Name: Il-jee Kam

E-mail: ikam@nd.edu

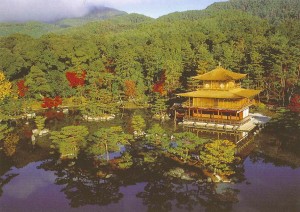

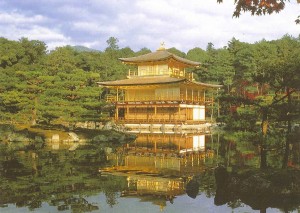

Location of Study: Kyoto, Japan

Program of Study: Kyoto Summer Program in Advanced and Classical Japanese (KCJS) administered by Columbia University

Sponsors: Justin Liu & Bob Berner

A brief personal bio:

I spent most of my childhood in Tokyo, Japan due to my father’s work. Having grown up with friends who were mostly half-Japanese, I frequently considered myself as one and called Tokyo my home. Although I studied at an International and American School in Japan for the 7 years I lived in Tokyo, I was required to study Japanese in class since the first day of school till the last. As I moved backed to Seoul, Korea for high school, I wasn’t able to continue any of my Japanese studies since my high school did not offer the subject. Now, I am almost already into my third year at Notre Dame and deeply embedded to the Japanese learning community on campus!

Why this summer language abroad opportunity is important to me:

Summer language study will be an opportunity to engage into a culture with a new perspective– a more mature and intellectual one opposed to naive and elementary one I had during the years I lived in Japan as a child. I want to take this opportunity to go back to the country I once called home and reflect on how I have developed in terms of my cultural identity, ability to culturalize, and engage in foreign environment. Just the thought of being able to call Japan home again, is compelling and engaging to my personal character development. Working at the CSLC also made me realize the importance of global awareness, of study abroad, and of living the experiences. Having heard and shown of various experiences of my peers vicariously, I also intend on bringing back the essence of the experience that lasts. Making use of my photography and video editing interest, I hope to capture the essence of Kyoto, the cultural capital, through the lens and then share with others and create a product that will endure. I want to partake in dedications the Notre Dame community commits to promoting culture and language acquisition.

What I hope to achieve as a result of this summer study abroad experience:

In my experience, getting most out of a study abroad experience not only includes participation in activities provided by the institution but also self-directed participation in community. Therefore, I hope to partake in independent proactive exploration, which will enrich and maximize personal experience beyond classroom. My goals are to challenge myself to take measure to engage and learn beyond what is provided, to go against the conformity of my peers, and to get out of my comfort zone, in order to fully immerse myself into the community. From this study abroad experience, I intend to engage in a traditional, yet modern culture with a more mature and intellectual perspective for my personal aspiration of character and intellectual development.

My specific learning goals for language and intercultural learning this summer:

- At the end of summer, I will be able to talk about what I study at the University of Notre Dame and why the subject I study interest me.

- At the end of the summer, I will be able to communicate in Japanese with native speakers on academic, political, world event, and newsworthy topics.

- At the end of the summer, I will be able to describe city of Kyoto, how the city maintains its cultural beauty and show a slideshow/video through the internet the magnificence of study abroad experience.

- At the end of summer, I will be able to talk fluently using keigo and polite form.

- At the end of summer, I will be able to better understand my personal character as an international student and will be able to demonstration of significant tolerance for ambiguity and a willingness to take intercultural risks by engaging in cultural and linguistic interactions that are beyond my level of mastery and comfort zone.

My plan for maximizing my international language learning experience:

To “hit the ground running” and take full advantage of my international language study, I found events that occur during the months of study hosted by local Japanese agencies, shrines, culture villages, and organizations that I can participate in. To explore Kyoto, the center of Japanese politics and culture, I selected some of the events that I believe well capture its magnificence. Miyami Nature Culture Village Photography gathering, for instance, is an event for beginning photographers who wishes to learn more about photography through snapshotting moments of “firefly fantasy†in mid-summer. Offered by the same village is Medicinal Herb class, in which one discusses, picks, and cooks these medical plants. Miyazu Cycling tour is devoted to experiencing beautiful natural scenery of the city. Others events include: visiting the special opening of Seiryou Shrine, hiking the historical shrine paths, cockle cooking, field trip to tea factory, and plentiful more.

Reflective Journal Entry 1: Pre-departure

Japan used to be my home until 7 years ago, when I moved out from Tokyo. It was unbelievable that night in Wisconsin at my friend’s apartment, when I received that email from the CSLC for a grant to go to Japan and stay for 6 weeks to study the language and culture that I have missed for 7 years. I am mostly excited about going back and actually enjoying and observing the country I once used to call home and relook at the kind of place I grew up in. I’m still quite not sure of what to expect for the program, but I am just thrilled by the fact that students, who have similar interest as I but for unique purposes, from all over the nation are going to gather in a beautiful city to study the language and culture. Although I did have classmates in my fourth year Japanese class at Notre Dame, for some reason, I expect this program to have students who are really passionate about learning Japanese and its culture. With all those concerns behind, I am physically and mentally ready and excited to leave for a new home for the next 6 weeks!

Reflective Journal Entry 2: Culture, Tradition, Modern in One

During the first couple weeks of the program, I became very close to another Korean student who had come to study. One day we decided to go out Biwako, the biggest freshwater lake in Japan for a bike trip. On our way, as we were cycling along the lake and watching the scenery, we got into the discussion of how Kyoto remains as the cultural capital city of Japan. As Korean international students, we both believed that Seoul had lost its Korean uniqueness and believed it to be the reason why many Japanese tourists believe Seoul to be no different than Tokyo. My friend who had just got accepted to a one of the most prestigious graduate school in Korea to study Korean and Japanese architectural difference and I enjoyed the long discussion of comparing Seoul and Kyoto during the trip.

The trip and conversations we had inspired me to simply observe buildings and towers all over Kyoto for the remaining days. The more I saw, observed, and learned the city, the more I had wished Seoul to have developed in ways Kyoto had. Japanese culture for one, was easily embedded in Kyoto due to the numerous national and cultural heritage, which are protected by the law. However, beyond the buildings, primarily the temples, that are protected- over the six weeks of stay, I was fascinated by how even the downtown streets of Kyoto consisted of Japanese traditional music, architecture, and fashion. I found it amusing, walking down the mainstream shopping center called “Teramachi” (literally translated Temple Town) that had once been a temple town and its remains kept in the corners of the shopping street. Although buddhism seems spiritually embedded into the culture, it was a realization that this embedded culture appears in physical form as well.

Reflective Journal Entry 3: Zen

Today (July, 6, 2012) a monk from a temple nearby visited us to give us a lecture on Zen. Unlike what most imagine a monk to be, he was young –perhaps in the llate 20s or early 30s– big and fit, dressed in casual black polo t-shirt, and had international education. He began defining Zen by introducing the different views of zen, which differs across cultures. According to this monk, zen is to focus on one subject, while sitting, for satori, an awakening and enlightenment. According to him, zen is not only a religious tradition but have become a culturally embedded tradition that predominates in everyday life such as: small, yet simple tea house designs, Japanese Toyota car designs that are simple and easier to customize, and most importantly bathrooms. According to a research, best schools and business buildings are those with good bathrooms, in which zen can be practiced. Japan’s attachment to invent of bidets apparently is rooted in the quality time that can be spent alone in the bathroom stalls. The high quality of bathroom environment is not only due to sanitary reasons, but for the high quality of alone time, which reduces the stress levels and thereby increases the work and study behaviors. His explanation someone answered my curiosity towards the unreasonable expenditure on high-tech bidet toilets of companies and households. Zen and many other buddhism quality is naturally embedded in the Japanese culture. In Kyoto alone, there are 2,000 temples, 70,000 in all over Japan– number that exceeds the number of convenience stores in Japan. Due to the merge of the religion and everyday life, he claims that many are non-religious yet superstitious. He estimates that 9 in 10 are atheist or agnostic, yet all 10 would hold a charm (omamori) to prevent anything further agonies and for their afterlives (if there is any). As an agnostic myself, it was a food for thought to my spiritual identity and the position I stand among my peers.

Reflective Journal Entry 4:

TASK 1: Identify 2-3 colloquial/slang words in your target language. Next find 1) a man and a woman who are 18-25 years old and 2) a man and a woman who are 40-50 years old. Ask each age and gender group what they think about these slang terms. Do they understand them? Are they appropriate to use? In what contexts? Why? Note the differences and the potential cultural implications for their responses.

I found a selection of Japanese slangs on a website and selected ones that I did not know myself from the top 10 popular slangs of the week. My classmates, consisted of 2 females and 3 males from all over the United States, who studies Japanese language, culture and literature had absolutely no clue on all four slangs.

My host father, one of the oldest participants in the activity, must have known what it was since it the term has been used since the 80s. However, how he defined the term was usable only in negative context, whereas today, the term can be used in positive context as well. Such as it is so “bad” that it is good. As for the rest of the terms, he either had no clue or only knew of its literal meaning.

My Japanese teacher who is in his 40s, but looks like in his early 30s, was able to guess what “to-ri-ma” was. It only took him about 30 seconds to figure out what it was abbreviated for. Although he had known “a-ra-fo”, he was unable to figure out the slang definition of “tep-pan” just like my host father. It was quite entertaining when he pointed at himself and said he was “a-ra-fo” himself.

My conversation partner who was 22 knew all the definitions and the correct usage of the slangs. I showed her the website of slangs and as we were looking through it together, she was learning most of them with me. However, the ones that I had picked from the top 10 list seemed to be used frequently among her friends, especially “to-ri-ma” when she and her friends text. She also told me that her mother who was in her 40s also use “a-ra-fo” and laughed at how silly she thought it was.

From the trends that I have seen while doing this task was that slangs are definitely embedded in the modern culture and therefore is difficult for students who study Japanese culture in class, like myself, and for older people who live isolated from the youngsters. My Japanese teacher, I believe, was able to guess what a slang had meant since he lives a young lifestyle and spends most of his time on a college campus. On the other hand, my host family hosts many foreign college exchange students who come from all over the world to study Japanese. therefore, he is more exposed to young numerous cultures than to actual young Japanese culture.

Description of term

よう (Yo)

クラスのみんな (Class) お父さん (Host Father) 先生 (Japanese Teacher)

1. えぐい (e-gui) Used since 1980s, originated from a commercial えげつないー しらない。。 えげつないーそれは昔から使われているね えげつない

2. とりま(to-ri-ma) Used since 2006, internet slang, short for とりあえずまって(to-ri-a-e-zu-mat-te) = just a moment とりあえずー待って メールとかでよくつかっている 聞いた事ない。。。 しらないねえ〜 うん。。。何かの略やな。。とりあえず。。待ってとか?

3. 鉄板(tep-pan) Used since 2006, term itself literally means metal plate used to cook

定番?あたりまえじゃん? like hot pan? お好み焼きですか? ??

4. アラフォー(a-ra-fo) Used since 2008, short for around fourty (years old), originated from title of drama 40歳ぐらい?ようの母も使っているらしい 聞いた事ある! わからないな〜 俺の事や〜

Reflective Journal Entry 5:

TASK 2: Identify a current and controversial social topic in the newspaper; select something that is perceived as more of cultural issue than a purely political one. Next, find three native speakers to interview on this topic. Briefly ask them for their opinions on the topic and explore their rationales. Do not inject your own opinion into the interview and remain objective and respectful even if you do not agree with their statements. Consider how cultural assumptions influenced your perception of events/issues and the responses of your interviewees.

For this task, I was able to interview my conversation partner and two of my friends that I have met at a language table for both Japanese and International students at Doshisha University. I decided to interview on the topic of why Japanese students don’t study abroad and discussed our opinions on the topic. I must say that the interviewees were unconventional ones of the bunch on campus. Unlike what most Japanese students, these three showed interest towards the international students and international culture the campus had to offer and made their approaches to the international community on campus.

If I had to describe Yo in a single word, I would (without a doubt) select “ambitious.” From the first day we had our conversation session, she told me about: how she had once applied to, got accepted to and studied abroad at University of Oregon as an exchange student for a year, her travels in the United States, and most importantly about her future goals of taking all these experiences to another level- working for a Middle Eastern trading company. After several weeks, when we became closer friends, I explained to her of my task and asked for her opinion on why Japanese students don’t study abroad. Shintaro and Yasu were friends, who organized the international conversation table that I attended. Shintaro has never been abroad but had significant interest in America. Yasu on the other hand has been to Boston for the career forum last fall and was looking into visiting again for this fall. The two had very different personalities and at times had clashes while preparing for the conversation group but were able to get along for the sole purpose of gathering group of Japanese students and international students to be “friends,” unlike ones official organizations that tried to “use” the international students as “resources.”

After hours of talking, the cultural issue of Japanese students not studying abroad builds upon many student’s “timidity.” All of three of my interviewees reported that many Japanese students have fear speaking foreign language, are too timid to be exposed to other cultures and most unfortunate of all don’t feel the necessity of getting to know other cultures. They also believed that many students on campus are not taking the opportunities to the talk to international students. Shintaro says that one of his biggest lesson learned becoming friends and talking with international students from multiple backgrounds was –borrowing his words– “wherever we may come from, we aren’t too different.” He found out through actual human to human interaction that the most important part was communication– the exchange of down-to-earth affections, behaviors and cognitions. He added that many Japanese students –even his friends– lack the experience to realize this fact and only fear the interaction with those of blue eyes or dark skins.

My cultural assumption regarding this issue comes from my study on typical characteristics of islands. For a geography class, I was taught that generally, since an island is surrounded by the waters and those who are on the land have nowhere to “runaway,” islanders have the tendency to be conformist who don’t go against each other to create peace within. In some aspects, I still do believe that my assumption has been enhanced by some of the reasonings my interviewees enilsted behind why Japanese student’s don’t study abroad; many feel that multicultural experience is troublesome and therefore create a barrier for themselves against other cultures.

TASK 4: Identify two people who are members of a social/ethnic/racial/economic minority in your country of study. Ask them about their minority status and how they feel that they are treated by majority members of the community. Note cultural attitudes that influence the treatment of minority communities in your country of study and how these attitudes differ from the US.

For this task, I was able to talk to two of my closest friends during the program. One calls herself as the “I have everything easy,” white and blue-eyed girl, who has visited Japan multiple times and lived in Japan for two years during her years at the JET Program. Another girls herself half german and half black girl with “spring-like” hair that goes “uncontrollable-crazy” in humid weather, who spent her first six weeks abroad, during the KCJS program.

According to my first friend, her experience as gaijin (foreigner) is most difficult when she wants to be “normal.” Anytime in convenience store or trying to make a decision at a store, people automatically treats her as someone lost and who is in need of help. At times when she wants to enjoy her moments at temples, zen gardens, or even at bus stops,, there are kids looking at her and saying “haroo” (hello in Japanese-English pronunciation) and ruining her moments. According to her experience, the most disappointing about being a white gaijin is the interaction that occurs with other white gaijins who ignore her or even avoid eye contact because they believe it ruins their “Asian” moments. My other interviewee on the other hand rather had difficulty as becoming a part of the community due to the stares and avoidance. Just like my first interviewee, she received stares but no hellos, so the only thing she could do was to give them a smile. On buses, she claims that she felt that people would rather stand than to sit with her.

Physical features play a great role in how one treats another and evidently, race plays a great role in our appearance and how we treat and are treated. Stereotyping and prejudice of race, in my experience, is a significant factor especially in a non-diverse countries like Japan (and Korea). The lack of exposure to those of other skin and eye color, I believe is the the founded problem in how we view and treat others. Despite how much of a tourist city, Kyoto has become, I realized from the different treatments of the two interviewees that Japan, yet has a diversity cognizance difficulty to overcome.

Reflective Journal Entry 6:

TASK 5: Identify a food/dish/cuisine that is unique to your location of study. Go to a local restaurant and order the food. Engage the waiter/restaurateur in discussion of its ingredients, preparation and presentation. Ask about the historical or cultural significance of the food. Why is it so popular locally? What distinguishes a good preparation from a bad preparation. Note the culturally-bound attention to food and its role in nutrition, social interaction and/or national identity.

Osaka, another city 30 minutes away from Kyoto, is known for Okonomi-yaki and Tako-yaki. Okonomiyaki literally means “what you like-cooked” and Takoyaki, “octopus-cooked.” Like its name, Okonomiyaki ingredients vary as however one prefers. They are a type of pancakes with usually seafood or meat, cabbage, topped with katsuo-bushi (dried, fermented, and smoked skipjack tuna), aonori (green laver), mayonnaise and special sauce. On the other hand, takoyakis are ball-shaped Japanese snack made with flour based batter with piece of diced octopus, also topped with katsuo-bushi (dried, fermented, and smoked skipjack tuna), aonori (green laver), mayonnaise and special sauce.

Okonomiyaki originated over 400 years ago and is rooted in “funoyaki.” which were crepe thin flour pancakes with miso sauce. As for Takoyakis, they orinated in 1933 and is rooted in “Radio-yaki,” similar to Takoyaki, without octopus. There are over 650 Takoyaki stores alone in Osaka and yet remains to be the two of the most famous foods in the area. The greatest part of Okonomiyaki and Takoyaki lies in the cooking process, in which one can enjoy making Okonomiyaki at the table on your own teppan (metal griddle) and watch Takoyaki chefs make Takoyakis on special pan. Takoyakis are also easily made at home with pans available at every electronics store. Although they aren’t the most nutritious cuisine, they are quite popular among family and friends due to the inevitable social interaction that brings people together. Getting together to prepare a good plate of okonomiyaki and takoyaki doesn’t require much ingredients and effort, but the time it takes to make one plate can take about 15 to 20 minutes at the table, requiring people to interact. Good prepared Okonomiyakis are usually about two centimeters thick, decorated with katsuo-bushi, aonori, mayo and special brown sauce. Good prepare Takoyakis are crispy on the outside, soft on the inside, and topped with the same toppings as Okonomiyakis. Best okonomiyakis and takoyakis are topped with “dancing” katsuobushis.

Reflective Journal Entry 7: Post-departure

My place of stay for the six weeks was not a homestay or an apartment but a guest house owned by a couple of my grandparents age. The housing for this “Kajiwara House” did not mandate Okaasan (Literally, “mom”) to cook for us but she always treated us with fruits, snacks, breakfast and such. Otoosan (“dad”) always told us about Kyoto, primarily how fascinating the city is. Although the intensive six week program and touring had kept me busy during my stay and so little time was spent with my host parents, the good-bye with them were the hardest ones I had ever had to do. As my taxi driver was loading my luggage into the van, Okaasan and Otoosan kept reminding me that I’ve been the greatest guest they have had and that I was more than welcome to come back any time. At that moment I was very happy to have left them a card saying they were my parents of Japan. As I got on the taxi and waved them good-bye, I had realized that I had not only fallen love with the city but with warmth of people that makes the city such a wonderful place to live in.

Postcard(s) from Abroad:

Reflection on my language learning and intercultural gains:

Having grown up in Japan, overcoming and understanding cultural differences was not very difficult. Since I assimilate to the Japanese locals, most treated me as if I was a part of the country. For instance, in a restaurants when I visited with couple of my gaijin (foreigner in a Japanese perspective) friends, the owner assumed that I came with them to introduce Japanese Ramen. My physical appearance played a great role in acculturation. In terms of language acquisition process, I learned more ways to learn the language. As a goal, I wanted to make effort to enhance my insights into advancing my Japanese with the resources that were not easily accessible back at Notre Dame. Therefore, I made frequent visits to a second hand bookstores, bought books that are relevant to my major and interest, tried to understand and be able to write about them, watched news on television every night, practiced listening advanced level Japanese with the help of subtitles, joined a Japanese student community who were interested in gathering both international and local Japanese students to have conversation tables. Doing all these things definitely allowed me to meet my goals, but at the same time made me realize how much more studying I had to do.

Reflection on my summer language abroad experience overall:

To those who are preparing for their own summer language study, I suggest them to prepare enough to keep them started for the first week or so and to do the rest of planning later at the place of study. Overall, the summer language abroad experience taught me to keep myself open to the community and what has to come. During the short six week, the unexpected and spontaneous experiences are ones I enjoyed the most and remember the most. The unexpected, especially comes along with the learning community. I got to work with classmates, friends, and instructors, came from distinct backgrounds; I can without a doubt claim that they enriched my learning experiences the most during my stay. Having discussions with graduate students who studied various aspects of Asian culture– taiko (Japanese drums) in matsuri (festival), Japanese education system, Japanese eating habits, etc– who are more aware of some cultural aspects of Japan than I am stimulated me to various areas beyond the language itself, living with my host family taught me what it means to be a part of a Japanese neighborhood, studying with a classmate who has never taken a single Japanese course but had self-studied her way to this class made me respect those who sought international endeavors. Again, my only advice in preparing for a study abroad experience is to let the unexpected happen.

How I plan to use my language and intercultural competences in the future:

Having spent six weeks with students from various backgrounds, studying the subject of interest mostly allowed all of us to engage into the language and culture more in depth. Most importantly, spending time with students who were more aware, more sensitive to cultural matters in Kyoto enlightened me to think about what I see, hear and hope to pursue in a new perspective that I would have never gained at Notre Dame or back home. The language acquisition gain that I have made during the six weeks of stay without practice will gradually diminish, yet the intercultural gains that I have attained and insights into the language acquisition process, outlooks into tourism culture, experience of living in a interdependent culture without the guidance of family members but with strangers from different backgrounds, simply way of perceiving will persist through out my career and post-graduation. The SLA Grant experience, most importantly, was a catalyst for my personal growth in understanding myself in diverse situations.

* For the first task, there is a table that I have made, but it won’t let me copy paste into table format! 🙁

Pingback: Homepage

Pingback: เก้าเก เล่นยังไง พร้อมกติกาอย่างละเอียด

Pingback: siam855 ทางเข้า หวยออนไลน์

Pingback: แนะนำ 5 วิธีเล่นบอลสเต็ป

Pingback: Download Songs Online

Pingback: สายมัลติคอร์

Pingback: รับนำเข้าสินค้าจากจีน

Pingback: คลินิกเสริมความงาม

Pingback: กติกาบอลสเต็ป

Pingback: รับเขียนแบบบ้าน

Pingback: ของพรีเมี่ยม

Pingback: Go to instructions

Pingback: visit

Pingback: monumenmasters

Pingback: kc9

Pingback: Aviator game online

Pingback: fox888

Pingback: สับปะรด สล็อต ฝากถอนออโต้ ทรูวอเลท

Pingback: Freshbet

Pingback: Lisa

Pingback: สล็อตเว็บตรง th168

Pingback: pg168

Pingback: เว็บปั้มไลค์

Pingback: เล่นเกมยิงปลา กับ ค่าย jili

Pingback: ร้านดอกไม้

Pingback: รวม เว็บ G2G แทงบอลสด รวมกีฬาออนไลน์

Pingback: parki.lv

Pingback: รับติดตั้งระบบระบายอากาศ

Pingback: โคมไฟ

Pingback: deepseek

Pingback: นัดเด็ก

Pingback: บาคาร่าเกาหลี

Pingback: Lowara

Pingback: ระบบสมาชิก

Pingback: buy instagram views

Pingback: ayurveda retreat

Pingback: Court Documents Research