by Rachel Bohlmann, Curator of North Americana and American History Librarian and Erika Hosselkus, Curator of Latin Americana and Strategic Implementation Project Manager

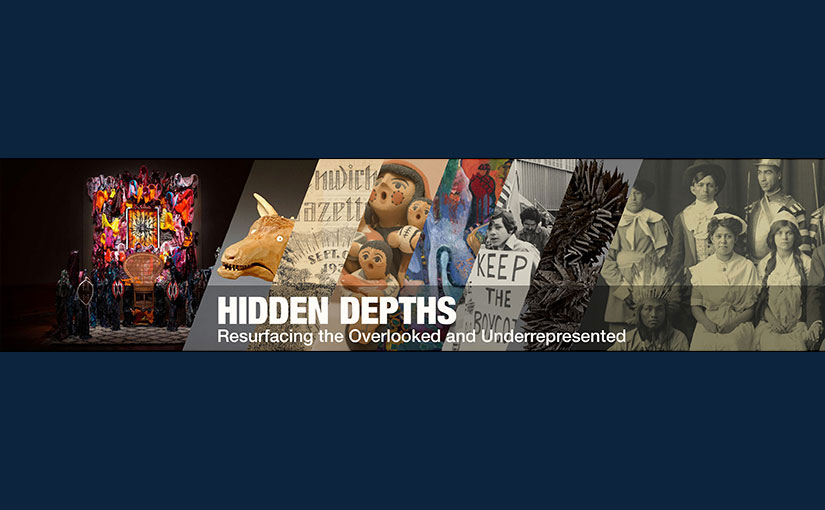

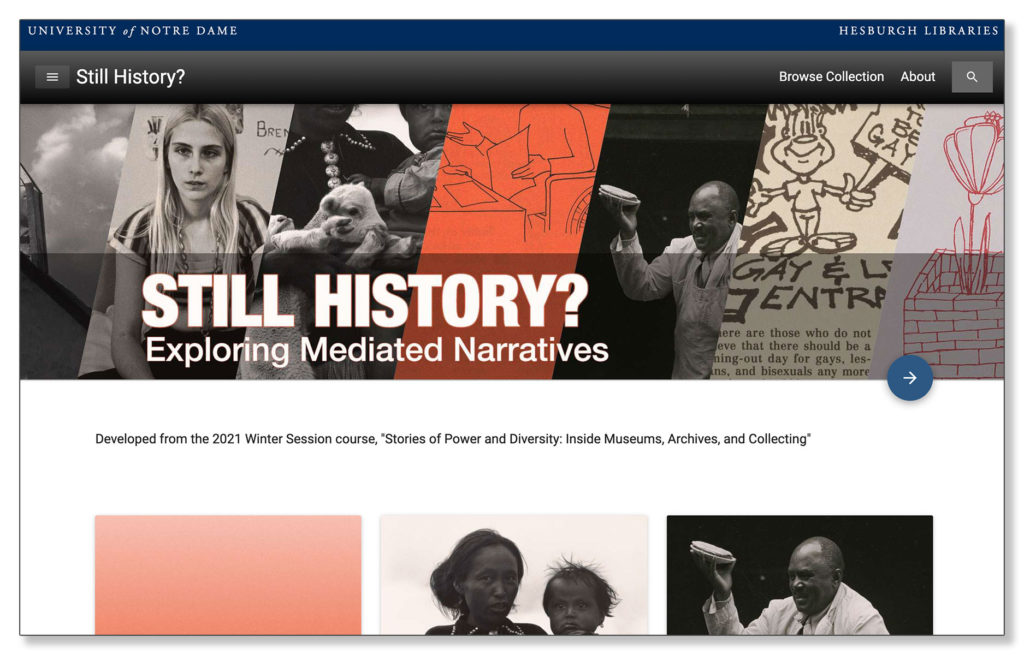

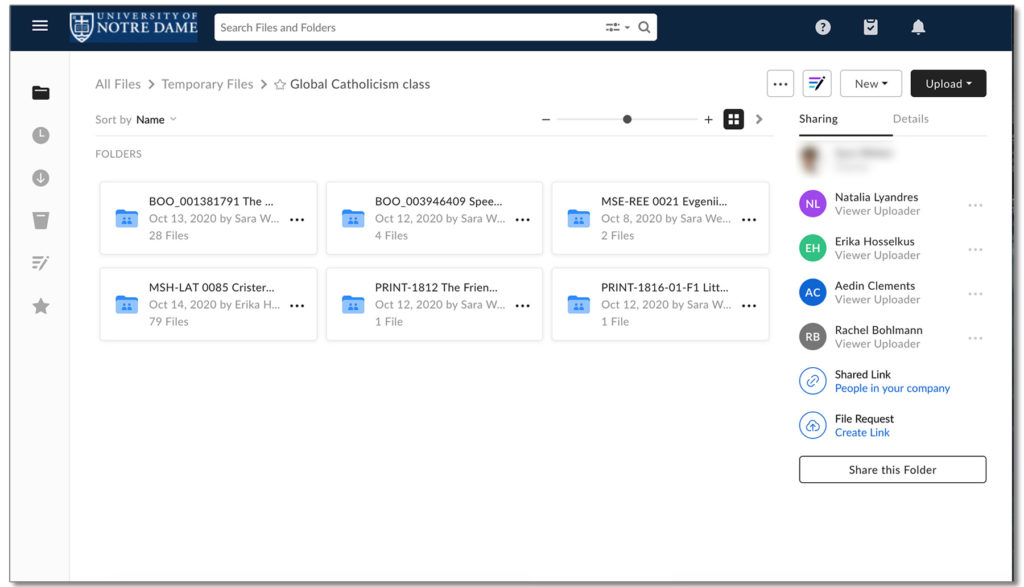

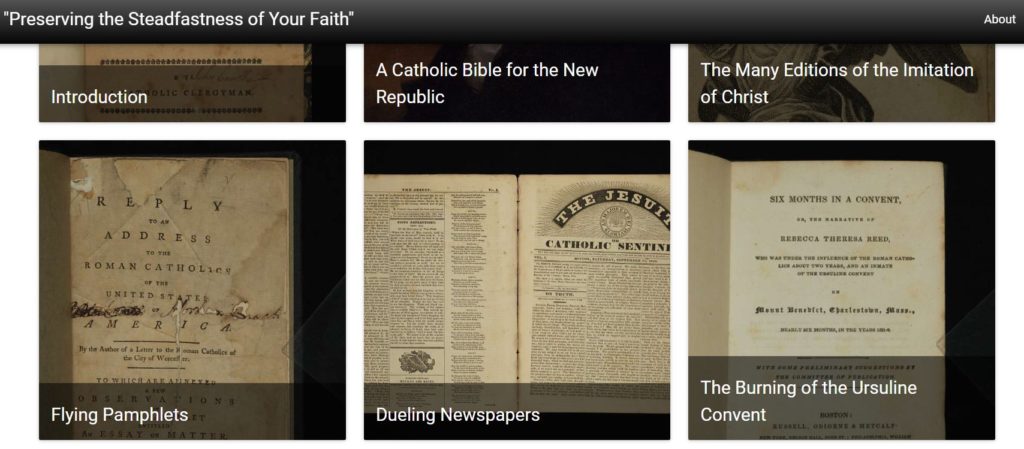

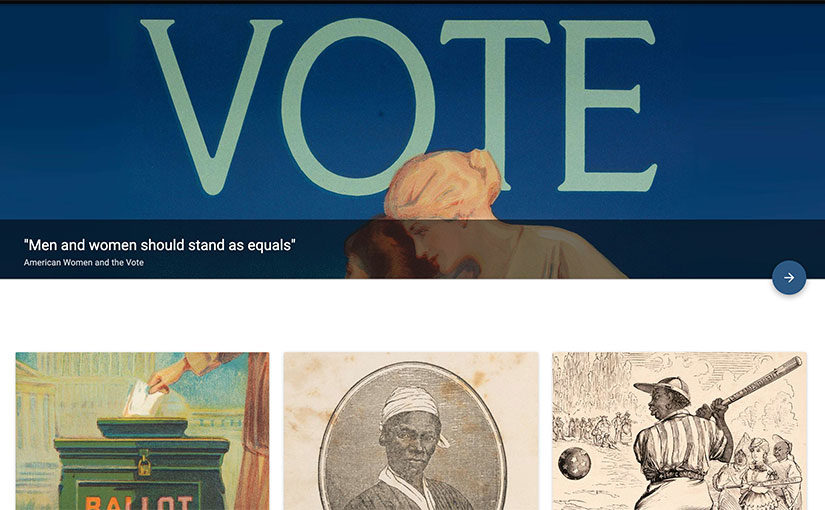

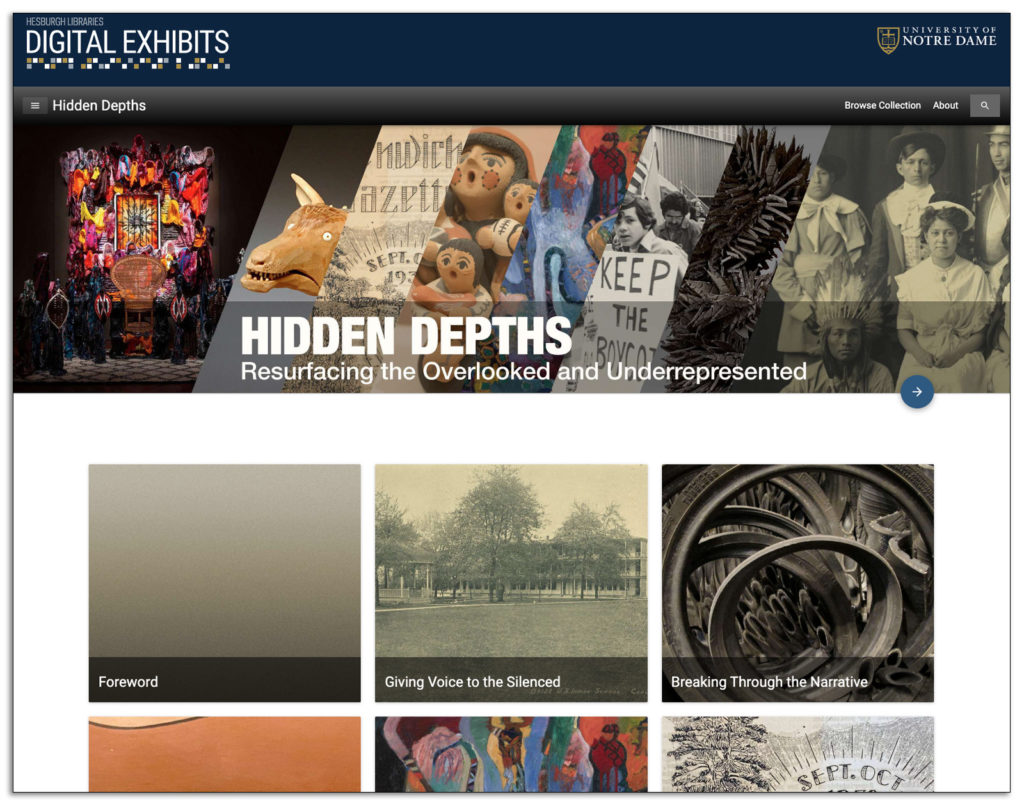

This week Special Collections highlights an online exhibition created by Notre Dame students in their fall 2022 class, Stories of Power and Diversity: Inside Museums, Archives and Collecting. The exhibition, Hidden Depths: Resurfacing the Overlooked and Underrepresented, brings together materials from the University of Notre Dame’s campus repositories–Rare Books and Special Collections, the Snite Museum of Art, and University Archives–selected and interpreted by the students.

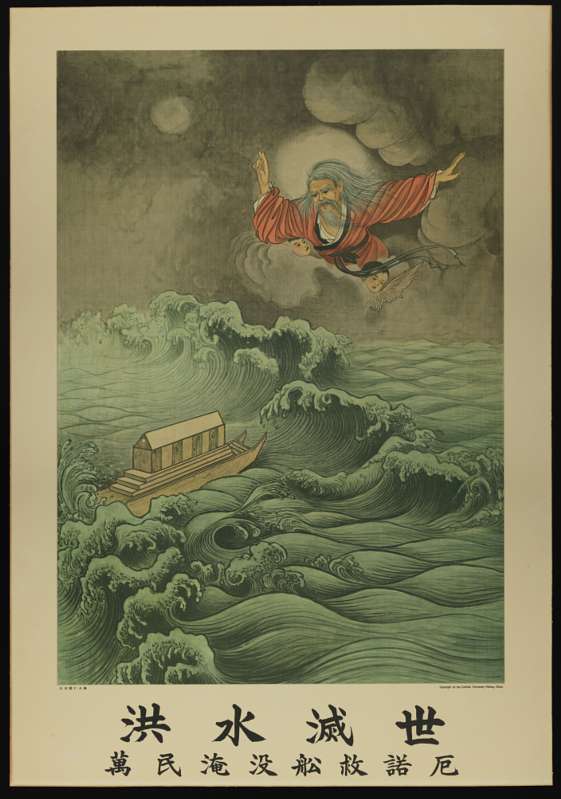

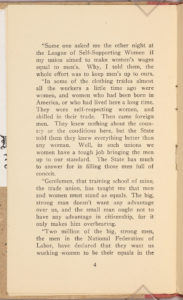

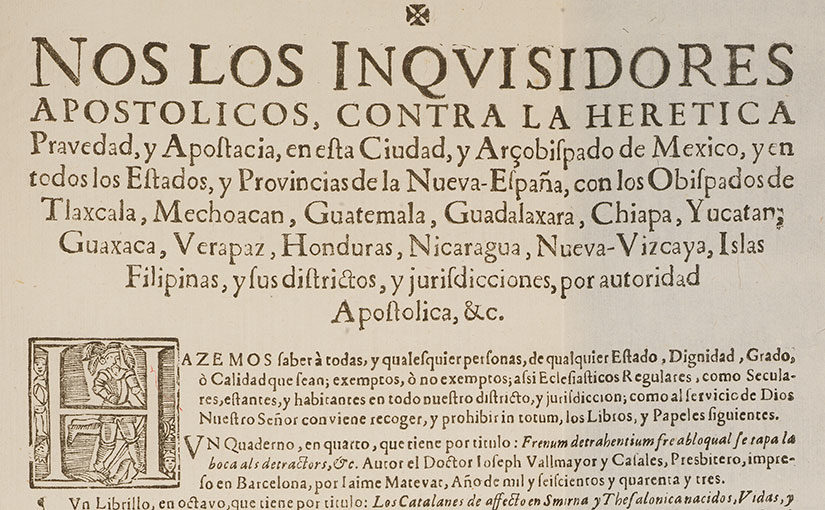

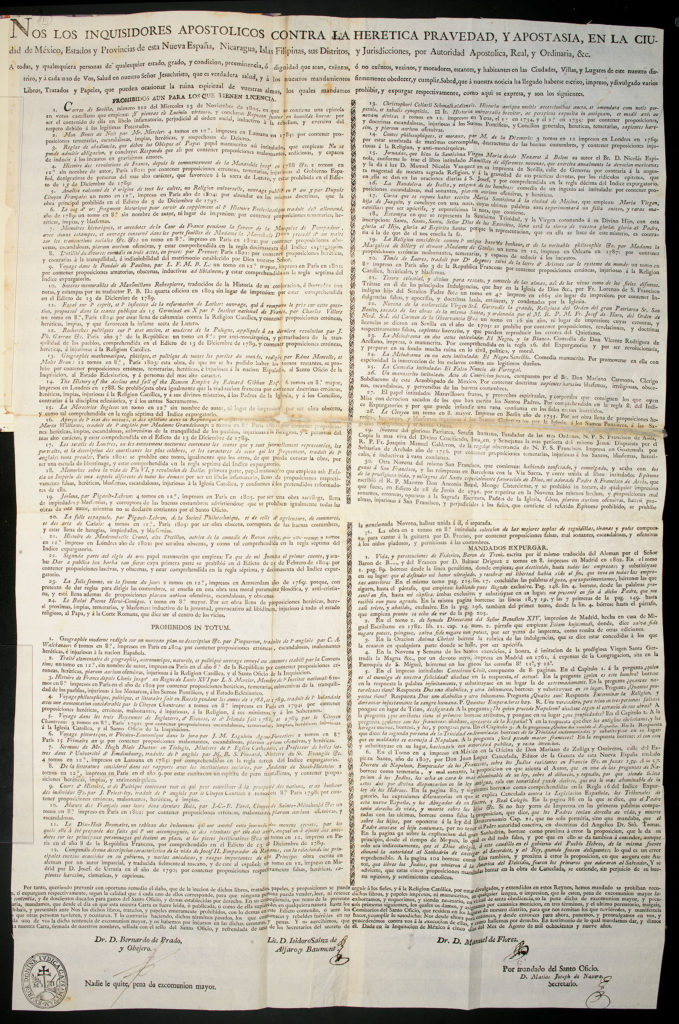

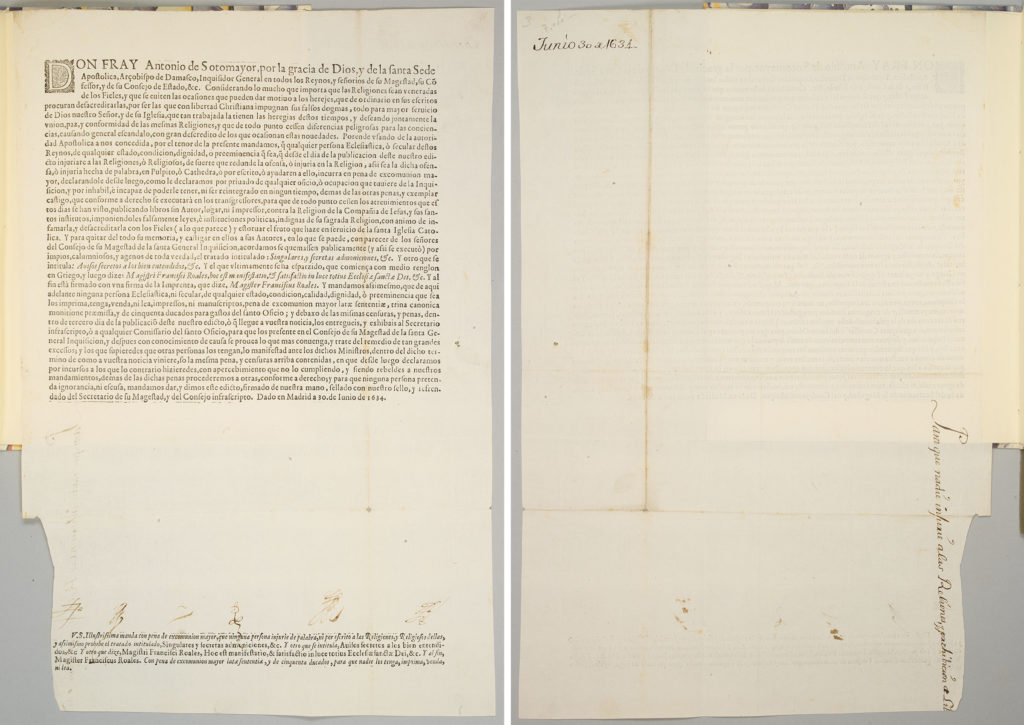

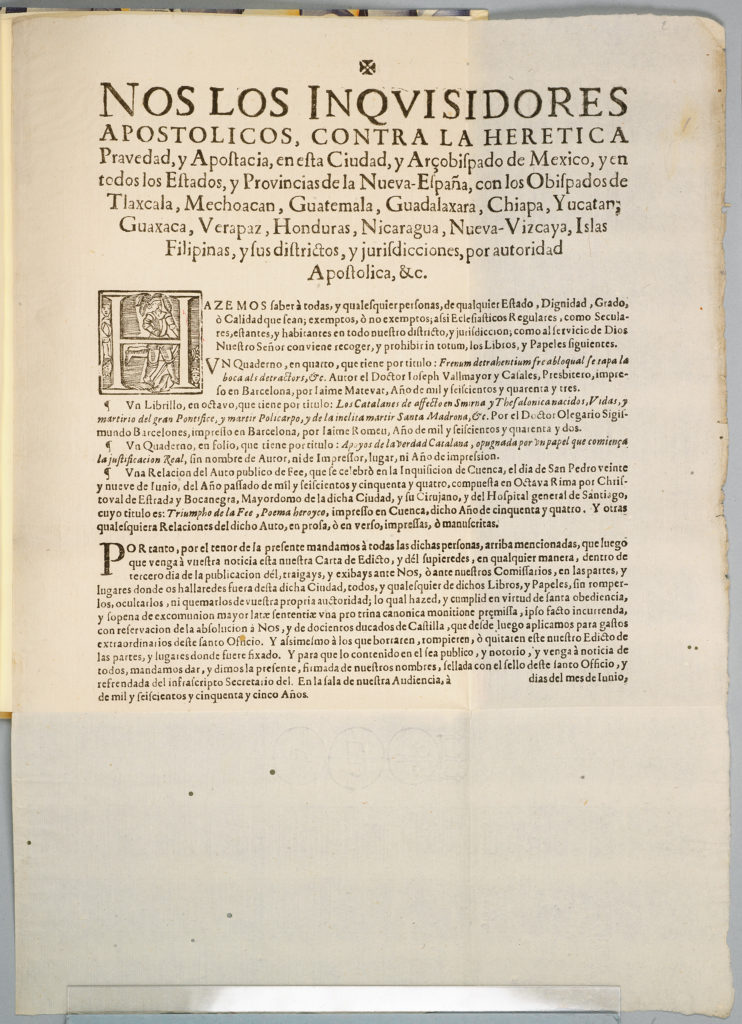

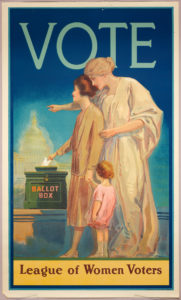

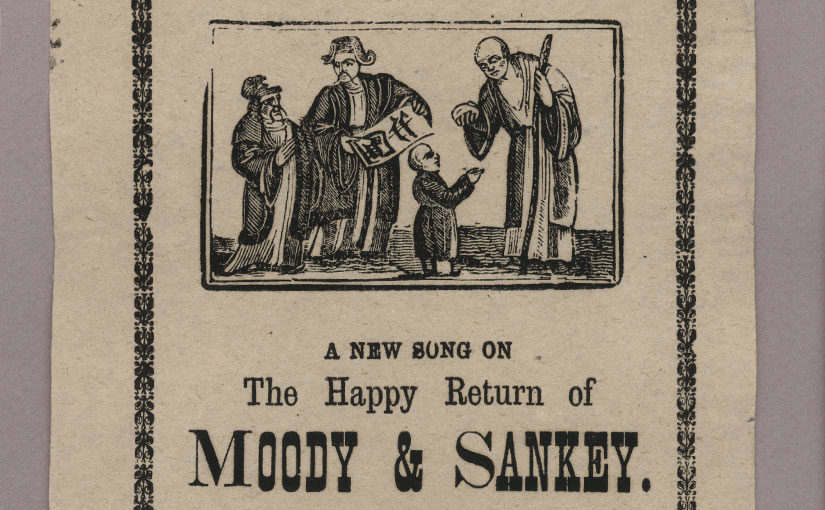

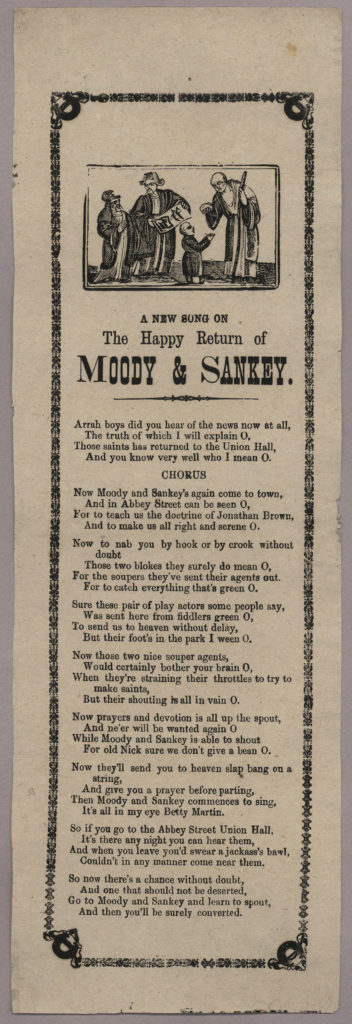

The items displayed here vary in format, time period, medium, style, and content–abstract painting, sculpture, installation art, photographs, and collections of historic documents–and are created by people of diverse backgrounds and experiences. Their selection reflects the themes of the class, which were to explore the history of collecting in Europe and North America and some of the field’s major questions, including, what has been left out? Where are there gaps and silences in collections and archives?

Eight students applied a curatorial gaze to these materials, to examine how they do and do not intersect with themes of diversity. While these curators recognize the diverse identities of the creators of these objects, the showcases comprising this exhibition point viewers to hidden depths. They ask that we consider how identities are nuanced through regional conditions, educational background, economic forces, and personal trauma. And just as importantly, the curators of the show consider how identity and diversity are not always directly linked in one’s art or expression. They also demand that consumers of these pieces of art and historical sources work to apprehend the complexities behind their creation. By extension, they suggest that we take a careful second look in other contexts, beyond the online gallery or the museum.

This exhibition offers interpretation, but it also asks questions, and challenges viewers even as it invites them to connect with holdings in the University of Notre Dame’s campus repositories. Information about the student curators and their experiences in this course can be found in the personal statements at the end of each showcase.

Hidden Depths showcases ways in which students engaged with special collections materials over a semester-long project. The result is a display that uncovers, refocuses and takes an imperative second look.