In June of 1894, Scholastic editor James J. Fitzgerald wrote a lengthy article about the Catholic Archives of America housed at the University of Notre Dame. Fitzgerald interviewed longtime Notre Dame History Professor and Librarian James Farnham Edwards about his life work of collecting vast amounts of manuscripts that document the history of the Catholic Church in America.

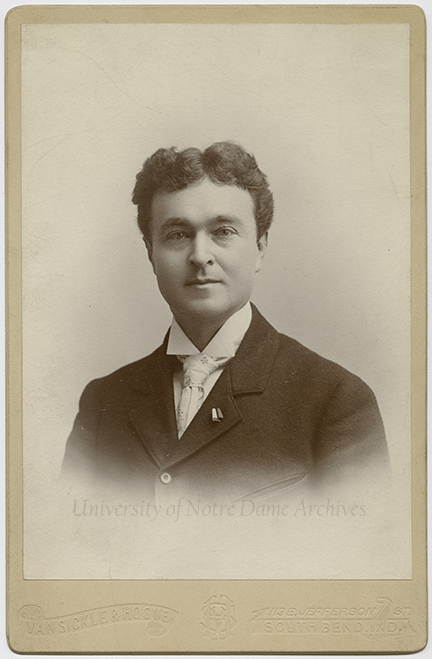

Photo by Van Sickle and Hogue, South Bend.

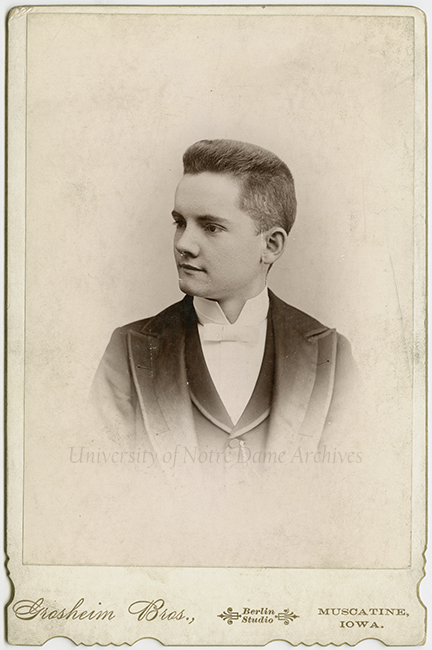

Originally from Toledo, Ohio, Edwards came to Notre Dame as a Minim at the age of 9 in 1859. Staying at Notre Dame throughout his schooling, Edwards was retained as a history professor and librarian for nearly 40 years, until a stroke befell him in 1909, ultimately leading to his death in 1911. Since his teenage years, Edwards had a fascination with the history of the Catholic hierarchy in the United States and began actively collecting materials and across the country that would become known in the 19th century as the Catholic Archives of America. His reputation as a collector of Catholic materials grew immensely as well. In the interview below, Edwards recalls the moment that passion for preserving history first sparked.

The Notre Dame Archives continues Edwards’ work by actively collecting materials that document the life of the Catholic Church and her people as lived in the American context. Archivists succeeding Edwards have since finished arranging and describing his collections; they are available to researchers and have been utilized by many scholars for over one hundred years. Below is the article published in the June 30, 1894, issue of Scholastic. It gives much valuable insight into the workings of the Notre Dame Archives during the 19th century.

_____________________________________

The Catholic Archives of America

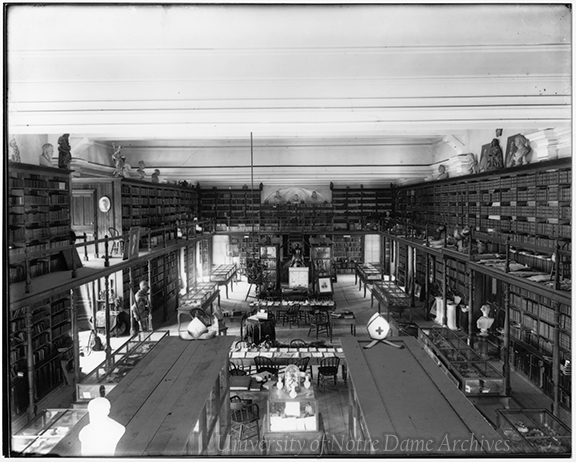

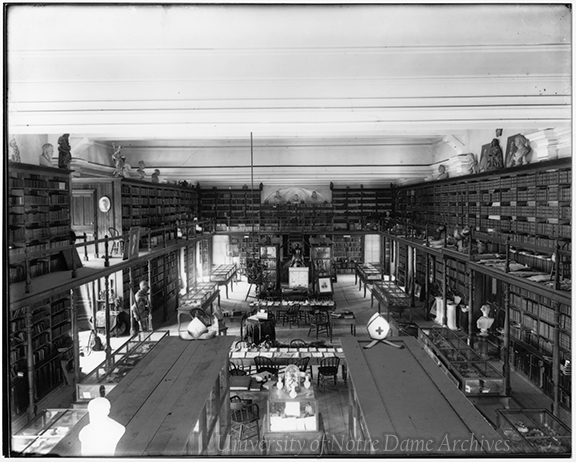

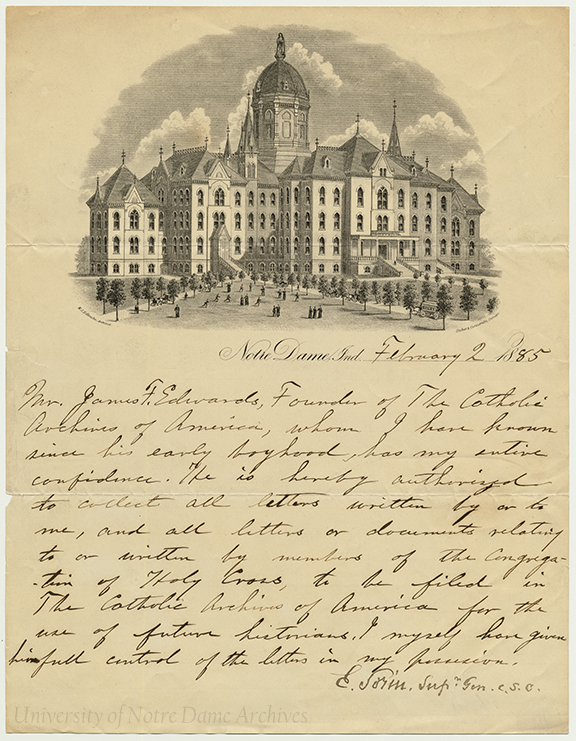

THERE are frequently being carried on about us, quietly and unobtrusively, great and good works by unassuming and self-sacrificing persons who labor, not for reward or fickle approbation of a generation, but who aim at conferring a benefit upon future generations. Such a work is now being done at Notre Dame. The SCHOLASTIC reporter had observed, from time to time, in the Express Office boxes marked “valuable documents”; and rumors had reached him of the great numbers that were gradually and quietly being brought together to form the Catholic Archives of America.

If Cardinal Gibbons, Archbishop Elder, Archbishop Janssens, Monsignor Seton, or Bishop Spalding were accosted with regard to the Catholic Archives, any one of these worthy prelates would inform us that these archives could be found in a remarkable collection of manuscripts, letters and other documents at Notre Dame, Indiana, and the bringing together and forming a collection of these priceless papers was due to the untiring zeal and disinterested labor of a layman — Professor James F. Edwards.

If the questioner, however, came to Notre Dame and casually asked for the same information how few could really tell him of these historical treasures, and that one of our own honored Professors had devoted his time unceasingly to the collection and preservation of numberless papers, all referring to the history of the Catholic Church in America.

The SCHOLASTIC reporter called on Professor Edwards quite recently for the purpose of gaining some idea of the nature, present condition and future outlook of the Catholic Archives. He found this gentleman seated in his study busily engaged in arranging some manuscripts. An interview was kindly granted, and the reporter, encouraged by his pleasant reception, did not hesitate to launch into an endless number of questions.

“Professor,” remarked the reporter, “I heard that you have collected together a large number of valuable documents of great historical value relating to the Catholic Church in America.”

“Yes, it is true,” replied the Professor; “and to give you some idea of the great number of documents, I will take you through the Archives.”

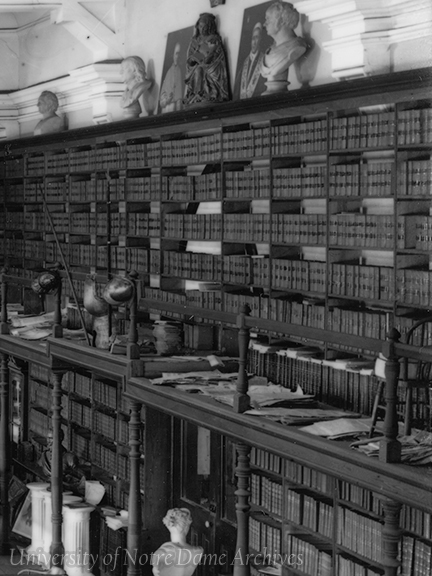

The reporter was soon ushered before shelves upon shelves of documents neatly filed for reference, secretaries filled with letters, walnut cases gorged with manuscripts, and baskets heaped with papers and historical references, but untouched and not arranged. Picture the astonishment of the reporter, who expected to see some few hundreds of these valuable papers, when he gazed on thousands before him.

“You see I have undertaken a laborious task,” said the Professor. ” The collection before you represents the work of a quarter of a century and was gathered together only through untiring endeavor and continuous labor. Be seated, and I will show you some of the documents.”

Ensconcing himself in a large arm-chair, the reporter felt that he was ready for any surprise; but when letters written by saintly clergy, who were the pioneers of the Church in America, and documents written in French, German, English and Spanish, colored with age, were laid before him, his amazement knew no bounds. Here were letters of Archbishops Carroll and Hughes; Bishops Brute, Flaget, Du Bois and hosts of other prelates; manuscripts by Badin, Gallitzin, Nerynx and De Smet.

“How did you ever bring such a remarkable collection together?” asked the reporter finally, when his astonishment had abated to some extent.

“Well, it has been a life’s work with me. When a young boy I was one day in a room where much rubbish had accumulated, which was about to be removed. Amongst the heaps of paper I discovered several documents in Father Badin’s handwriting, also letters of Bishop Cretin, Father De Seille, and several other missionaries. I preserved these letters, and from time to time chanced upon other documents which I added to my collection. I conceived the idea that the best way to gather and preserve this historical matter would be to have a place where it would be collected entire, and easier access would thus be insured to it than if they were scattered throughout the country in the different dioceses. The bishops find it difficult to supply their diocesan churches with priests, and can therefore ill afford to designate men to do this special work. My plan to locate the Catholic Archives at Notre Dame — a place centrally located, and away from the dust and smoke of a large city — was heartily approved by all the clergy who were informed of it. For nearly twenty-five years I have been accumulating this treasury of historical matter.”

“Have your efforts been aided to any great extent?” interposed the reporter.

“Yes. I appreciate the generous assistance received from many quarters,” replied the Professor. “I find that most of the hierarchy realize the vastness of the labor and its invaluable importance to future history. Among these documents you may see the names of popes, cardinals, archbishops, bishops, priests, generals, lawyers, doctors, nuns, etc.; documents from the Propaganda, American College; in fact, all the most eminent clergy of the United States, Canada, Mexico and Cuba are represented here. The Carmelites, Visitation nuns, Ladies of the Sacred Heart, Dominicans, Franciscans, Sisters of Charity — and the many other orders of Sisterhoods, besides learned Jesuits, Redemptorists, Lazarists, Benedictines, and others, have contributed. Among laymen, Doctors Shea, Brownson, Clarke, Onahan, Egan, and Messrs. McMaster, Hickey and Ridder have been specially liberal and presented much valuable material to the archives.”

“These papers must cover a great period of time, do they not?”

“Some of them date back two and three centuries, but the greater number have reference to the early history of the United States, and the early missions in Indiana, Michigan, Illinois, Texas, Kentucky, Oregon, Colorado, etc., etc., during the last fifty or sixty years.”

“Have these documents been used much in historical work?”

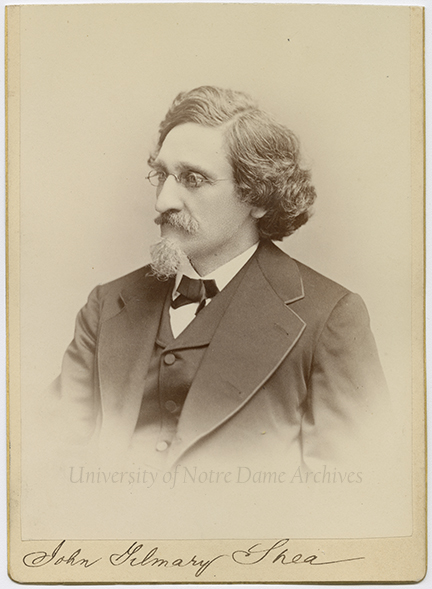

“No; but this was due to the difficulty in discovering the whereabouts of most of the papers and securing them. John Gilmary Shea drew on the archives somewhat; but the historians of the future are the ones who will derive the benefit. John Gilmary Shea deeply appreciated the great good to be realized from the archives. Here are some of his communications on the subject.”

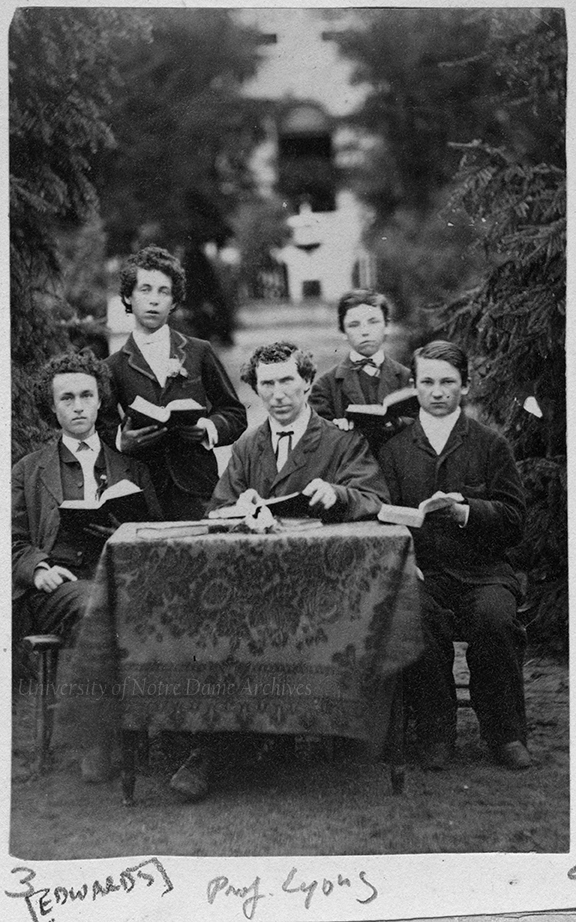

Photo by Hill, Elizabeth, New Jersey.

Professor Edwards placed before the reporter a large number of letters written by the great historian, and with permission the reporter inserts the following quotations:

MY DEAR PROFESSOR:

Your wonderfully kind loan has arrived safely, and is a deluge of historical material, a perfect mine of facts, estimates and judgments. Many of these letters have been in several hands, and how little they have made of them! There are some where every line is a volume to one who understands: De Courcy had some of them. Bishop Bayley had them for years, Archbishop Hughes also had them. I recognize by Bishop Bayley’s endorsements some of the Brute papers so long in his hands and part of which perished by fire.

You possess in what you have gathered more material for a real history of the Church in this country during the present century, than was ever dreamt of. Your own zeal and labor as a collector, guided by intelligent love of Church and country, has been rewarded by great results. Yet I hope that it is only a beginning. I recognize more thoroughly now what you have done and, properly supported, may still do . . . You have created a new line, and your zeal has saved much from decay and destruction.

“Dr. Shea,” continued the Professor, “contemplated a long visit to Notre Dame, and hoped to make a thorough examination of the manuscripts; but his sad and sudden death put an end to his cherished plans.”

When asked if the manuscripts were open to general use of writers, the Professor said: “No; not for the present. Such a privilege would make the presentation of the archives impossible. The great amount of papers and letters not yet assorted makes it impossible for a writing public to handle them. Besides, there are many documents of a personal nature which cannot be seen until all now living have passed away. The archives are for future generations. I spend several hours daily in arranging the manuscripts and filing them for reference. I could employ five or six persons for an indefinite time in assorting the papers. The writers who will be permitted access to the archives must be pursuing a special historical work, and have the recommendation of the ecclesiastical authority of their diocese. However, any information asked of me in regard to historical matter, dates or facts, is willingly given.”

When asked if he thought that further material would be added to the archives, the Professor was not slow to state the hopeful outlook for more valuable manuscripts. He said: “Now that the plan of collecting the archives and centralizing them has become known, all true friends of Catholic history will aid and further this work. Many valuable documents are promised me which will be arrive after the death of the authors. I am constantly receiving letters and papers for the archives, and I find the clergy’s appreciation of the work increasing with time.”

When the inquiry was made of Professor Edwards whether much historic material had been destroyed or lost, a look of deep regret took the place of his usual pleasant expression, and he replied: “Yes: there are too many cases where priceless documents were destroyed by the carelessness, ignorance and neglect of Catholics themselves. Rome had to pay as much for the last of the Sibylline books as for them all; and I find the story repeated daily with reference to valuable writings.

“Bernard Campbell, an historian who began a Life of Archbishop Carroll in the Catholic Magazine, collected and studied for years. He obtained many documents from Bishop Fenwick, the second Bishop of Boston, and the Rev. George Fenwick, both interested in historical matters. Mr. Campbell gathered together a remarkable collection of material concerning the Church in this country. At his death his wife placed these manuscripts in a trunk, and as she travelled much, she carried the papers with her; and preserved them for a considerable length of time, expecting to find someone who would realize the value of the papers and endeavor to procure them. But, unfortunately, no interest was taken in the collection, and she burned them.

“Another case of occurred in New Orleans when the Federal troops threatened to destroy that city. Most of the papers of Bishop Peñalver, Bishop Dubourg, and others, were concealed in a fireplace and bricked up. After General Butler had been in possession of New Orleans for some time the wall was removed, and then it was found that no one had thought to close the chimney at the top; the rain had poured down and the papers were a mass of pulp.

“I had occasion, sometime ago, to visit Vincennes to look up some records of Father Gibault, who did so much towards inducing the settlers of the West to declare for the United States. I then learned that Bishop de la Hailandière and his illustrious nephew, Father Audran, had collected a vast amount of material written by the early missionaries of Indiana, and placed them away — in the archives of the Cathedral; but later on some persons, not knowing the value of the manuscripts, consigned the papers to the fire, thus depriving historians of a great amount of interesting documents.

These are but a few of the many instances where priceless historic matter was destroyed through ignorance and vandalism. But while I think with deep regret of the losses to history, yet the amount of material that exists is encouraging; and I hope to see the time when all the manuscripts referring to Catholic Church history in the United States will be gathered in the Catholic Archives of America to aid and further the work of the John Gilmary Sheas and De Courcys of the future.

J. J. FITZGERALD.