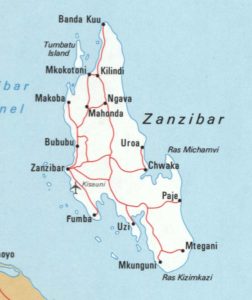

On Saturday August 3rd, Abdalla Daudi, Omar Bakar, and I arrived at the daladala bus station in Stone Town, packed and ready to go for our trip to Tumbatu Island. We had aloe-based soap, toothpaste, toothbrushes, and plenty of sunscreen. These items were among the gifts to be given to the three albino families we were going to meet on Tumbatu Island. We had a two and a half hour bus ride ahead of us, which we survived amidst our occasional doubts, as the packed vehicle frequently navigated tough road conditions. The destination for our bus ride was Mkokotoni in the northern part of Unguja (Zanzibar). Once at Mkokotoni, with Abdalla and Omar by my side, we set off on a 25-30 minute adventurous boat ride to the distantly visible island of Tumbatu.

Map showing Tumbatu (from Map of Zanzibar and Pemba, 2005. Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division).

When our boat arrived it docked 100 yards out from what appeared to be the shore. Seeing that I was surprised to see people walking around the area in which our boat was docked, Omar explained that we were about to be walking on a shallow reef, where many of the locals venture to collect crabs and clams to sell to mainland Zanzibaris.

Arrival at Tumbatu Island. Photo: Nyakeh Tuchscherer

Arrival at Jongowe on Tumbatu Island. Photo: Nyakeh Tuchscherer

Once we reached the sand, Abdalla led Omar and me into the small village known as Jongowe or Tumbatu Jongowe, which is on the southernmost part of island. This is one of the main settlements in Tumbatu, which is by the way a very small island – only about 5 miles long and 1 mile wide – and doesn’t have a single car or road. We followed Abdalla through winding narrow pathways and around a matrix of houses until we finally reached the home of the Hassans. There we met the Hassan family as well as their neighbors, the Juma and Sheha families. Two or three big carpets were assembled on the ground and we all sat together under a shaded tree, protecting us from the overcast but still dangerous rays of the sun.

Meeting the Hassans, Jumas, and Shehas at Jongowe. Photo: Abdalla Daudi/Omar Bakar

Abdalla knew the families very well personally as well as in his capacity of chairman of Jumuiya ya ma Albino Zanzibar (Association of People with Albinism in Zanzibar). Omar and I introduced ourselves to our new friends, with Omar explaining in Kiswahili that we wanted to personally greet them and that we had brought gifts to mark the occasion. With Omar translating for me into Kiswahili, I addressed the three families, thanking them for receiving me in their homes, and asking them to share their stories of the challenges they face from the sun and the hurdles they face socially. First to come forward was ten year-old Ibrahim Sheha, the youngest out of the 11 albinos present. “At school, although I’m the best in my class, I have to work harder and longer because I cannot see the blackboard or read even from arms-length away. I have to put the book directly in my face,” Ibrahim explained. His mother, who does not have albinism, then shared how his condition impacted the family circle as well. “When Ibrahim was born, his father left me and wanted nothing to do with us because our son was an albino. He was ashamed,” she explained.

Photo with the Hassans, Jumas, and Shehas at Jongowe. Photo: Abdalla Daudi/Omar Bakar

Fifty year-old Haji Hassan Juma, the oldest person with albinism in attendance, recounted issues regarding safety and his constant battle with poverty. “Here on Tumbatu we are safe but sometimes we still hear about mainland Tanzanians coming to Zanzibar in search for albinos.” Haji explained that that wasn’t the only obstacle to living comfortably. “Tumbatu only has work for agriculture and we cannot spend long hours in the sun or we will get burned or go blind. We can’t do that work so we try to stay indoors, breed chickens and sell them. It’s still not enough.” He shared that although many villagers were understanding and supportive, there were still some in the community who were uncomfortable with the presence of albinos, “so we tend to walk around and go outside at night.” Haji added, “We don’t know why people hate us. There are some who treat us no different from others but we still know we are different and live very different lives.”

The condition of albinism extends just beyond the realm of science and health. There are many social boundaries, and discrimination and persecution are suffered by those living with albinism. The condition prohibits people like Ibrahim and Haji from living regular lives socially, physically, and financially.

I thought of the first time I had met my friend, Abdalla. We had met just outside SUZA when my Kiswahili class finished and we were walking to a restaurant. At the time, children were just getting out of madrassa school, running loose everywhere on the streets. Every other child passing us by shouted the words “zeru zeru.” Abdalla said nothing, just kept his head down under his cap. I asked Abdalla, using my Kiswahili, what those words meant. “Bad bad word for albino,” he responded in broken English. Omar was with us, and he explained that the phrase is used as a derogatory term for albinos. It translates as something like “ghost” and is hurtful, denying the humanity and dignity of albinos. This is the subtle and normalized form of discrimination faced by albinos daily, which pales in comparison to the dangers they face from those who seek to kill or maim them in pursuit of body parts used in ritual magic.

As we sat and shared stories under the canopy of trees at the Hassan compound, Abdalla explained that albinos in Zanzibar, in Tanzania, and throughout Africa need support. He explained that “Many albinos can’t even read because the fonts in books are too small and they don’t have glasses, people from mainland Tanzania travel to Zanzibar to capture us, and employment is really bad because nobody wants to hire us and we can’t work outside…options are limited.”

The time slowly slipped away until we realized darkness would catch us soon if we didn’t move fast. We said our ‘goodbyes’ and the three of us made our way back to the shore, walking out along the reef once again to catch our boat back to Mkokotoni on Unguja.