Since the beginning of collegiate football when Princeton played Rutgers in 1869, the game has been constantly evolving. One aspect of the game that was in flux for many years was passing. While lateral and backward passes or pitches were legal, anything that crossed the line of scrimmage was against the rules. In March 1888, over a month before the second-ever Notre Dame varsity game was played, Scholastic reprinted an abridged list of American football rules from Century, which described the techniques of sequential lateral passes, reminiscent of the 1982 Stanford vs. California game (minus the marching band in the end zone):

“Passing” the ball, or throwing it from one to another, is another feature of the game. Hardly any combination of team-playing and individual skill is more noteworthy than the sight of a first-rate team carrying the ball down the field, each player taking his turn in running with the ball, and, when hard pressed, passing it over the head of an opponent to one of his own side, more fortunately situated, who carries it farther. Considering that the egg-shape of the ball makes it the concentrated essence of irregularity, that only the most skilful player can even hazard a guess at the direction which it will take after a bound, and that an error of but an inch in the direction of a throw may carry the ball a dozen feet away from the place at which it was aimed, one may be pardoned for admiring the certainty with which individuals and teams make each point of play and combine them all into an organized system. A “pass forward” is not allowed, and is a foul; the ball must be thrown straight across the field, parallel to the goal-line, or in any direction back of that line [Scholastic, 03/10/1888, page 391].

Sadly, the rough style of play and lack of much protective equipment led to serious injuries on the gridiron – from cuts to broken bones and even death. Many colleges began banning the football programs. The public, however, loved the game and flocked to newly built stadiums to see the contests. In December 1905 as part of an effort to try to save football, President Theodore Roosevelt called upon college administrations to unite and come up with standards that would make the game safer. One of the recommendations that eventually came out of the committee was to open up the game with the forward pass.

Once it became a legitimate strategy, the forward pass slowly made its way into the playbooks across the country for the 1906 season. Saint Louis University is credited with being the first to legally and successfully use the forward pass. In recapping Notre Dame’s first game of the season against Franklin, Scholastic was disappointed not to see the forward pass immediately used on Cartier Field:

The new rules were much in evidence, especially in the way of penalties, as the Varsity was penalized at least 100 yards during the game. The rooters did not get a chance to see the new game tested, as straight football was used by the Varsity; the much-talked of forward pass and short kicks did not show up as it was hoped. During the first half, and in fact most of the time, Notre Dame resorted to the old style of play [Scholastic, 10/13/1906, page 75].

Notre Dame and Army had both sporadically used the forward pass to success well before 1913. However, there were still a lot of disadvantages to the forward pass such as penalties for in completions and much higher risks of turnovers than running the ball. While many football programs were aware of the pass and occasionally used it, it was still a rarity in the game. Proponents of the traditional style of football tried to revoke the forward pass from the rule book. However, by 1913, many of the penalties and restrictions were removed and it came time for coaches and players to develop their athletic skills and try their hand at using the open game to their advantage.

The Eastern teams tended to stick with the old-style of play while the Western schools were more comfortable with the open passing game. Since there had been little interconference play, Harvard, Yale, and Army were apples and oranges to Michigan, Wisconsin, and Notre Dame. No one was really sure how to compare them to one another. The Western schools also had the disadvantage in that many East Coast sports reporters were biased toward the Eastern schools and their style of play.

Since 1887, Notre Dame had worked her way up to the top of the Western Conference, even nabbing the title in 1909. Louis “Red” Salmon (1902) and Harry Miller (1909) garnered third team All-America nods before Gus Dorais became the first Notre Dame player to earn first team recognition in 1913. In 1912, the Notre Dame football team chalked up its first undefeated, untied season, under the helm of Coach Jack Marks, a Dartmouth man who taught the Notre Dame squad Eastern tactics. While Marks never lost a game in his two years, the record was against light schedules that brought in little revenue. The administration, students, and alumni knew Notre Dame athletics could do better.

In this vein, Notre Dame hired the talented and much sought-after Jesse Harper of Wabash College in December 1912. Harper, who played under Coach Amos Alonzo Stagg at the University of Chicago, would assume his post of Athletic Director and coach of all varsity sports at Notre Dame in September 1913. In those nine months, he worked hard on behalf of the Blue and Gold to schedule the most competitive opponents possible and to fill the bleachers, and thus the coffers. Due to conflicts within the Western Conference, Harper sought to schedule teams outside of the Midwest, which proved fortuitous in the long-run for Notre Dame. The 1913 schedule was one of the most difficult Notre Dame had seen to that point with six of seven opponents Notre Dame had never faced before.

Back Row: Assistant Coach Edwards, Emmett Keefe, Ray Eichenlaub, Albert King, Freeman (Fitz) Fitzgerald, Charles (Sam) Finegan, Coach Jesse Harper

Middle Row: Ralph (Zipper) Lathrop, Keith (Deak) Jones, Joe Pliska, Captain Knute Rockne, Gus Dorais, Fred (Gus) Gushurst, Al Feeney

Front Row: Allen (Mal) Elward, Alfred (Dutch) Bergman, Bill Cook, Art (Bunny) Larkin

The 1913 Notre Dame squad was chock-full of veterans and the students were all hopeful for another successful season; however, Scholastic complained “we know Mid-West critics too well to hope for the Western Championship this year” [Scholastic, 10/25/1913, page 80]. The Montgomery [Alabama] Adviser noted that Notre Dame’s “[p]resent prospects point to one of the strongest elevens the university [Notre Dame] had ever had” [“Twenty-Two Candidates Out at Notre Dame,” The Montgomery Adviser, 09/20/1913].

Notre Dame had an easy time with the home opener against Ohio Northern, the only previously-played team on the schedule, winning 87-0 while Knute Rockne sustained an early rib injury. South Dakota was next and proved a bit more of a struggle, even though the scored ended up 20-7 with some late Notre Dame scores. Alma rounded out the end of the home stretch with Notre Dame defeating them soundly 62-0.

[photoshelter-img i_id=”I0000RxoaICemHGw” buy=”1″ caption=”Football Game Scene – Notre Dame vs. Ohio Northern, 1913/1004. Captain Knute Rockne leading the team onto Cartier Field before the first game of the season.” width=”576″ height=”469″]

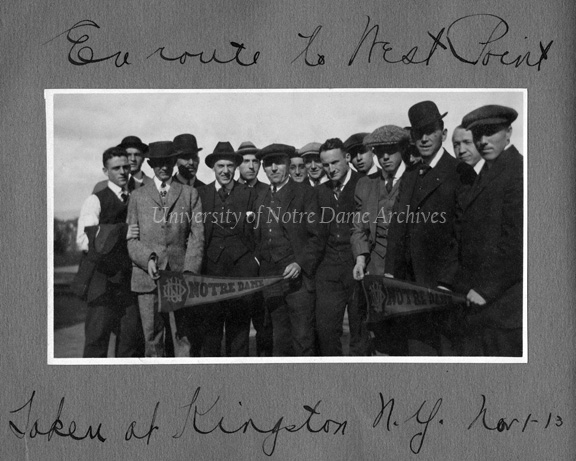

The last four games were on the road, taking the Notre Dame squad to far-flung corners of the country for the first time. The road trip started with the famous game versus Army at West Point on November 1, 1913. Army was a big dog in the Eastern Conference, so it was a big deal to get on their schedule. Fortunately, Army had a few dates open on their schedule and they were accommodating to Notre Dame. When Jesse Harper was making the schedule for the 1913 season, he actually wrote to Yale a few days before Army. Unfortunately, there is no reply in the files, so we don’t know if there was a scheduling conflict or a lack of interest as to why Notre Dame didn’t play them in 1913 but did in 1914.

Part of the legend is true – the forward pass was crucial to Notre Dame’s victory, as the Army team outweighed many of the Notre Dame players. Notre Dame didn’t invent the forward pass, but they brought a balanced offense of running and passing played with such precision and speed as had never before been seen in a major collegiate game. The mix of offensive plays weakened and confused the Army defense. The plays weren’t formulated overnight and it wasn’t a secret, as Notre Dame had used such game strategy previously throughout the season. The Dallas Morning News even predicted that Notre Dame could edge out Army with use of the forward pass balanced with Ray Eichenlaub’s running game, which was thoroughly tested out in the Alma game [Dallas Morning News, 10/30/1913].

Quarterback Charles (Gus) Dorais had perfected the timing of routes with his open receivers Knute Rockne, Joe Pliska, and Charles (Sam) Finegan so that the plays ran like a well-oiled machine. Dorais was never under pressure and he constantly switched things up, never throwing to the same receiver twice in a row. Dorais completed 13 of 17 passes for 243 yards and three of the five touchdowns in the air to defeat Army 35-13.

Notre Dame proved that the forward pass could be an effective weapon in an offensive arsenal and that it wasn’t just a trick play or a last-ditch option, as it had mostly been seen in the past. The defeat of Army in 1913 gave more legitimacy to the open Western-style of playing versus the traditional, smashmouth football of the East. If done right, the passing game allowed for more scoring in a quicker amount of time and it was safer for the players. In regards to the Army game, the New York Times noted that “[f]ootball men marveled at this startling display of open football. Bill Roper, former head coach at Princeton, who was one of the officials of the game, said that he had always believed that such playing was possible under the new rules, but that he had never seen the forward pass developed to such a state of perfection” [reprinted in Scholastic, 11/08/1913, page 107].

Notre Dame then traveled to Penn State and handed them their first defeat on home soil 14-7. A few weeks later, Notre Dame defeated Christian Brothers College in Saint Louis 20-7, and then headed to Texas for a Thanksgiving Day game. Notre Dame was the first school north of the Mason-Dixon line to play Texas. Notre Dame took advantage of their time in Austin to practice at Saint Edward’s University, an institution also founded by Rev. Edward Sorin and run by the Congregation of the Holy Cross. The extra practice paid off as Notre Dame secured a 30-7 victory.

After Notre Dame’s second undefeated, untied season in as many years, many schools tried to plan a post-season game with Notre Dame, including Louisiana State University, Michigan State, Oklahoma, and Seattle A.C. Timing, extra training, and extraneous travel were obstacles to scheduling more games in 1913, so nothing materialized at the time, but it probably did give Jesse Harper leverage when it came to negotiating future schedules.

While already on the college football map before 1913, Notre Dame athletics was becoming better known as a household name outside of the Midwest. Notre Dame’s student population, and thus alumni, have always been geographically diverse, so rooters met them along the way. Notre Dame had an entire bleacher section filled with fans and alumni at West Point. The extensive road trips starting in 1913 coupled with the pervasive anti-Catholicism in America helped Notre Dame to begin building her “subway alumni.” Jesse Harper saw that he could build a fan base, and thus revenue, by having competitive athletic schedules. His vision of excellence was the foundation upon which Knute Rockne continued to build when he became Coach and Athletic Director, securing Notre Dame’s place at the top of collegiate football history.

Sources:

Scholastic

PATH 1913 Football Season

Shake Down the Thunder: The Creation of Notre Dame Football by Murray Superber

Forward Pass by Philip Brooks

Notre Dame Scrapbook c1910-1913 [GSBC]

Notre Dame Football Scrapbook 1913 [GSBH]

GCLE 1/03