Name: Anthony Pagliarini

E-mail: apaglia1@nd.edu

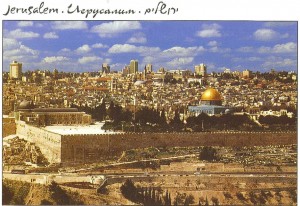

Location of Study: Jerusalem, Israel

Program of Study: “Ulpan” Modern Hebrew Language Course (Level Aleph)

Sponsor(s): Bob Berner

A brief personal bio:

I am a PhD candidate in the department of theology specializing in Sacred Scripture. Prior to coming to Notre Dame I studied at the International Theological Institute in Austria and the Pontifical Biblical Institute in Rome, where I also worked as a tour guide in the Scavi of St. Peter’s Basilica.

Why this summer language abroad opportunity is important to me:

There is a rich are fruitful academic culture of Scripture scholarship in the Land of Israel. While I have studied at length the ancient Hebrew of the Bible, I am unable so much as to order a coffee in the language’s modern form, much less read academic articles. Thanks to the SLA Grant that will change. Classmates and I will spend four weeks in Jerusalem participating in an intensive course in modern Hebrew [an “ulpan”] and being lead on various excursions/immersions throughout the Land. This promises both to increase our knowledge of the many biblical sites and to introduce us to the scholarly world of modern Israel.

What I hope to achieve as a result of this summer study abroad experience:

I hope to sufficiently master a core theological vocabulary in modern Hebrew so as to be able to engage current scholarship. I hope also to acquire a greater knowledge and appreciation of the biblical sites throughout the Land.

My specific learning goals for language and intercultural learning this summer:

- At the end of the summer, I will be able to carry on basic conversation in an academic setting.

- At the end of the summer, I will possess a theological vocabulary sufficient to read scholarly articles with the aid of a dictionary.

- At the end of the summer, I will have laid the linguistic and cultural groundwork for future periods of study in Jerusalem.

My plan for maximizing my international language learning experience:

In addition to daily coursework, my classmates and I will be led on Herbrew-speaking excursions through Jerusalem and the surrounding area by Prof. Avi Winitzer. On Friday evening we will participate in Sabbath dinners with Rabbi Mordechai Machlis, and on Saturday morning we attend synagogue service. During the week we will also visit Yeshivat Har Etzion with Rabbi David Wadler. Lastly, we will have the chance to spend time in the West Jerusalem “Shuk” (marketplace).

Reflective Journal Entry 1:

I was last in Israel on my “studymoon.” As a student at the Biblical Institute in Rome we given the opportunity to spend a spring semester in the Holy Land. After my fiancée and I wedded in South Bend in Early 2010, we headed to Israel for a three months’ stay. As a student—and occasional Busch-league tour guide—in Rome, I’d come to know the city well, and learned by little and by little to “read” its building and streets: Imperial road pavers, pre-Constantinian brickwork, early basilica style, medieval hall church, etc. As my brother joked on his visit: “Everything is Rome is old. But if you want to see what’s really old, ask what’s in the basement.” As like in the church of San Clemente, one could often enter a medieval building, descend below current street level into a 4th century basilica, and descend yet again to 1st century homes. In the Psalms of ascent (Pss 120-134), one hears the call to “go up” to the House of the Lord. Jerusalem, the mountain which “will be raised above the hills” (Is 2:3) is the true mountain of God. And yet for us this “going up” involved a drastic “going down.” Atop the Haram-al-Sharif, one can set foot on the rock of Zion, the foundation of the Holy of Holies from the Solomonic Temple (c. 970 BC) and, if one is willing to believe the tradition, the mountain of Moriah on which Abraham offered Isaac (cf. Gen 22). Often times, the surface of Israel is deeper that the deepest of Rome. During our stay in the Land, my wife and I needed, unfortunately, to embed ourselves in the library of Tantur, reading and writing for much of our stay. Our brief encounters with the Land and its riches were too fleeting, and even when present, we remained separated by the barrier of language, being unable to speak any but the simplest words in either Hebrew of Arabic. We remained gerim (“sojourners”) in the Land, and I’ve longed from the day of our departure to return and immerse myself in the language and the people who continued existence opens a true path of ascent to “go up” to the mountain of the Lord.

Reflective Journal Entry 2:

In early 2000 I landed in Santiago, Chile with only an address of a family with whom I was slated to live for the coming months. I remember, while waiting in the customs line, confusing the word “beso” (“kiss”) with “basura”(“garbage”). My first question upon meeting my host mother came out confusedly and amounted, somehow, to asking her “how many pounds she had” and not, as I intended, “how many years her son had.” In a few months’ time, however, I was reading the news, writing papers, and even taking churrango lessons for a member of a local band. I think my brain has hardened. I feel that, as I often hear Pooh saying when I read to my daughter, “I am a bear of very little brain.” Spanish came very quickly, but even after this first week of intensive classes—and after years of Biblical Hebrew—I can barely muster the words to say the not-quite-all-important phrase “the cake is unique.” (And there isn’t even any cake around for me to say it about!) Along the streets of Santiago, or years later in Rome or Vienna, one could stare up at the store-fronts or look down at the headlines and at least sound out unfamiliar words. The sound alone, even without understanding, gives the word a certain life, a certain nearness, to which meaning can come more quickly. Even the intimidating Herzkreislaufwiederbelebung (“C.P.R.” in German, by the way), opens itself through hearing. Hebrew offers no such luxury. Consonants only. And consonants without vowels are silent glyphs, hard angular silences, impenetrable like the gates and doors which the letters resemble. As a friend remarked, “European languages are written for readers; Semitic languages are like cliff notes for speakers. Unless you already know what it says, the words say little.” The trouble is that I do not “already know what it says,” and I am sure that more than “cake” is being spoken of. I have not yet asked anyone “how many pounds they have,” but if that it the rite of passage to reading the news, writing papers, and taking … shofar (“horn”) lessons, I look forward to offending….

Reflective Journal Entry 3:

The Cathedral of Valencia in Spain possesses what tradition claims is the chalice of the Last Supper. Were the Holy Grail found in our lifetime, it would no doubt be preserved as it is, unchanged. The Chalice in Spain, however, testifies to a different approach to history. The cup has been overlaid with golden handles and jewels. In their own way, these addition preserve the cup’s historicity. While on one hand they veil the full viewing of the simple agate cup, the gold and jewels with which it has been overlaid aid all of those who see it to acknowledge it profound value and show it due reverence. It allows one to see rightly, to “look well” as Virgil admonished Dante. The Christian antiquities of Rome share much with the Valencia Chalice. While as a member o the parish of San Pancrazio, we celebrated our 1700th anniversary. On the spot where the church stands, a young Roman soldier, Pancratius, was martyred for his faith by the troops of Emperor Diocletian. He was buried on the spot, and under the following emperor, Constantine, a memorial was erected on his tomb. Around him grew up a small but significant catacomb and, in time, an early basilica and then the current Renaissance Church. Taken together they form a narrative which allowed me, as a newcomer to the parish, to read, backwards as it were, to the moment of his sacrifice. If it’s not cliché to say so, the accretions of history are crystalline, and they act as a prism to unfold what is seen, showing it forth more clearly that it might have been otherwise been perceived, even at the first. This historical continuity which, in Rome, served the function of a pedagogue, is absent in Israel. Ongoing shifts of power—from Judeans to Romans to Greeks to Arabs and back again—have fractured the storyline. Competing narratives lay claim to the same set pieces and the same characters. Shall we call it Haram-es-Sharif or the Temple Mount? Even those places which are unambiguously tied to a certain tradition lack the “clarity” of the Valencia chalice. The way of the Cross here is a market street, filthy, crowded and noisy. In places where monuments are raised, one feels their newness and their untetheredness form history (and unfortunately sterile architecture. pace O yee sons of St. Francis. ) In a way, however, this is most fitting. “Ox and ass” knew him in the manger, but we did not (cf. Is 1:2). His coming as a babe, and not in the glory we might expect, is the greater part of his self-revelation. “Incense owns a deity night” but its takes a wise man to know this and to acknowledge this. The Incarnation challenges the faithful to see God unadorned, to see him in the midst of a historical circumstance that appears least fitting to his majesty. And I think this is the case still. Jerusalem lends nothing. (If anything the dereliction of places like the Holy Sepulcher obscures the vision!). There is no overlay, no memorial become basilica become Renaissance masterpiece become home parish. All that is well and good, but here, in the absence of any aid, one feels more fully the challenge of a faith begun in a manger.

Reflective Journal Entry 4:

In one of his memorable quips, Winston Churchill said “If you’re going through hell, keep going.” After a few weeks of 5 and often 8 hour days of lecture and several hours of homework, I find myself wanting to “keep going.” (Forgive the grimness of the analogy.) Ira and Rachel, our two teachers, are wonderful at their work. It is a compliment to them that my heads burns with new words. At break-time I wander over to the “mish-mish” (“apricot”) tree. They ripened when we arrived, and, now all but gone, I’ve begun to eye the plums and hold out faint hope that the grapes will mature before July. It is a welcome break among the roses and olive trees that carpet the grounds on Tantur, and without it, the I might be overrun with—to borrow a line from Francis Thompson—the “unhurrying chase and unperturbed pace” of the feat [sic] that follows after. Another few hours. My day is made more interesting, and more fruitful, for being seating in what we’ve affectionately termed “The French Embassy.” Two lovely women from the “Eldest Daughter of the Church” have by-and-by found their way to this place and, what’s more, to our class. Neither has any background in Biblical Hebrew, and at over 60, are further handicapped in the learning of a new language. I have pitiable French, myself, but as I’m seated next to Jacqueline and, yes, Jacqueline, more than a few times each hour we find ourselves hushing something or other: “c’est a dire, ‘acheter.’ Oui, oui.” Augustine said that the task of theology is not complete until one has both learned and communicated that learning. If the same is true of language, I on my way, however poorly. Our progress have been noticeable. We been able to chop our way through a scholarly article and, more importantly, we’re beginning to make sense of the banter in the Israeli “shuq” (“market”). Mish-mish are fine, but chalah, halva, and some good Galilean wine are all the better, especially when I’ve had to navigate the market to purchase them.

Reflective Journal Entry 5:

In the hit Israeli sitcom Arab Labor, the first episode focuses on the politics of the various checkpoints throughout Israel. An Palestinian Arab, himself an Israeli citizen, is frustrated to no end about being stopped every day at the Check point. It’s racial profiling for sure, or so he thinks. “Well, what do you drive?” asks his Jewish Israeli Friend. When he tell shim it’s a Toyota his eyes roll: “That an Arab car” (i.e. a car sold only to Arab countries and not to the state of Israel in former years), “Get a [Range] Rover.” Ten minutes later the show launches into a montage of border crossing scene where the character, in his new car, is waived through, saluted, bowed to, high-fived, and so on. I think Stephen and I have had an “Arab car” the past few days. We’ve been stopped several times, had to unpack the car, go through metal detectors, and answer questions. Little airport-like security booths are set up at what seem to me like arbitrary points in the countryside. Our Avis made no distinction between Israel and the West Bank (a telling assertion, much like the Guatemalans who draw their maps to include the whole of Belize!), but the IDF does make the distinction. We had no idea where the borders were, but when we found ourselves standing under the hot son, sweating in our t-shirts, and making like conversation (about more than “cake” thank God [cf. entry #1], we knew we had crossed something. Next time, we’ll get the Rover. Our trip yesterday took us, among other places, to Tel Arad, a Canaanite city dating from roughly 2900 BC. On the hill top of this settlement in the Judean Wilderness, there is a Judahite fortress from almost two millennia later. Among its ruins is a small sanctuary centered on the “Holy of Holies” in which stood two masebot, or “standing stones,” which figured, according to most, YHWH and his Asherah (his wife!). An interesting testament to the slow development of Israel’s monotheistic faith.

Reflective Journal Entry 6:

The Church of Simeon and Anna is situated on Rav Kook street near Zion square in West Jerusalem. It is one of a small number of Hebrew speaking Catholic parishes in the country. Attending mass there has been a great help in bettering my Hebrew. For one, there are biblical texts with which I’m more familiar, though hearing the New Testament in Hebrew is, well, new. The mass parts, already familiar in English, can be more easily heard and understood. And just this past Wednesday I was able to stay afterward for a long discussion about a document from the Pontifical Biblical Commission on “The Jewish People and Their Sacred Scriptures in the Christian Bible.” Fr. David Neuhaus, SJ a Jewish convert and native Hebrew speaker led the group and was very welcoming to meet “yet another” student from Notre Dame. During the Eucharistic prayer, it was beautiful to hear the blessing over the bread. It is the same blessing before a meal which is used by Jews: “Blessed are you, Lord God, the Eternal King, who brings forth bread from the Earth.” While such a connection is already there is the English text of the mass, hearing the canon in Hebrew unfolded more clearly the deep connections with the faith Old Testament. Praying in a language similar to that of Jesus helps reveal more clearly that deep-seated continuity between the Testaments, from Second-Temple Judaism to the Catholic faith. Catholic Israelis hear this more clearly than I can, but the immersion here has given me a good start.

Postcard(s) from Abroad:

Reflection on my language learning and intercultural gains:

This was my first attempt at learning Modern Hebrew. In years past I’ve had the chance to attend similar courses in Germany and Italy. Therefore, my expectations this time around were reasonable and, I think, well met. One can only learn so many new word in a month’s time, but the “feel” one gets for a language is extremely valuable. It an aspect of “getting in the window” that you cannot get from studying from afar. And while I’m still a novice at Modern Hebrew, I’ve begun to develop that sort of familiarity and ease with the language, both in hearing and speaking, that will serve as a foundation. Hebrew is vastly different than any other language I know, and getting up to speed took considerably longer than it did when I began my studies of Spanish, Italian, or German. Nevertheless, the intensity and length of the program allowed me to meet my goals for the summer.

Reflection on my summer language abroad experience overall:

As mentioned above, the immersion experience is indispensable. It offers a sustained intensity of study that facilitates a quick and more permanent acquisition of the language and it develops an aural ability that cannot be replicated by any other method. The very hearing of the sounds of a language–and there are many strange sounds in Hebrew–produces a level of familiarity that makes learning furhter vocab and syntax all the easier. I would not say that spending a month in Israel has “changed my worldview,” but it creates a certain sympathy and concern for a culture and a people not one’s own. This alone is of great value.

How I plan to use my language and intercultural competences in the future:

I need to read Modern Hebrew as I continue my research in Old Testament. Since returning, four of the five participants, myself included, have continued our study both individually and by enrolling in an online Modern Hebrew course through Hebrew University. It’s a far cry from the experience we had in Jerusalem, but it keeps us honest and moves us ahead, albeit slowly. Were the chance available, through SLA or another source of funding, I would happily take up the opportunity to study again in Israel.