Name: William McMahon

E-mail: wmcmahon@nd.edu

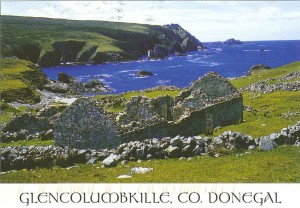

Location of Study: Donegal, Ireland

Program of Study: Oideas Gael

Sponsor(s): J. Patrick Rogers

A brief personal bio:

Having lived in Florida for most of my life, I was unsure about coming to the frozen tundra of northern Indiana. Despite the periodic cold (my major complaint), I greatly enjoy my time here as a History major and an Irish Language & Literature minor.

Why this summer language abroad opportunity is important to me:

My SLA Grant is allowing me to travel to a small Irish village in the Donegal Gaeltact, to better learn the language. This is important to me both as an object of personal fulfillment and as a tool for my future research. Personally, I am enthralled by the way one has to think in the Irish language, and the very different sense of self and the material world it embodies (“A pen is at me” vs “I own a pen” in English, or “A sadness is on me” vs “I am sad” in English). Moreover, knowledge of the Irish language is vital for historical study of the island before the 19th century.

What I hope to achieve as a result of this summer study abroad experience:

I hope to dramatically increase my proficiency in using and comprehending the language at a normal pace, and set myself down the path of fluency. I hope to build a solid foundation for continued intermediate and advanced language classes at Notre Dame, so I can make the most of my opportunities. I also hope to gain a better understanding for the culture and modes of thought that gave birth to such a language, and have personal interaction with native speakers who have lived with the language all their lives.

My specific learning goals for language and intercultural learning this summer:

1. At the end of the summer, I will be able to communicate in Irish with native speakers on a wide range of topics with roughly the same speed as in English.

2. At the end of the summer, I will be able to discuss history and philosophy in Irish in some detail.

3. At the end of the summer, I will be able to think in Irish for days at a time.

My plan for maximizing my international language learning experience:

Outside of direct instruction, I intend to spend all my free time in the local community, interacting with native speakers. I want to have encounters in both commonplace and unusual situations. Shops, community centers, and other public places will provide me with all the experience I need with general interaction, while more prolonged conversation with individuals will hopefully stress my language skills to the point where they are forced to grow. I intend to place myself in situations in which I must learn new aspects of the language to deal with my interactions with the native speakers.

Reflective Journal Entry 1:

14 June 2012 —

I’ve just landed in Baile Átha Cliath (Irish for Dublin), and my program starts in a couple days. I’m seriously jet-lagged, so hopefully that clears up soon. From what I know of my program (Oideas Gael, in Gleann Cholm Cille, Co. Donegal), the focus will be on speaking and listening to Irish, rather than reading and writing. I’d rather this, as it seems more practical, but given the year I’ve taken in Irish, being able to speak a phrase generally means I can read or write it without problem, so I’m not worried about falling behind in that department. I know the program is intensive, so I hope to come a long way in fluency. As for the actual methods, I don’t have many expectations, since I’m open to whatever methods the native speakers think are best. From what I’ve heard, Irish is the language spoken in day to day life in the village, so I’ll be able to get perhaps my best practice outside of the classroom.

I know there will be a couple other ND students there from various classes for at least some of the time, so hopefully I’ll see them a bit. I’ll be leaving on a multi-stage bus trip from Dublin to the Gleann, through Donegal Town and Killybegs. I’ll be staying in a hostel in Dublin tonight, and I don’t know what internet access is like in the Gleann, so I’ll post this whenever I can. I also intend to keep a daily journal in Irish, and will post it here if I have the time. I’ll also try to make a rough English translation, but Irish loses a lot of its complexity and feeling when translated, so it’s more of the bare facts that get conveyed, leaving out some of the nuances.

— Billy McMahon

Post-Script: Oideas Gael does have an internet connection in one room, but it’s taken until the 18th to get it sorted, so I’m posting this a little late. I’m also not sure if there’s a way for me to log in and put this in its proper place, so I’ll just leave it as a reply.

Post-Post-Script: Also, the jet-lag has not cleared up. The sun rises at 4:30 am here.

Reflective Journal Entry 2:

16 Meitheamh 2012 —

Ráinigh mé i Gleann Cholm Cille anocht. Tosaíonn mo rang Gaeilge amárach. Tá mé in iostán le Hellie agus Mel (tá Eli i mball eile). Chuamar go dtí an trá; bhí sé álainn, ach bhí an fharraige fuar. Dhreap mé carracán. Snámhfaidh mé sa fharraige amárach, agus dreapóidh mé na sléibhte go luath.

— B. Mac Mathúna

–

16 June 2012 —

I arrived in Gleann Cholm Cille tonight. My Irish class starts tomorrow. I am in a cottage with Hellie* and Mel* (Eli* is elsewhere). We went to the beach; it was beautiful, though the water was cold. I climbed a great pile of stones (like a natural cairn). I’ll swim in the sea tomorrow, and soon I’ll climb the mountains.

— B. McMahon

*mic léinn Notre Dame (ND students)

Reflective Journal Entry 3:

17 Meitheamh 2012 —

Bhí mo Gaeilge rang céad agam inniu. Tá mé i “Level a dó,” leis an naoú daoine eile. Bhualadh mé le duine nua in Oideas Gael. Is í Miriam mac léinn sa Bhreatain Bheag, ach is as Sasana sí. Oibríonn Jim i Cameroon (san Afraic), leis an rialtas Meiriceánach; is as St. Louis sé. Tá siad an-dheas, agus is maith liom siad. Beidh aithne agam ar duine breis go luath. Fosta, chuaigh mé go dtí an trá le Hellie, Eli, agus Mel inniu, agus shnámh mé sa fharraige (an-fhuar) inniu. Is inniu lá maith… is breá liom Gleann Cholm Cille.

— B. Mac Mathúna

–

17 June 2012 —

I had my first Irish class today. I am in “Level Two,” with nine other people. I met new people in Oideas Gael. Miriam is a student in Wales, though she’s English. Jim works in Cameroon (Africa), for the US government, as he’s from St. Louis. They’re quite nice, so they’re good with me. I’ll know more people soon, too. Also, I went to the beach with Hellie, Eli, and Mel today, and went swimming in the (very cold) sea. It was a good day today… I really like Gleann Cholm Cille.

— B. McMahon

Reflective Journal Entry 4: Journal Task 1-Slang Words

I asked three young (all in their 20s) Irish speakers, including a male teacher and a female teacher, who have a lot of exposure to Irish-speaking teenagers that use slang, for a list of Irish slang words. All were speakers of the Ulster accent, from Donegal to Belfast.

After a (large) list was compiled, I asked a few middle aged and older speakers of both genders about them. I’ve selected four here, as well as two others that are standard words/terms with slang roots or usage. Excluded words include those for rascals, naive people, and whiskey.

The original definitions I was given are included in quotation marks.

breallán – “Dick head” (the meaning I was given, though I can’t find similar Irish words for penis or head that would suggest the origin). An older man told me it was a general word for a jackass. A quick Google search reveals that it’s also a part of Irish flower names. I am not aware of the connection.

cróigeán – A “big, fat, ugly woman.” Potentially offensive if you say it to someone’s face, but several of the younger people said it’s often used. An older woman told me that it was an old word.

glaimín – An “idiot” (standard Irish word for a fool is “amadán” for males and “óinseach” for females, though of course English also has different words for idiot and fool, despite similar meanings). Considered fine for public use by anyone who recognized it, some (but not all) older people and a person from a different dialect (though this could be coincidental) did not recognize it.

–

Béarla – The name for the English language. According to a teacher, it developed from “Béal rá,” the Old Irish for “shit speak” or “shit mouth.” I looked a bit up and found that “bél” was the Old Irish for “mouth,” but haven’t found “rá.” He is an Irish-language teacher, fluent in Irish, and studied the linguistics of Irish in college, though, so there’s likely something there. Most other languages include the root of the ethnic/country name.

poll an bhainc – An ATM (literally: “hole of the bank”). This isn’t slang, but is apparently used as such by many school children. In Irish, “bh” is pronounced as a “w” when followed by a/o/u, and so this term can be slightly mispronounced as “pull a wank” and used as a euphemism for masturbation. “Tá mé ag dul go dtí poll an bhainc” means “I’m going to an ATM” or, jokingly, “I’m going to pull a wank.” It flows particularly well because Irish lacks an indefinite article.

(When the male teacher said “poll an bhainc” for the list, the female teacher walked out of the room.)

Reflective Journal Entry 5: Journal Task 3-Cultural Holiday

I was in Gleann Cholm Cille for the night of June 23rd, which is called Bonfire Night. I spoke with a professor/archaeologist who was giving talks on the subject. He showed me local Stone, Bronze, and Iron Age structures, explaining that Bonfire Day came from the ancient druid culture. He said “Bonfire” came from “Bonefire,” given the accounts of ancient druidic rituals of leading animals into the fire for ritual sacrifice. “Bonefire Night” was always on the eve of the summer solstice. Over time, as Ireland Christianized, the festival was adopted as celebrating the Eve of St. John’s Day, and so was fixed to the night of the 23rd. The countryside is covered by massive bonfires (standing from a point of high ground, dozens were visible throughout the valley) and it is a night of great significance to the local culture.

I asked a local man, and his response was, “We make great piles of wood and tires and light them on fire.”

When asked why, he responded, “For the craic.”

Reflective Journal Entry 6: Journal Task 4-Minorities

Given the fact that I was in a village of 700 people (and perhaps 4,000 sheep), I didn’t have great exposure to many minorities. However, I was able to speak with a local Protestant (a cultural minority in the Republic) and, briefly, with a young black boy. The boy spoke Irish, but the Protestant man did not. Both related the language to their experiences.

The local Protestant man said that he didn’t feel like he was discriminated against in Gleann, given the fact that there’s a Protestant Church and a Catholic Church in town. He said that in the Republic, there’s little to no religious tension in the modern era, and he’s perfectly comfortable. He isn’t unpatriotic, and considers himself Irish (in contrast with most Protestants in the North). However, despite living in an Irish speaking region, he’s always seen the Irish language as something he would be an outsider to. He didn’t have a negative opinion of the language, he simply wasn’t interested in it. Irish culture was his culture, but the language wasn’t an aspect he found all that significant. I should note that I met Irish Catholics who similarly didn’t care for the language. There was a Protestant man from Belfast, raised a British loyalist and taught to hate the Irish language in the Irish classes with me, showing that there has been progress where division over the language is concerned.

The black boy is an interesting case, in that he speaks Irish, and so the only issue he raised directly pertained to the language. In Irish, the word for “person” is “duine” and the word for “black” is “dubh” (pr. “doo” or “doov” depending on dialect). However, the word for a black person is not “duine dubh,” which would be a literal translation. Instead, it is “duine gorm.” “Gorm” is the Irish word for “blue,” and the boy said that he didn’t like being called blue. He didn’t like being called anything, actually, but he was particularly offended by being called a blue person. I spoke to a linguist about this, and explained that it comes from a similar old Irish word that meant someone whose skin has been darkened by the sun. In that way, the predecessor to “duine gorm” was more accurate than just saying “black person,” but with the evolution of the language, few people know this and most just think it means “blue person.”

Reflective Journal Entry 6: Journal Task 6-Views towards the US

The first person I talked to was a man of around thirty. He prefaced his remarks by telling me that most Irish people like America, they just don’t like the things its government does around the world. He expanded upon this by expressing his disdain for the Iraq War and George W. Bush. He says he doesn’t really like Obama personally (he preferred Hillary Clinton), but called Sarah Palin crazy and McCain “scary.” He thinks that the income divide in America is disgusting, and threw out the George Carlin line, “It’s called the American Dream because you have to be asleep to believe it.” He also said that the general stereotype was that all Americans were idiots (similar to the American stereotype that the Irish are all drunks).

I also spoke to an older woman, who didn’t think highly of America’s corporate culture, the influence of money on government, or the attacks on labor unions. She contrasted America’s claim to be the protector of democracy with instances in which it helped overthrow democracies just to replace them with favorable dictatorships, dwelling in particular upon the 1973 CIA-backed Chilean coup that replaced democratically elected Salvador Allende with the brutal fascist dictator Augusto Pinochet, laying much of the blood shed by the latter on the hands of the US government. She compared this to the failed 2002 Venezuelan coup attempt against another democratically elected socialist, Hugo Chávez, which was backed by the US. She’s a citizen of the UK, having been born in the North, and also had a lot of words for Margaret Thatcher that don’t particularly pertain to this assignment.

The third person I spoke with was a young woman. She had a favorable view towards the US in general, but felt that the gun laws were barbaric. Police in the Republic and the UK aren’t even armed, though those in the North still carry guns. She likes American movies and culture, and only other complaint that pertained to America was that Kraft had bought Cadbury and she was worried that they would change their chocolate recipe to save money on ingredients.

I also briefly spoke with a teenage boy from Belfast who fantasized about leaving and going to America. He plans on making it big in New York City as soon as he can get there. I didn’t have this assignment in mind at the time, so I didn’t ask more, but I thought it was of note.

Postcard(s) from Abroad:

Reflection on my language learning and intercultural gains:

In addition to gaining ground in my ability to speak Irish confidently, I was able to gain a lot more knowledge on how the language works. As for my specific goals, I would judge my success as mixed, given the ambition of my goals.1. I am able to communicate with native speakers on a wide range of topics, including news, philosophy, religion (a debate about allowing women to be priests stands out), and history. However, I cannot do so with the same speed as in English; my speaking is at perhaps the speed, and my listening comprehension drops if the person is speaking too quickly. After a month, it was an unrealistic goal to adapt to a native speed, but the effort certainly helped me advance as much as I did.2. I am able to discuss history and philosophy in Irish, but not to the same extent as in English. I have made a point of including vocabulary focused on these topics in my own personal study (or else I’d never be able to talk about communist revolutions or religious debates).3. I certainly can’t think in Irish for days at a time. However, I can manage about an hour, perhaps longer with a dictionary in hand to fill in frustrating gaps. It’s an interesting exercise in an organic approach – learning how to put everything I think in Irish, as a necessity of thinking.After four weeks in the Gaeltacht, I think these results are pretty good. Fluency in such a time would be utterly unrealistic, but the structure is certainly there for me to continue to grow.

Reflection on my summer language abroad experience overall:

Given the gap I had between the end of spring semester and the start of my program, I would say that the saying “If you don’t use it, you lose it” is particularly accurate for second languages. Not using Irish much in the month before my program started made the first week particularly difficult, but then being immersed in the language caused me to develop my language skills at a far faster rate than ever before.My advice would be to approach the language program with dedication, and to avoid speaking your native language as much as possible. If you are in contact with a number of people who do speak English (as I was), setting aside certain hours (especially during particularly social times) in which you only speak the language you are studying is a great way to grow. There really is no fast or easy way to learn a language, you just have to live in it.

How I plan to use my language and intercultural competences in the future:

In addition to my continuing Irish language classes, I am pursuing use of Irish whenever possible, from department events, like conversation tables, to staying connected with students who were in the Gleann with me. Everything from Irish-language meals to keeping up with sports I picked up in the Gaeltacht (hurling is fantastic) are working to keep me motivated.In addition to the personal advancement I feel at learning the Irish language, as discussed previously in my explanation of my preference for the language’s way of thinking, there is certainly an academic potential for my language abilities, as a history major. I’m already taking a class about the history and culture of the Irish language, particularly in the Gaeltacht, and the language could very well end up directly relating to independent history research, particularly through the handling of pre-20th century primary sources.