classical Latin.

- At the end of the summer, I will have an increased vocabulary enough to read most Church Latin without a dictionary and to get the sense of Ciceronian Latin.

My plan for maximizing my international language learning experience:

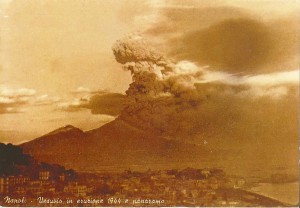

The daily classroom setting involves the study of language literature every morning and visits to cultural sites every afternoon, actively using Latin to interact with instructors and peers in both cases. Class activities include debating in the Coliseum and touring Vatican excavations, experiencing Rome in the language of the ancients. While it is not possible to stay in the home of a native speaker, students will live in apartments where we can use the Latin with each other at night as well. In addition to the grammar, literature, and daily explorations of Rome, we will take weekend trips to the surrounding areas and visit significant historical sites such as the Grotto of Tiberius, Hadrian‰Ûªs Villa, Sibyl‰Ûªs Cave, Mount Vesuvius, and Campi Flegrei. From what I have been told about the course, I will be breathing Latin with an intense concentration. Nevertheless, in the event that any evenings might be free, I have been in contact with the Missionaries of Charity in Rome. While I am prepared to devote as much time to Latin as the course demands, I hope to have opportunities to serve the city while I am there as well.

Reflective Journal Entry 1:

Today was the first day I have ever attempted to use Latin in conversation, and the task was every bit as daunting as I imagined it. Various grammatical nuances that I had only studied beforehand in the context of systematic charts for memorization suddenly became every bit as essential as they were inaccessible in the moment, and I realized what a valuable recourse this course is going to be for me. In order to make the course as useful as it can be for me, I am deciding on a number of disciplines I am going to try to maintain throughout the duration of the course.

First of all, I am going to commit to composing in Latin daily outside the context of class and homework. Preferably, to record my time in the eternal city, these will be musings as I travel around different cites in the city. This will force me to expand my range of available phrases beyond what is available to me on the spot in class, and hopefully this will allow me to become more familiar with the necessary vocabulary I need. It will also facilitate memory when I hear teachers or classmates say phrases correctly that I have struggled to compose incorrectly.

Secondly, since I know my ability to read aloud is weak, I’m going to practice reading texts aloud daily outside of class. Since I am in Rome living a couple blocks from the Vatican, it seems appropriate to read the Liturgy of the Hours in Latin, and to make use of the various churches around the city to do so. If I am faithful to say at least three of them a day, this should help my ability to pronounce Latin tremendously.

Reflective Journal Entry 2:

In my first week of Living Latin classes, I had two amazing opportunities that connected me to Latin as a spoken language in a way I could not have had anywhere else in the world.

After reading several first-century accounts of Roman gladiatorial battles in class, we were taken to the Coliseum and separated into groups in which we prepared arguments for and against the value of gladiatorial games for the Roman Republic (in Latin, of course!). Afterwards we reconvened and selected representatives from each group to deliver orations in pairs to argue our assigned case. As it turned out, no one in my group was willing to stand up before the class, so while all the other groups sent pairs, my group sent only me. There I stood in the Coliseum itself where centuries of Romans watched people killed for entertainment, and I was forced to argue for the value of gladiatorial games in Latin before a group of people who spoke much more Latin than I do. Though my actual performance left much to be desired, the last-minute, make-shift nature of my oration forced me to overcome inhibitions and encouraged me on the journey towards spoken Latin.

Three days later, I was selected as one of six students in the program to perform a scene from Plautus in a first-century theater in Ostia, almost adjacent to the place where St. Monica died. It was an invigorating experience to stand in an ancient theater in Ostia with Latin-speakers around me, bringing the words of Plautus to life again with all the gusto I could muster. I was thankful for the experience of daily Latin readings outside of class that I have been forcing upon myself, because even a week ago I would have stumbled over the words much more than I did.

While the program has forced much spoken-Latin experience on us, and while my side-efforts to journal in Latin and read through daily prayers in Latin have been helpful, I have felt the need for more experience speaking the language. Thus I am organizing regular Latin lunches outside of class. There is quite a bit of enthusiasm for these lunches form my other peers, and we plan on gathering after class three times a week for lunches in which English is forbidden. This will force us to learn not only to speak in Latin in the formal class-settings, but also to speak it in our casual times normally given over to relaxation. I am hopeful that regular Latin lunches will help me to make the language not only alive in places like the Coliseum and the theater of Ostia, but also in my day-to-day life.

Reflective Journal Entry 3:

This week I began arranging optional Latin lunches after class on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays. At this early stage of the program they have been quite popular with the students, especially those of lower levels. As long as we arrange the seating such that the higher-level students are accessible to most students, the conversations seem to be going smoothly. I managed to share the story of a run-in I had with a sketchy Italian stranger in Latin at our first lunch. I found that simple words I struggled to remember at the beginning of my story (words like “rogo,” to ask) became second-nature by the end of the story and subsequently for the rest of the week.

In addition to the lunches, the program has increased its demands of our spoken Latin experience. For example, when we visited a church on Monday, we were commanded not to speak any English after we entered the doors, and given an assignment to discuss the meaning of different memorials on the walls inside. My group consisted of a student who was already conversational in Latin and one who was just beginning, and I served as somewhat of a bridge between them. It was tremendously challenging to attempt to explain and define Latin words in Latin, but by the end of it we had deciphered our memorial and could explain our discoveries to the rest of the group.

I am appreciating the practice of translating English poems into Latin in my spare time because it takes away the pressure of trying to think of what to say and allows me to concentrate on how to say it. This avoids the problem I ran into on Wednesday, when I was supposed to debate about the identity of a figure in a monument (either Aeneis or Numa) with a group of classicists though I was too unfamiliar with the characters to share any insights (even if the debate were in English), or on Thursday, when I was asked to describe the beginning of the Trojan War and the instructor thought my answer did not go back far enough. I need spaces where I can practice the Latin itself without worrying that I don’t have enough of a classical background to come up with the right answers.

On Friday we visited the church of Saint Clement, a Renaissance church built over a medieval church built over a first-century street. In the medieval level of the church, we sang Gregorian chants in Latin. The next day we visited Saint Benedict’s abbey in Monte Cassino and Saint Thomas Aquinas’ hometown, finishing our trip at the monastery in which Aquinas died. There we sang some of his Latin hymns and read the Latin account of his death in the room in which he died. The instructors asked for four “brave” volunteers to handle the convoluted Latin, and after three of the advanced students went up I volunteered to be the fourth. The effort to translate a long passage of unseen, medieval Latin in front of all my peers was intimidating, but the experience of reading a first-hand account of Aquinas’ death in the room in which he died was well-worth the struggle.

Reflective Journal Entry 4:

I was asked to write an account of my journey to Rome. This is what I came up with:

Abscondens sinum meridianum, vehiculum meum conscendi cum meo cane fidele. Mente fixo Carolinam Septentrionalem autoraeda celeritudine ultimo festinavi. Me adveniente familia laudavit, etsi nimis paulisper. Cum cupidinem ut ad Romam iter faciam ostendi, defluxerunt et me precati sunt ut restitem, sed sicut lapido certa fui. Propensis ventis iter velox et brevis, atque contacto littoro Tiberis frater Nestor Augustinius me amplexans profusum prandium mihi arcessivit ut secundum multas vias refovebar. Ventis tamen inversibus ante obitum solis, navigium ad Amstelodamum deinde ad Hiberniam difflatum est. Ibi octo dies palata sum, mortem aviae et sponsalium sororis inaudiens. Denique prima luce die decima, nauclerus me navigium destinatum ad Romam conscendere sivit.

Reflective Journal Entry 5:

In the course of Latin lunches, I am becoming much more comfortable using the language. I find that it is easier for me to engage in a conversation if I am interested in the discussion (this explains some of my difficultly keeping on task in class if the discussion tapers off into something mundane). I ended up in a gripping theological conversation the other day about iconography and sacred art in the eastern and western churches (all in Latin), and I found that it was actually an easy conversation for me because I was interested in the topic (not to mention that English borrows most of its vocabulary for religious and abstract words from Latin, so the vocabulary was easier). I may still have a hard time discussing the events of my day, but I can discuss iconography!

Postcard(s) from Abroad:

Reflection on my language learning and intercultural gains:

One of the greatest challenges was learning to think not only in the words of a different language but in their sentence structures, learning to say the kinds of things a Latin author would say rather than simply trying to reframe my English sentences with Latin words. I learned quickly that flashcards were much less helpful for learning to speak than they had been for learning to translate; I made more progress when I practiced vocabulary by using it. In some ways I met my goals: I delivered orations, recited poems, wrote quite a bit of prose. But the process of fulfilling those goals showed me how far I was from doing them well, and thus the summer was a challenge to plunge deeper when I returned.

Reflection on my summer language abroad experience overall:

The experience of interacting with Latin like a living, breathing language transformed the way I understand the authors I study. Part of my lessons were about my own lack of knowledge in the language; the difference between being an adequate translator and competent speaker is vast, and I didn’t realize how far I was from the latter until I was in a situation where I needed it. But I also learned the joy of progressing toward that point: the confidence of hearing Cicero’s words come out of my mouth while standing at his place in the Forum and actually understanding them, the thrill of having a conversation over lunch about iconography in Latin and actually understanding it, the satisfaction of following every bit of a sermon in Latin. The horizon of my use of Latin has been expanded, so while I am more aware of my limitations I have a greater vision for growth.

How I plan to use my language and intercultural competences in the future:

I hope to make journaling in Latin a regular part of my weekly rhythm. Additionally, I hope to find a group of students who would be interested in forming a Latin conversation group, perhaps weekly Latin lunches. But beyond that, I want to continue to interact with Latin authors as if they are living. I am hoping to translate an adage of Erasmus every day, memorizing it and pondering it through the day so I can start to internalize not only my fumbling attempts at Latin prose but also that of the great authors whom I study.