ORCID Outreach Meeting (May 21 & 22, 2014)

Posted on June 13, 2014 in Uncategorized

This posting documents some of my experiences at the ORCID Outreach Meeting in Chicago (May 21 & 22, 2014).

This posting documents some of my experiences at the ORCID Outreach Meeting in Chicago (May 21 & 22, 2014).

As you may or may now know, ORCID is an acronym for “Open Researcher and Contributor ID”.* It is also the name of a non-profit organization whose purpose is to facilitate the creation and maintenance of identifiers for scholars, researchers, and academics. From ORCID’s mission statement:

ORCID aims to solve the name ambiguity problem in research and scholarly communications by creating a central registry of unique identifiers for individual researchers and an open and transparent linking mechanism between ORCID and other current researcher ID schemes. These identifiers, and the relationships among them, can be linked to the researcher’s output to enhance the scientific discovery process and to improve the efficiency of research funding and collaboration within the research community.

A few weeks ago the ORCID folks facilitated a user’s group meeting. It was attended by approximately 125 people (mostly librarians or people who work in/around libraries), and some of the attendees came from as far away as Japan. The purpose of the meeting was to build community and provide an opportunity to share experiences.

The meeting itself was divided into number of panel discussions and a “codefest”. The panel discussions described successes (and failures) for creating, maintaining, enhancing, and integrating ORCID identifiers into workflows, institutional repositories, grant application processes, and information systems. Presenters described poster sessions, marketing materials, information sessions, computerized systems, policies, and politics all surrounding the implementation of ORCID identifiers. Quite frankly, nobody seemed to have a hugely successful story to tell because too few researchers seem to think there is a need for identifiers. I, as a librarian and information professional, understand the problem (as well as the solution), but outside the profession there may not seem to be much of a problem to be solved.

That said, the primary purpose of my attendance was to participate in the codefest. There were less than a dozen of us coders, and we all wanted to use the various ORCID APIs to create new and useful applications. I was most interested in the possibilities of exploiting the RDF output obtainable through content negotiation against an ORCID identifier, a la the command line application called curl:

curl -L -H "Accept: application/rdf+xml" http://orcid.org/0000-0002-9952-7800

Unfortunately, the RDF output only included the merest of FOAF-based information, and I was interested in bibliographic citations.

Consequently I shifted gears, took advantage of the ORCID-specific API, and I decided to do some text mining. Specifically, I wrote a Perl program — orcid.pl — that takes an ORCID identifier as input (ie. 0000-0002-9952-7800) and then:

- queries ORCID for all the works associated with the identifier**

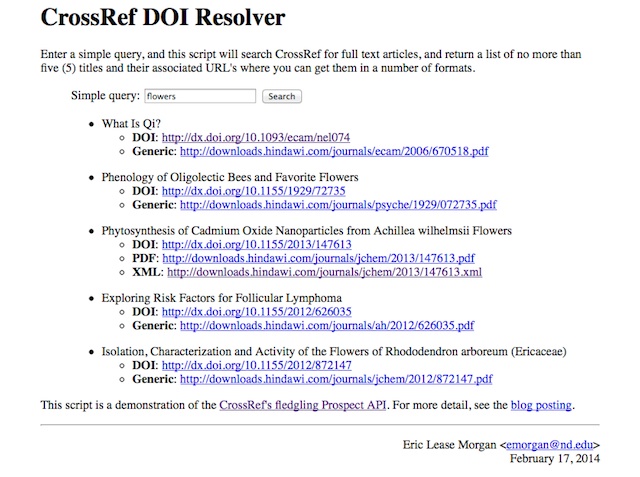

- extracts the DOIs from the resulting XML

- feeds the DOIs to a program called Tika for the purposes of extracting the full text from documents

- concatenates the result into a single stream of text, and sends the whole thing to standard output

For example, the following command will create a “bag of words” containing the content of all the writings associated with my ORCID identifier and have DOIs:

$ ./orcid.pl 0000-0002-9952-7800 > morgan.txt

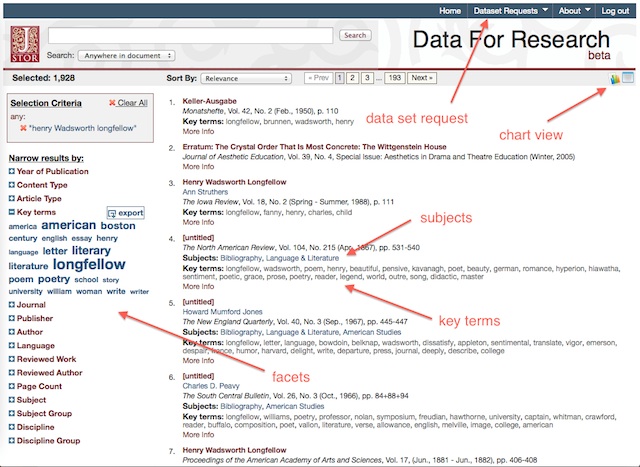

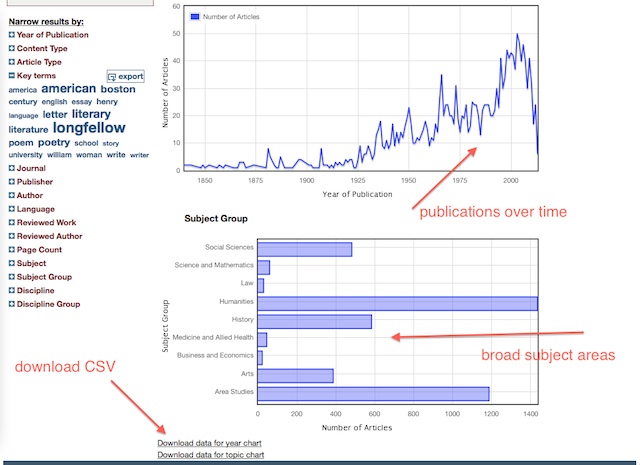

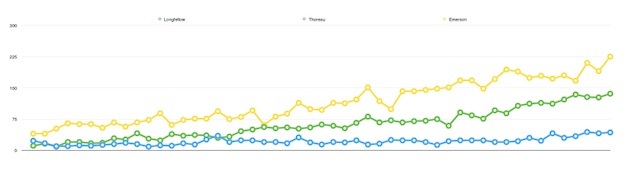

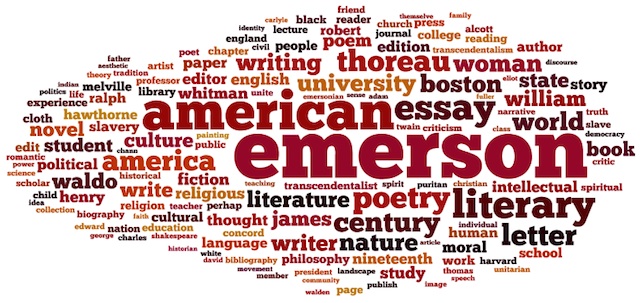

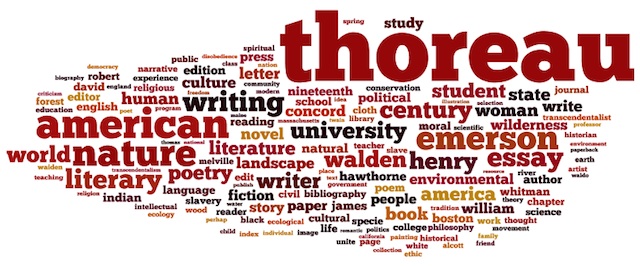

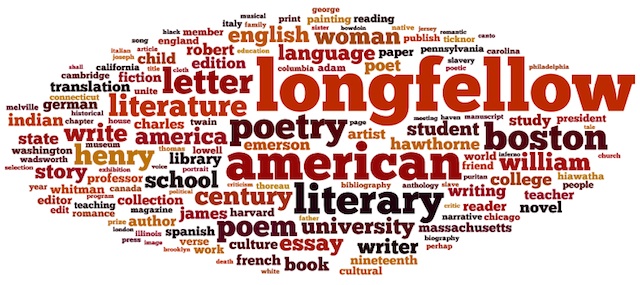

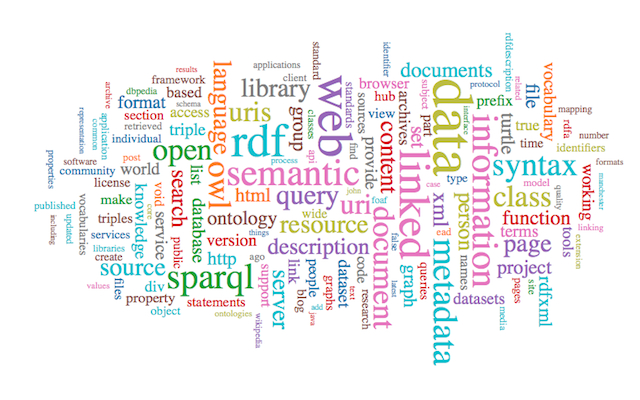

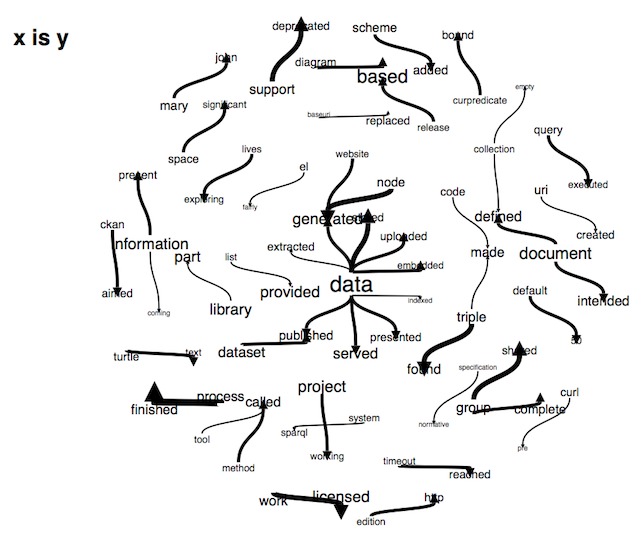

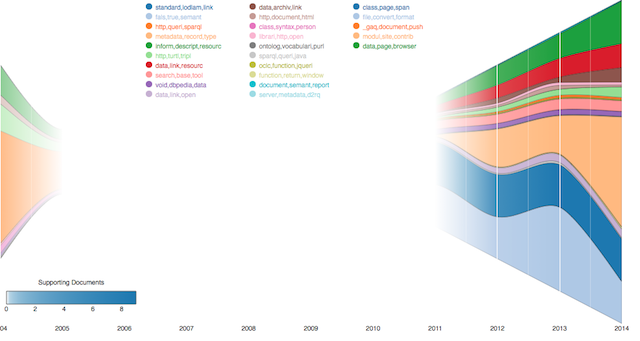

Using this program I proceeded to create a corpus of files based on the ORCID identifiers of eleven Outreach Meeting attendees. I then used my “tiny text mining tools” to do analysis against the corpus. The results were somewhat surprising:

- The most significant key words shared across the corpus of eleven people included: information, system, site, and orcid.

- The authors Haak and Paglione wrote the most similar articles. (They both wrote about ORCID.) Morgan and Havert were a very close second. (We both wrote about “information” and “sites”.)

- The DOIs often point to splash pages, and consequently my “bags of words” included lots of content about cookies and publishers as opposed to meaty journal article content. ***

Ideally, the hack I wrote would allow a person to feed one or more identifiers to a system and output a report summarizing and analyzing the journal article content at a glance — a quick & easy “distant reading” tool.

I finished my “hack” in one sitting which gave me time to attend the presentations of the second day.

All of the hacks were added to a pile and judged by a vendor on their utility. I’m proud to say that Jeremy Friesen’s — a colleague here at Notre Dame — hack won a prize. His application followed the links to people’s publications, created a screen dump of the publications’ root pages, and made a montage of the result. It was a visual version of orcid.pl. Congratulations, Jeremy!

I’m very glad I attended the Meeting. I reconnected with a number of professional colleagues, and I my awareness of researcher identifiers was increased. More specifically, there seem to be a growing number of these identifiers. Examples for myself include:

- ISNI – http://isni.org/isni/0000000035290715

- LC – http://id.loc.gov/authorities/names/n94036700

- ORCID – http://orcid.org/0000-0002-9952-7800

- ResearcherID – http://www.researcherid.com/rid/F-2062-2014

- Scopus – http://www.scopus.com/authid/detail.url?authorId=25944695600

- VIAF – http://viaf.org/viaf/26290254

And for a really geeky good time, I learned to create the following set of RDF triples with the use of these identifiers:

@prefix dc: <http://purl.org/dc/elements/1.1/> . <http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/07378831211213201> dc:creator "http://isni.org/isni/0000000035290715" , "http://id.loc.gov/authorities/names/n94036700" , "http://orcid.org/0000-0002-9952-7800" , "http://viaf.org/viaf/26290254" , "http://www.researcherid.com/rid/F-2062-2014" , "http://www.scopus.com/authid/detail.url?authorId=25944695600" .

I learned about the (subtle) difference between an identifier and a authority control record. I learned of the advantages and disadvantages the various identifiers. And through a number of serendipitous email exchanges, I learned about ISNIs which are a NISO standard for identifiers and seemingly popular in Europe but relatively unknown here in the United States. For more detail, see the short discussion of these things in the Code4Lib mailing list archives.

Now might be a good time for some of my own grassroots efforts to promote the use of ORCID identifiers.

* Thanks, Pam Masamitsu!

** For a good time, try http://pub.orcid.org/0000-0002-9952-7800/orcid-works, or substitute your identifier to see a list of your publications.

*** The problem with splash screens is exactly what the very recent CrossRef Text And Data Mining API is designed to address.

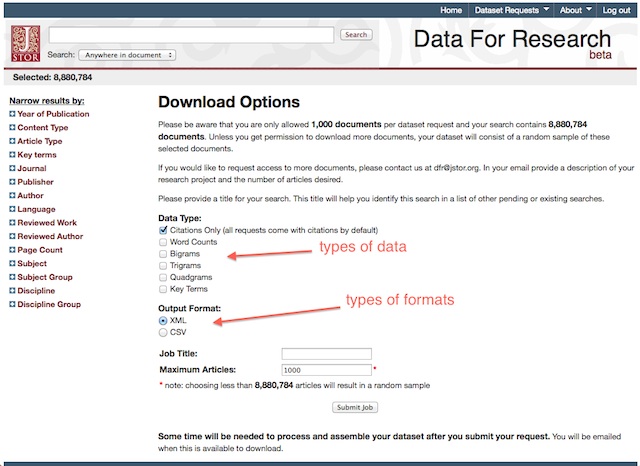

A few weeks ago I learned that CrossRef’s Text And Data Mining (TDM) API had gone version 1.0, and this blog posting describes my tertiary experience with it.

A few weeks ago I learned that CrossRef’s Text And Data Mining (TDM) API had gone version 1.0, and this blog posting describes my tertiary experience with it.

This posting describes how to turn off and on a thing called the jobs topic in the Code4Lib mailing list.

This posting describes how to turn off and on a thing called the jobs topic in the Code4Lib mailing list.

A couple of weeks ago Kevin Phaup took the lead of facilitating a 3D printing workshop here in the Libraries’s Center For Digital Scholarship. More than a dozen students from across the University participated. Kevin presented them with an overview of 3D printing, pointed them towards a online 3D image editing application (

A couple of weeks ago Kevin Phaup took the lead of facilitating a 3D printing workshop here in the Libraries’s Center For Digital Scholarship. More than a dozen students from across the University participated. Kevin presented them with an overview of 3D printing, pointed them towards a online 3D image editing application (