While Notre Dame would flourish in the 19th century, it was not an easy road. Most American educational institutions faced severe obstacles that often led to ruin. John Theodore Wack noted, “Of the fifty-one Catholic colleges which were chartered in all of the United States before 1861, only sixteen were still in existence in 1927. Students, faculty members, and administrators simply could not be found to fill and staff many of the new colleges. Funds were scarce, donors were disillusioned, and creditors were apprehensive; most of the colleges quietly disappeared, leaving an old stone building or two for the wonderment of the children of future generations” [Wack, Notre Dame: Foundations, 1842-1857]. The first few decades of Notre Dame’s history was filled with many of these same hardships.

For the first few academic years, enrollment at Notre Dame hovered around thirty students. Most were preparatory students and only a select few were at the collegiate level. The student body was also highly transient in the beginning, with barley half returning the following term. The faculty was comprised entirely of clergy, whose salary consisted solely of room and board. Most of the faculty were not qualified to teach at the collegiate level and language barriers of the French priests and brothers proved problematic. Tuition, often paid through barter or labor, was a necessity to keep the University running. Therefore, discipline tended to be rather lax in the early years, much to the chagrin of Brother Gatian, who was the outspoken secretary of the Council of Professors.

Sorin and the administration struggled to define the academic curriculum for Notre Dame. The initial plans modeled the French educational system, as that is what they knew. The nuances didn’t translate well into the American Midwest. Sorin then looked to other American Universities for guidance and settled on modeling a curriculum after that of St. Louis University. However, the American pioneer boys craved a more practical education and were not as drawn to the classics as their East Coast contemporaries may have been. While the classics were offered, most students took the “English Course,” which taught business skills such as bookkeeping, which the students found to be more pragmatic. It took a while to get the right combination and the appropriate faculty, but more and more students were returning to their studies at Notre Dame in the late 1840s and early 1850s.

Another continued sources of contention was the dynamics of personalities between Fr. Sorin, Vincennes’ Bishop Hailandière, and Superior General of the Congregation of Holy Cross Rev. Basil Moreau back in Le Mans, France. Sorin still envisioned Notre Dame being the epicenter of a national Catholic educational system. Hailandière was not happy that Sorin was looking to expand outside of the diocese. Moreau was not happy with Sorin’s lack of bookkeeping and, like many others, was concerned over the debts Notre Dame had accrued. Moreau also did not understand the American cultural differences Sorin faced and he was not a fan of the liberties Sorin was wont to take. The physical distance between them bred misunderstandings, and Sorin often acted impulsively on opportunities because he did not have time to get permission from France. Despite all of the conflict, Moreau never gave up on Sorin or the Notre Dame dream, although at times both parties were ready to throw in the towel.

Also in the mix of cantankerous personalities was the return of Rev. Stephen T. Badin to Notre Dame in 1845. Badin approached Sorin with some investment opportunities in exchange for a pension in his old age. Badin had some land in Kentucky, which he offered to Notre Dame to help with the financial struggles. However, when Sorin sold the land at a much lower price than what Badin thought they were worth, the feud between the two head-strong priests began. Badin began publicly criticizing Sorin and the administration at a time when the fledgling Notre Dame could ill-afford bad press. Sorin retorted to Badin, “In two words, no one has done more good for the institute than you, Monsieur, and no one has done it more harm” [Sorin to Badin, quoted in Wack].

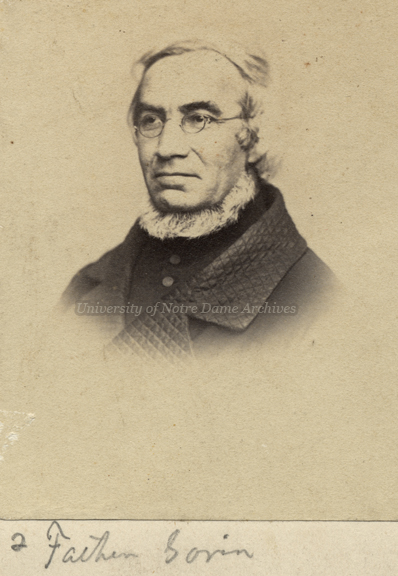

Badin’s attacks and Moreau’s concerns weren’t without some founding, however Sorin often wished to state his case in person to eliminate further misinformation. Yet when Father Sorin left Notre Dame for months on end to attend to business in France, Vincennes, Indianapolis, Kentucky, or New Orleans, those left in charged at Notre Dame often floundered. “There should be no question: Father Sorin was the essential ingredient in Notre Dame du Lac. Without his yeast, there would have been no growth. Until some other person as capable as he could come forth, Father Sorin was necessary to the existence of the institution which he had founded” [Wack].

Sorin also was contending with outside forces in the heavily Protestant community in which the Catholic Notre Dame resided. Sorin felt that the outsiders regarded Notre Dame with an unsure and scrutinizing eye, looking for any excuse to tear down the new Catholic institution. In spite of the many crises he faced, Sorin maintained Notre Dame as best he could with a facade of success, stability, and permanence. Any rumblings in the town square of Notre Dame’s financial struggles or battles with disease could adversely effect enrollment and thus the future of Notre Dame. On the other hand, Sorin believed that “in America, one must attract public attention to achieve success” [Wack]. He worked hard to keep Notre Dame in the spotlight, even if it meant going further into debt. While the return on investment would be difficult to calculate for the time, Sorin splurged with such purchases as Dr. Cavalli’s museum collection in 1845 and America’s largest carillon in 1856.

Notre Dame was not immune from natural disasters. Fires were relatively common and often disastrous. In 1849 the Manual Labor School was completely destroyed, convincing Sorin to take a gamble and send a company of brothers and a few townspeople to join the California gold rush. Their expedition was unsuccessful in finding gold, and sadly lead to the death of Brother Placidus and the desertion of George Campeau and Brothers Stephen and Gatian. The move also furthered the chasm between Moreau and Sorin, as Sorin acted without permission from the Motherhouse.

In 1855, the original log cabins near Old College, which were then being used as stables, burned and much of the farm equipment and storehouse were destroyed. Fortunately, the fire remained contained to that area and did not touch the rest of the campus buildings. It most likely would have been the end for Notre Dame if campus were destroyed at that point in history.

Disease was a such constant at Notre Dame with annual summer outbreaks of malaria and cholera that Sorin considered several times abandoning the site for less toxic land. Sorin and the administration figured the problem arose from the marshy lakes and stagnant water. They tried unsuccessfully to lower the water levels by digging trenches, but the real issue was a dam downstream near the St. Joseph River owned by Mr. Rush. Legal actions and attempts to buy the land from Mr. Rush were futile. He refused to budge. In 1854, an epidemic of typhoid fever ran through Notre Dame and Saint Mary’s Academy in Bertrand, claiming over twenty victims, mostly faculty and staff. To quell panic in the community, burials were held at night and information about the crisis was kept quiet.

In 1855, Rush finally conceded to sell his land to Notre Dame, but when he backed out at the last minute, Sorin sent a group of the strongest men at Notre Dame to go bust up the dam themselves. Rush then went through with the sale of his land. Notre Dame’s lakes receded and the disease dissipated.

While Sorin and Notre Dame faced many hardships, they also garnered much success. Notre Dame greatly benefited from the Catholic networks in American and in France. While some opportunities turned contentious, Sorin’s reputation as successful “college-builder” opened many doors. In 1856, Bishop O’Regan of Chicago struck a deal with Sorin that all Chicago parochial schools would be under the direction of the Congregation of Holy Cross.

The purchase of Mr. Rush’s land near the St. Joseph River in 1855 enabled Sorin to move the Holy Cross Sisters from Mishawaka and Saint Mary’s Academy in Bertrand closer to Notre Dame. Around the same time, an incredibly generous donation from William Phelan of his land near Notre Dame helped to keep the institution afloat financially.

The 1850s brought an influx of immigrants to the United States, primarily people from Ireland and Germany who were fleeing famine and civil war in their homelands. Many of those immigrants were Catholic and were settling in the Midwest. The advent of the railroad through South Bend at this time would greatly help Notre Dame to grow its enrollment. Greater enrollment necessitated expansion of Main Building in 1865-1866. Amid typical Notre Dame pomp and circumstance, Notre Dame was consecrated on August 15, 1866, and newspaper reported that “the ceremony will eclipse everything of the kind which has ever taken place in the United States.”

The foundations that Fr. Sorin established in the 1840s and 1850s enabled Notre Dame to persevere through inevitable crises. Like most other American institutions, Notre Dame struggled during the Civil War. Many members of the Congregation of Holy Cross served as chaplains, notably Rev. William Corby, who was attached to the Irish Brigade, and Rev. Joseph Carrier, who was at the deathbed of General William Tecumseh Sherman’s son Willie.

At any earlier point in history, the Great Fire of 1879 may well have been the end for Notre Dame. However, just days after the fire, with most of campus destroyed, Scholastic writers reported, “we feel that there is no reason to give way to discouragement. No, we cannot bring ourselves to believe that the sun of Notre Dame has set. Let the thousands of loving children whom she has sent into the world within the past quarter of a century — let the devoted friends whom she counts in all parts of the country but rally to her relief, and we have every reason to feel confident that the good work which she has been doing in the past will be continued in the not distant future” [Scholastic, April 26, 1879 issue, page 536].

Father Sorin’s vision, faith, and determination was infectious. In an 1852 circular letter, Sorin reminisces about the first time he saw Notre Dame ten years earlier. His passion for Notre Dame, which he saw as divinely guided, and his dogged determination in its success is palpable:

“At that moment, one most memorable to me, a special consecration was made to the Blessed Mother of Jesus, not only of the land that was to be called by her very name, but also of the Institution that was to be founded there; –an humble offering was presented to her of its modest origin and its destiny, of its future trials and labors, its successes arid its joys. With my five Brothers and myself, I presented to the Blessed Virgin all those generous souls whom Heaven should be pleased to call around me on this spot, or who should come after me. From that moment I remember not a single instance of a serious doubt in my mind as to the final result of our exertions, unless, by our unfaithfulness, we should change the mercy from above into anger; and upon this consecration, which I thought accepted, I have rested ever since, firm and unshaken, as one surrounded on all sides by the furious waves of a stormy sea, but who feels himself planted immovably upon the motionless rock. Numerous as have been the dangers of all sorts to which we have been exposed, the obstacles and difficulties we have had to meet and overcome, the sufferings and crosses we have had to undergo, the various assaults and the persevering efforts of hell to destroy the Community in its infancy; though often annoyed by the ill-will of open foes without, and more than once betrayed by false friends within, I say it with a sentiment of deep gratitude, of every one of these trying occasions our Blessed Mother has invariably availed herself to show us her tender and powerful assistance.” [Sorin Circular letter, 12/08/1852]

Sources:

The University of Notre Dame du Lac: Foundations, 1842-1857 by John Theodore Wack

Scholastic

Sorin Circular letter, 12/08/1852

PNDP1052-1840o&x

GSBA 1/01

PNDP70-Sa-3