On February 6, 1814, Edouard-Frédéric Sorin was born and baptized in the small town of Ahuillé, France. He was born the seventh of nine children into a relatively well-to-do Catholic farming family, a generation or so after the bloody French Revolution. The Revolutionaries heavily persecuted the Catholic Church, sending thousands of priests to the guillotine or exile. However, by the time Sorin’s birth, France had begun mending fences with the Church. In this resurgence of peace, Sorin saw an opportunity for leadership to rebuild the Catholic Church in France through the priesthood, a calling he had since childhood.

In 1834, at St. Vincent’s Seminary in Le Mans, France, Sorin met the charismatic professor Rev. Basil Moreau, who was on the brink of founding the Congregation of Holy Cross. Sorin was ordained on May 27, 1838, and assigned to be a parish priest in Parcé-sur-Sarthe. A year later, Sorin jumped on the opportunity to join Moreau’s new ambitious order that focused on education and foreign missions, rejoining the novitiate in Le Mans. On August 15, 1840, Sorin officially took vows in the name of the Congregation of Holy Cross.

At the appeal of the Célestine Guynemer de la Hailandière, Bishop of Vincennes, for clergy in a predominantly French Indiana, Moreau offered to send six brothers led by a young priest – Edward Sorin. As would echo throughout Sorin’s life, Sorin saw this assignment as a direct mission from God and he threw himself into the idea with unabashed zeal. Before he even left French soil, Sorin declared his allegiance to America, which to him was a relatively blank canvas upon which he could help build the Catholic Church:

“How happy I am to be able to assure you that the road to America stands out clearly before me as the road to heaven. … Henceforth I live only for my dear brethren in America. America is my fatherland. It is the center of all my affections and the object of all my thoughts. … At the present time I see clearly that our Lord loves me in a very special manner as has been told me many times.” [Sorin to Hailandière, summer 1841, as quoted by O’Connell, page 52.]

The group left France on August 5, 1841, the Feast of Our Lady of the Snows, a coincidence not lost on Sorin a year later, and headed to New York. Hailandière arranged for Samuel Byerley to meet the group in New York, who remained friend and benefactor to the Community throughout the years. From there, they took an arduous journey primarily across a series of canals and rivers to Vincennes, with none of them knowing English.

Fr. Sorin and the Brothers were assigned to St. Peter’s parish near Washington, Indiana, tasked to build a novitiate for the Brothers of St. Joseph. The hope was that novices would serve as teachers within the diocese. A poor harvest, lack of monetary resources, and struggles between the strong personalities of Sorin and Hailandière led both of them looking for new opportunities. As it happened, the Diocese of Vincennes had in its possession a tract of land in Northern Indiana, near the south bend of the St. Joseph River.

The land now occupied by the University of Notre Dame has a long tradition of being a place of Catholic missions. French Jesuit Rev. Claude Allouez founded a mission along the lakes and christened it Sainte-Marie-des-Lacs. Rev. Stephen T. Badin, the first priest ordained in the United States, came to the area at the request of Leopold Pokagon, leader of the Potawatomi, for Catholic priests to minister to his people. He bought the parcels over time in 1830-1832. As one who was often negotiating real estate deals, Badin sold the land and a few dilapidated buildings to the Diocese of Vincennes in 1835 for $751 with the condition that it be used for a school and orphanage. Rev. Ferdinand Bach was given the task to build such institutions on the land in 1840. His failure to do so and abandonment of the post timed perfectly with Sorin’s ambition to build a college in America.

Perhaps as a way to physically distance himself in Vincennes with Fr. Sorin, Hailandière offered the northern land to Sorin as a place for him to build his envisioned college, giving him only two years to do so. Sorin was so determined to make it a reality that he made up his mind to leave Vincennes in the middle of a harsh Indiana November without first seeking permission from Fr. Moreau.

Fr. Sorin and seven of the Brothers – Mary (later changed to Br. Francis Xavier), Gatien, Patrick, William, Basil, Peter, and Francis – left Vincennes on November 16, 1842, and their 250 mile trek was not an easy one. They only gained five miles on the first day in the cold, snow, and high winds. Impatiently, Fr. Sorin and four of the Brothers went ahead of the other three, who were slower with all the gear loaded on a broken-down ox-drawn wagon. Eleven days later, Sorin and the four Brothers arrived in South Bend. Alexis Coquillard, nephew of the South Bend merchant of the same name, greeted the band and showed them to their new home that same afternoon.

“Everything was frozen, and yet it all appeared so beautiful. The lake, particularly, with its mantle of snow, resplendent in its whiteness, was to us a symbol of the stainless purity of Our August Lady [Our Lady of the Snows], whose name it bears; and also of the purity of soul which should characterize the new inhabitants of these beautiful shores. … Yes, like little children, in spite of the cold, we went from one extremity to the other, perfectly enchanted with the marvelous beauties of our new abode. Oh! may this new Eden be ever the home of innocence and virtue! There, I could willingly exclaim with the prophet: Dominus regit me … super aquam refectionis educavit me! [“The Lord guides me … beside still waters”; Psalm 23] Once again in our life we felt then that Providence had been good to us, and we blessed God with all our hearts.”

The great dreamer continued,

“While on this subject, you will permit me, dear Father, to express a feeling which leaves me no rest. It is simply this: Notre Dame du Lac has been given to us by the Bishop only on condition that we build here a college. As there is no other within five hundred miles, this undertaking cannot fail of success, provided it receive assistance from our good friends in France. Soon it will be greatly developed, being evidently the most favorably located in the United States. This college will be one of the most powerful means of doing good in this country, and, at the same time, will offer every year a most useful resource to the Brothers’ Novitiate; and once the Sisters come – whose presence is so much desired here they must be prepared, not merely for domestic work, but also for teaching; and perhaps, too, the establishment of an academy. … Finally, dear Father, you may well believe that this branch of your family is destined to grow and extend itself under the protection of Our Lady of the Lake and St. Joseph. At least such is my firm conviction; time will tell whether I am deceived or not.”

[Sorin to Moreau, December 5, 1842]

The men quickly got to work clearing the land to build a new log chapel, which opened on March 19, 1843, the Feast of St. Joseph. Sorin nearly exhausted his finances buying lumber and bricks with the hopes of building a grand main building. Unfortunately, the hired architect showed up months too late for it to be open in 1843. In the meantime, the Community built the sturdy brick Old College so that at least the Brothers wouldn’t have to spend another drafty winter in the log chapel.

In the summer of 1843, more support personnel came from Le Mans – “two priests, Fathers Francis Cointet and Theophile Marivault; a seminarian, Mr. Gouesse; one Brother, Eloi; and four Sisters, Mary of the Heart of Jesus, Mary of Bethlehem, Mary of Calvary, and Mary of Nazareth” [Wack]. Each had his own talents, which contributed greatly to the growth of Notre Dame.

Among the first students to arrive were Theodore Alexis Coquillard and Clements Reckers in 1842. Others slowly trickled in and Notre Dame had 18 students enrolled by June 1844, although many didn’t stay long enough to earn a degree. Ever ambitious, Sorin saw Notre Dame as a central beacon for the influx of Catholic immigrants in America. Notre Dame would be the model for all levels of Catholic education – elementary, preparatory, collegiate, seminary, vocational. He envisioned satellite campuses and most definitely institutions for girls and women. Notre Dame applied for a charter with the State of Indiana to grant degrees with the authority of a college and formed an administration. On January 15, 1844, Indiana chartered Notre Dame as a university, even though it would be some time before Notre Dame would have a strong collegiate student body and faculty.

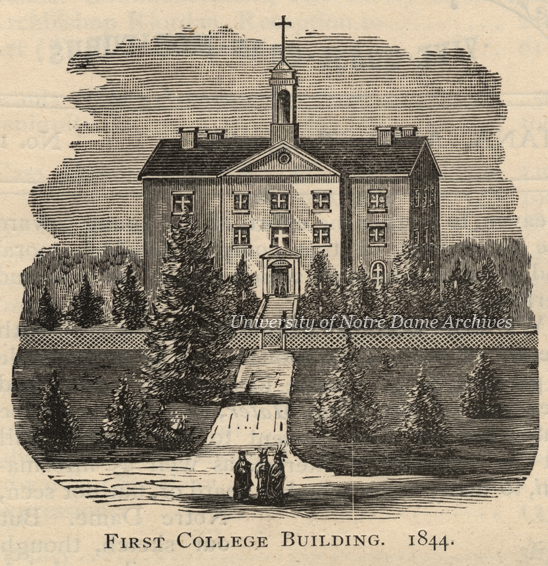

Mr. Marsile, the main building architect, finally arrived in August 1843. Sorin was running out of funds, but knew that if he delayed building, it might never happen. He boldly decided to start the project right away. Fortunately, the winter of ’43 wasn’t as harsh as the year before and “[b]efore the first snow fell, the walls were raised and the building was partially under roof. The remainder of the work, particularly the inside plastering and preparation of the rooms, was left to be finished in the spring. By June, 1844, the main college building was complete. This first main building did not include the two wings which had been planned; these were left to be added in later years” [Wack]. Notre Dame was well on the way to success, although not without the obstacles and growing pains that many American colleges faces at this time.

Sources:

Chronicles of Notre Dame du Lac by Rev. Edward Sorin

Edward Sorin by Marvin O’Connell

The University of Notre Dame du Lac: Foundations, 1842-1857 by John Theodore Wack

The University of Notre Dame: A Portrait of Its History & Campus by Thomas Schlereth

Sorin to Moreau, December 5, 1842

Scholastic

GNDL 21/08

GCSC 04/30

GCSC 04/32