by Julia Douthwaite, Professor of French, University of Notre Dame

This summer I am spending my days in the Department of Special Collections at Notre Dame’s library, systematically making my way through 60-some of the most controversial-sounding titles of French books published during the French Revolution (of the 266 total). I am looking for clues about who read these books, what they liked, and when, as based on underlinings, marginalia, and any clues I can find on provenance; it is also interesting to learn about historical facets of book binding and illustration. The closest thing to being in a European library is being in a Rare Books room in the USA.

I am doing so in anticipation of the colloquium, Collecting the French Revolution, in Greoble and Vizille France, 23-25 September 2015. It will be fun to show how the collection of such materials ended up here, in the hinterlands of north-central Indiana!

So far, I have found some intriguing books. Two are interesting because of their ties to the university’s history: a 1794 book of revolutionary legislation is stamped “Treasure Room”–the former name of Special Collections–and a history of the Church dated 1791 is a living testimony to the ravages of fire and water damage which swept through the library in 1879. It was saved from the fire by a student, from whom it was returned years later.

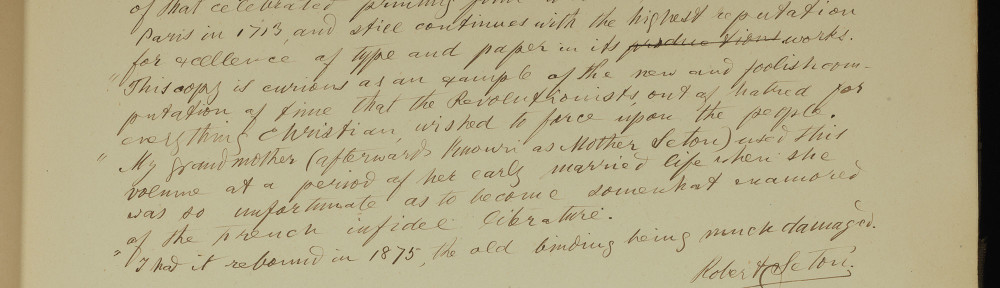

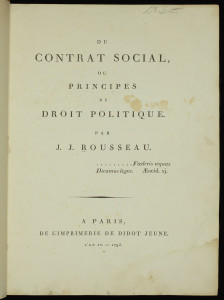

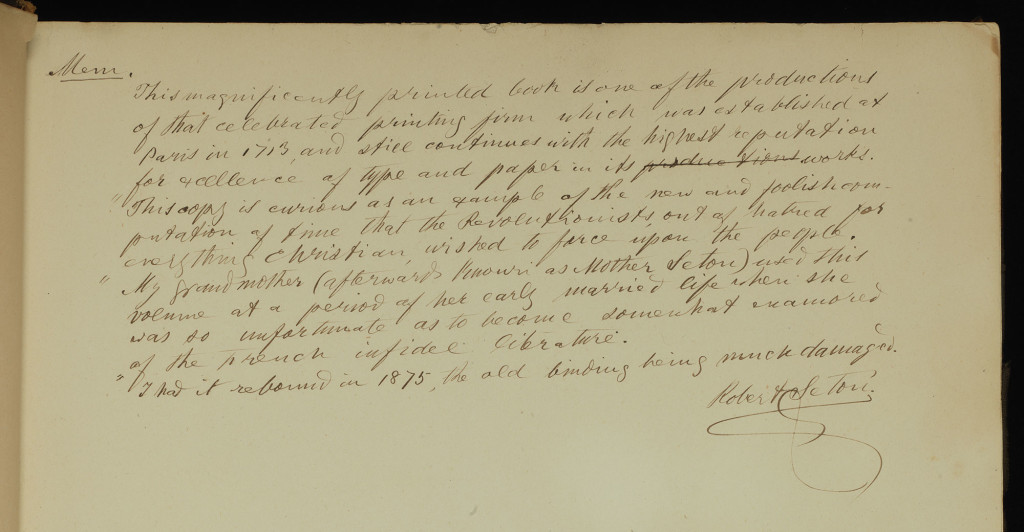

The most intellectually vibrant example of marginalia has to be the 1795 copy of Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s incendiary work of political theory, Du Contrat social–which contains notions such as general will and popular sovereignty–once owned by a certain Elizabeth Ann Seton. Inside the front cover one finds this inscription: “This copy is curious as an example of the new and foolish computation of time that the Revolutionists, out of hatred for everything Christian, wished to force upon the people. My grandmother (afterwards known as Mother Seton) used this volume at a period of her early married life when she was so unfortunate as to become somewhat enamored of the French infidel literature.” It is signed Robert Seton (a monsignor in the Roman Catholic Church and titular archbishop of Heliopolis, who donated it to Notre Dame). Better than any work by the philosopher Theodor Adorno or the intellectual historian Jonathan Israel, this one book holds within it a cautionary tale on the dialectics of modern thought, and the errors of Enlightenment philosophy , considered as a cause of the French Revolution. It also shines some light on the evolution in Mother Seton’s thinking from a youthful age; she would have been 21 years old in 1795, living the life of a wealthy New Yorker after marrying a successful merchant in the import trade two years earlier. Perhaps he imported new ideas along with the other stock from Europe!

The closest connection between Indiana and the French Revolution has to be the memoirs of Simon Bruté, born in Rennes in 1779, died in Vincennes, IN, in 1839 after serving as the first bishop of Vincennes. Its subtitle promises: “sketches describing his recollections of scenes connected with the French revolution.” I was initially wondering if the anti-revolutionary views of the clergy would be reflected in the collection and they are. But there are also an abundance of sources representing other political views. Along with several works by the infamous conspiracy theorist Abbé Barruel, there is a gorgeous edition of the Enlightenment’s most radical work of information sharing—the first Wikipedia one might say—L’Encyclopédie (the entire 17 volume set, dated 1765, with the supplement and the plates from later editions). Some say that L’Encyclopédie did more to promote a revolutionary consciousness than any other book of the time, by making trade secrets on industrial processes and artisanal practices accessible to all. This makes Notre Dame a great teaching library: students have a rich archive to explore in the search of learning how people thought long ago, why revolution broke out in 1789, and what it meant to diverse observers after the fact.

I could write more, but this will doubtless suffice to show you how interesting it can be connect a scholarly interest in revolutionary France with the history of the university and the Holy Cross order.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.