Summarizing the state of the Catholic Youth Literature Project

Posted on March 30, 2012 in Uncategorized by Eric Lease Morgan

This posting summarizes the purpose, process, and technical infrastructure behind the Catholic Youth Literature Project. In a few sentences, the purpose was two-fold: 1) to enable students to learn what it meant to be Catholic during the 19th century, and 2) to teach students the value of reading “closely” as well as from a “distance”. The process of implementing the Project required the time and skills of a diverse set of individuals. The technical infrastructure is built on a large set of open source software, and the interface is far from perfect.

Purpose

The purpose of the project was two-fold: 1) to enable students to learn what it meant to be Catholic during the 19th century, and 2) to teach students the value of reading “closely” as well as from a “distance”. To accomplish this goal a faculty member here at the University of Notre Dame (Sean O’Brien) sought to amass a corpus of materials written for Catholic youth during the 19th century. This corpus was expected to be accessible via tablet-based devices and provide a means for “reading” the texts in the traditional manner as well as through various text mining interfaces.

During the Spring Semester students in a survey class were lent Android-based tablet computers. For a few weeks of the semester these same students were expected to select one or two texts from the amassed corpus for study. Specifically, they were expected to read the texts in the traditional manner (but on the tablet computer), and they were expected to “read” the texts through a set of text mining interfaces. In the end the the students were to outline three things: 1) what did you learn by reading the text in the traditional way, 2) what did you learn by reading the text through text mining, and 3) what did you learn by using both interfaces at once and at the same time.

Alas, the Spring semester has yet to be completed, and consequently what the students learned has yet to be determined.

Process

The process of implementing the Project required the time and skills of a diverse set of individuals. These individuals included the instructor (Sean O’Brien), two collection development librarians (Aedin Clements and Jean McManus), and librarian who could write computer programs (myself, Eric Lease Morgan).

As outlined above, O’Brien outlined the overall scope of the Project.

Clements and McManus provided the means of amassing the Project’s corpus. A couple of bibliographies of Catholic youth literature were identified. Searches were done against the University of Notre Dame’s library catalog. O’Brien suggested a few titles. From these lists items were selected for inclusion for purchase, from the University library’s collection, as well as from the Internet Archive. The items for purchase were acquired. The items from the local collection were retrieved. And both sets of these items were sent off for digitization and optical character recognition. The results of the digitization process were then saved on a local Web server. At the same time, the items identified from the Internet Archive were mirrored locally and saved in the same Web space. About one hundred items items were selected in all, and they can be seen as a set of PDF files. This process took about two months to complete.

Technical infrastructure

The Project’s technical infrastructure enables “close” and “distant” reading, but the interface is far from perfect.

From the reader’s (I don’t use the word “user” anymore) point of view, the Project is implemented through a set of Web pages. Behind the scenes, the Project is implemented with an almost dizzying array of free and open source software. The most significant processes implementing the Project are listed and briefly described below:

- mirroring – Much of the text mining services require extensive analysis of the original item. To accomplish this local copies of the texts were mirrored locally. By feeding the venerable wget program with a list of URLs based on Internet Archive unique identifiers, mirroring content locally is trivial.

- name-entity extraction – There was a desire to list the underlying names, places, and organizations from each text. These things can put a text into a context for the reader. Are there a lot of Irish names? Is there a preponderance of place names from the United States? To accomplish this task and assist in answering these sorts of questions, a Perl script was written around the Stanford Named Entity Recognizer. This script (txt2ner.pl) extracts the entities, looks them up in DBedia, and saves metadata (abstracts, URLs to images, as well as latitudes & longitudes) describing the entities to a locally defined XML file for later processing. (See an example.) A CGI script (ner.cgi) was then written to provide a reader-interface to these files.

- parts-of-speech extraction – Just as lists of named entities can be enlightening so can lists of a text’s parts-of-speech. Are the pronouns generally speaking masculine or feminine? Over all, are the verbs active or passive? To what degree are color words used words in the text? To begin to answer these sorts of questions, a Perl script exploited a Perl module called Lingua::TreeTagger. The script (pos-tag.pl) extracts parts-of-speech from a text file and saves the result as a simple tab-delimited file for later use. (See an example.)

- word/phrase tabulation and concordancing – To support rudimentary word and phrase tabulations, as well as a concordance interface, an Apache module (Concordance.pm) was written around two more Perl modules. The first, Lingua::EN::Ngram, extracts word and phrase occurrences. The second, Lingua::Concordance, provides an object-oriented keyword-in-context interface.

- metadata enhancement and storage – A rudimentary catalog listing the items in the Project’s corpus was implemented using a Perl module called MyLibrary. The MARC records describing each item in the corpus were first parsed. Desired metadata elements were mapped to MyLibrary fields, facets, and terms. Each item in the corpus was then analyzed in terms of word length as well as readability score through the use of yet another Perl module called Lingua::EN::Fathom. These additional metadata elements were then added to the underlying “catalog”. To accomplish this set of tasks two additional Perl scripts were written (add-author-title.pl and add-size-readability.pl).

- HTML creation – A final Perl script was written to bring all the parts together. By looping through the “catalog” this script (make-catalog.pl) generates HTML files designed for display on tablet devices. These HTML files make heavy use of JQuery Mobile, and since no graphic designer was a part of the Project, JQuery Mobile was a godsend.

The result — the Catholic Youth Literature Project — is a system that enables the reader to view the texts online as well as do some analysis against them. The system functions in that it does not output invalid data, and it does provide enhanced access to the texts.

The home page is simply a list of covers and associated titles.

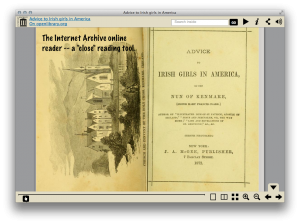

The Internet Archive online reader is one option for “close” reading.

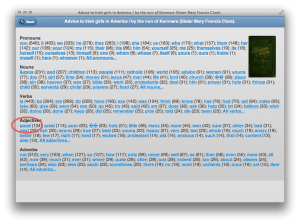

The list of parts-of-speech provides the reader with some context. Notice how the word “good” is the most frequently used adjective.

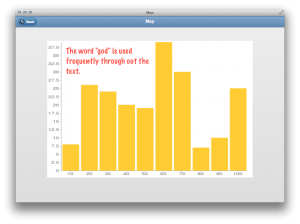

The histogram feature of the concordance allows the reader to see where selected words appear in the text. For example, in this text the word “god” is used rather consistently.

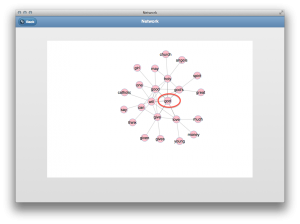

A network diagram allows the reader to see what words are used “in the same breath” as a given word. Here the word “god” is frequently used in conjunction with “good”, “holy”, “give”, and “love”.

Summary

To summarize, the Catholic Youth Literature Project is far from complete. For example, it has yet to be determined whether or not the implementation has enabled students to accomplish the Project’s stated goals. Does it really enhance the use and understanding of a text? Second, the process of selecting, acquiring, digitizing, and integrating the texts into the library’s collection is not streamlined. Finally, usability of the implementation is still in question. On the other hand, the implementation is more than a prototype and does exemplify how the process of reading is evolving over time.