by David T. Gura, Ph.D., Curator, Ancient and Medieval Manuscripts

During the Middle Ages, the sermon was the most influential vehicle for religious and moral instruction: virtues, vices, canon law, and living the faith all reached the masses in urban centers through preaching. The term ars praedicandi (art of preaching) describes the literary genre of treatises that provide techniques (artes) and instruction for preaching. In addition to the composition of the sermon, artes praedicandi also address how a preacher should comport himself, what to study, and even how to speak and gesture while preaching. Numerous treatises from the twelfth- and thirteenth-century on the topic survive composed by well-known masters like Alan of Lille, Richard of Thetford, Humbert of Romans, and Ranulf Higden, but many anonymous examples exist.

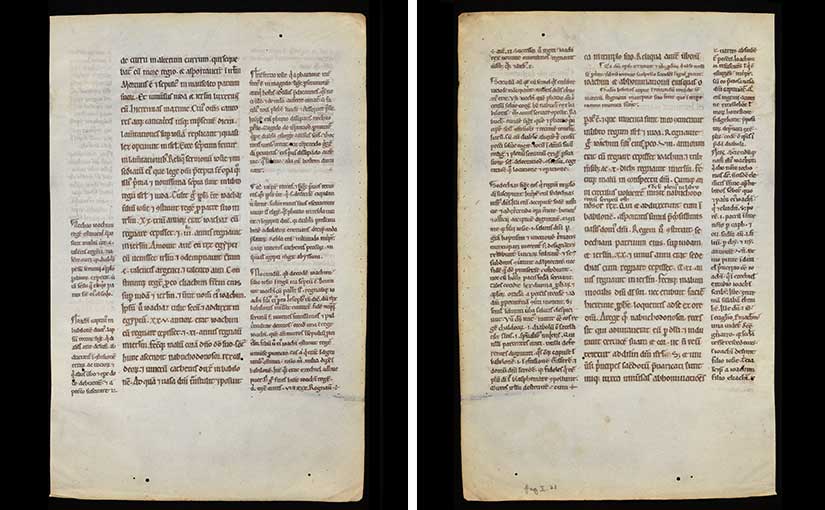

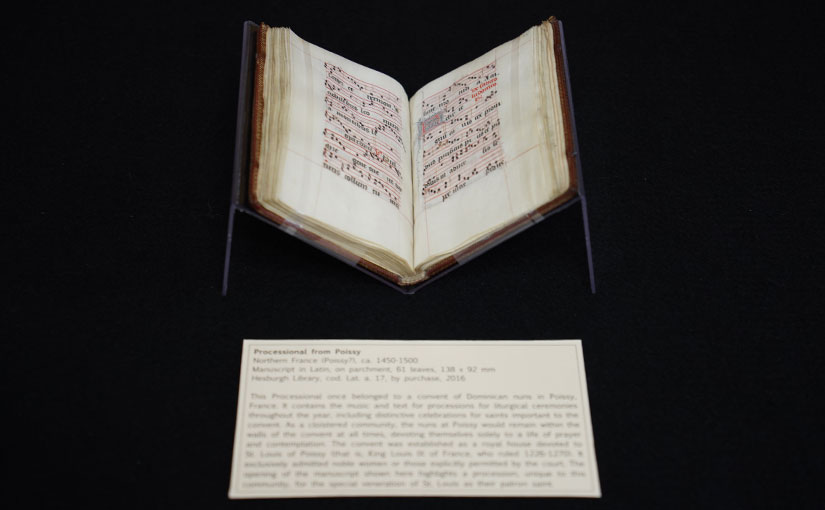

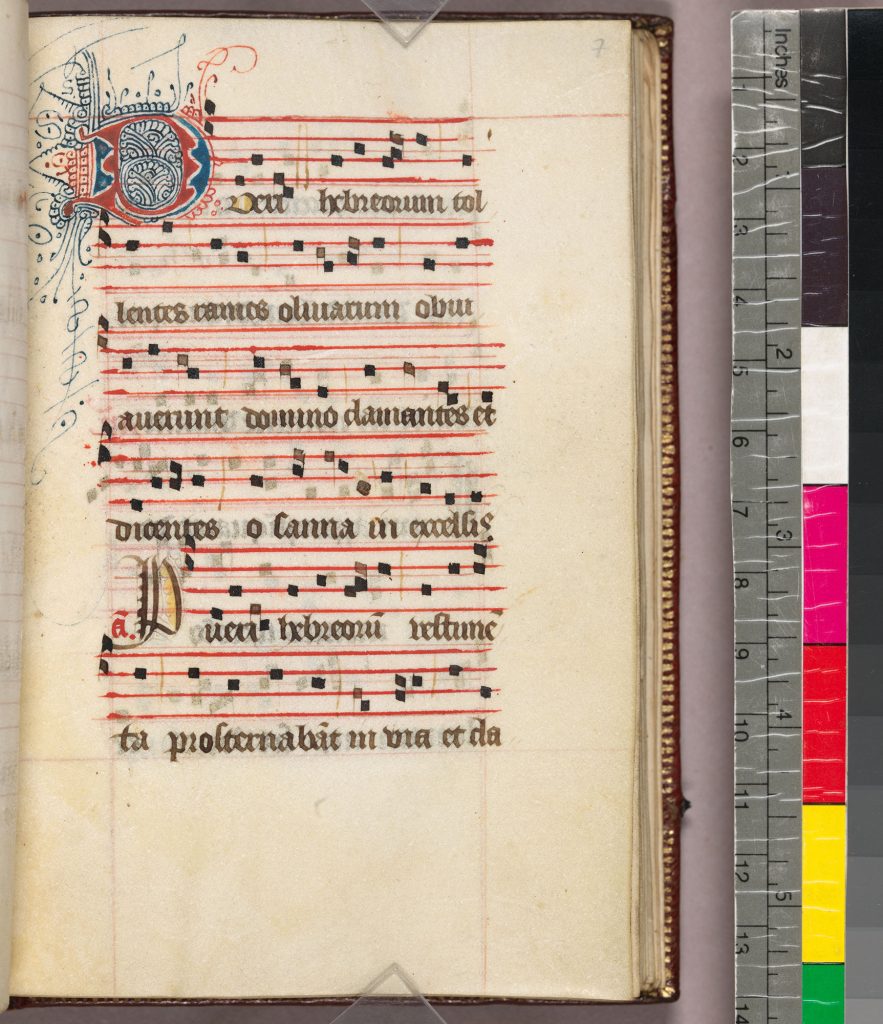

During the thirteenth century a new, more thematic type of sermon originated in the medieval universities, particularly the University of Paris: the scholastic sermon (sermo modernus). Likewise, new religious orders focused on preaching were created: namely the Franciscans in 1209 and Dominicans in 1216, who were in need of instruction and books. This resulted, especially in Paris, in an outpouring of different types of manuscripts need for sermon composition and preaching. Pandect Bibles (all biblical books in one volume) became pocket sized and portable, and a host of preaching aids were produced. For example, knowledge was systematized into reference manuals (summae) and textual anthologies (florilegia), both of which were used in composing sermons.

According to Sigfried Wenzel’s method of analysis (2015), a typical scholastic sermon can be outlined like this:

Thema is announced (quote from Scripture that the sermon builds on)

Protheme (prepares audience and capture their good will)

Oratio (prayer for divine assistance, often Hail Mary or Our Father)

Thema is repeated

Bridge passage (adapts the thema to the intention of the sermon)

Introductio thematis (why the thema was a good choice; helped by proverb, simile, quote, story)

Diuisio thematis (thema divided into parts; meaning of the thema unfolded)

Confirmatio (confirmation or proof of divisions; often with sentence from Scripture)

Prosecutio (thema developed with subdivision, subdistinction, elaboration, examples, etc.)

Vnitio (combination of all the parts)

Conclusio (closing formula with a prayer asking for God’s grace)

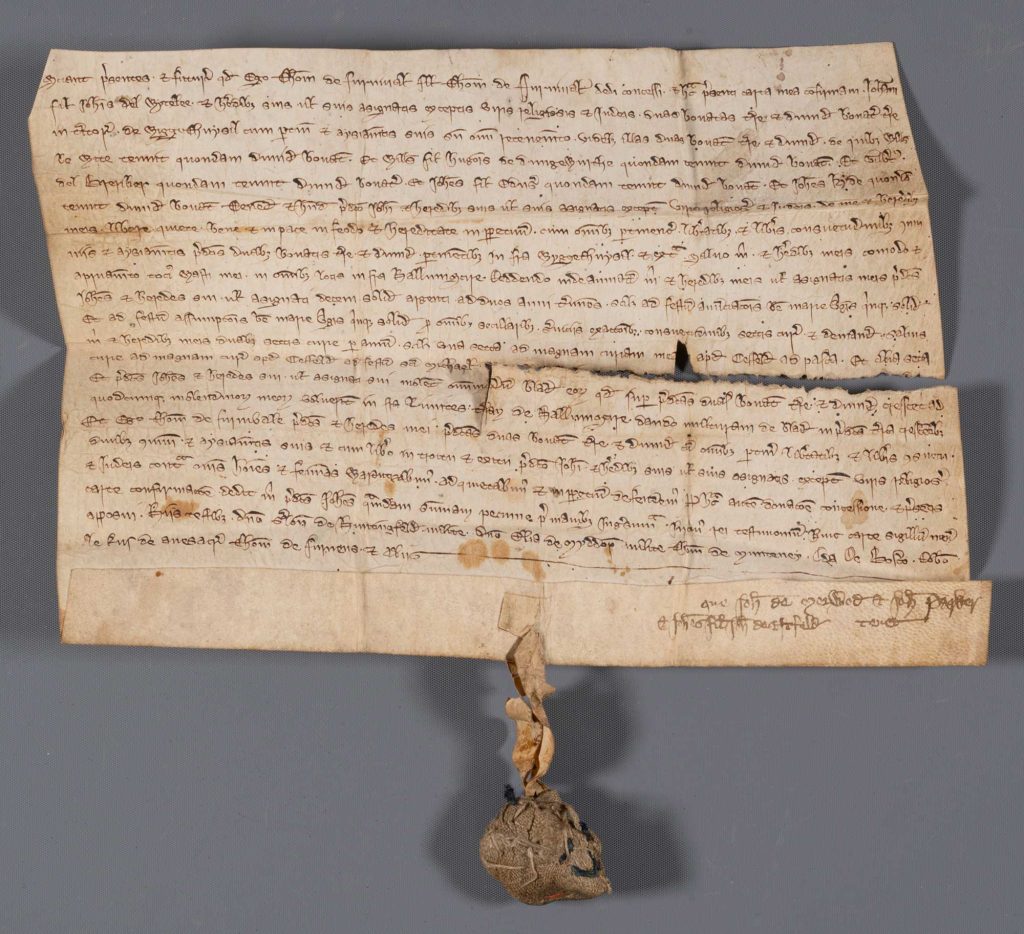

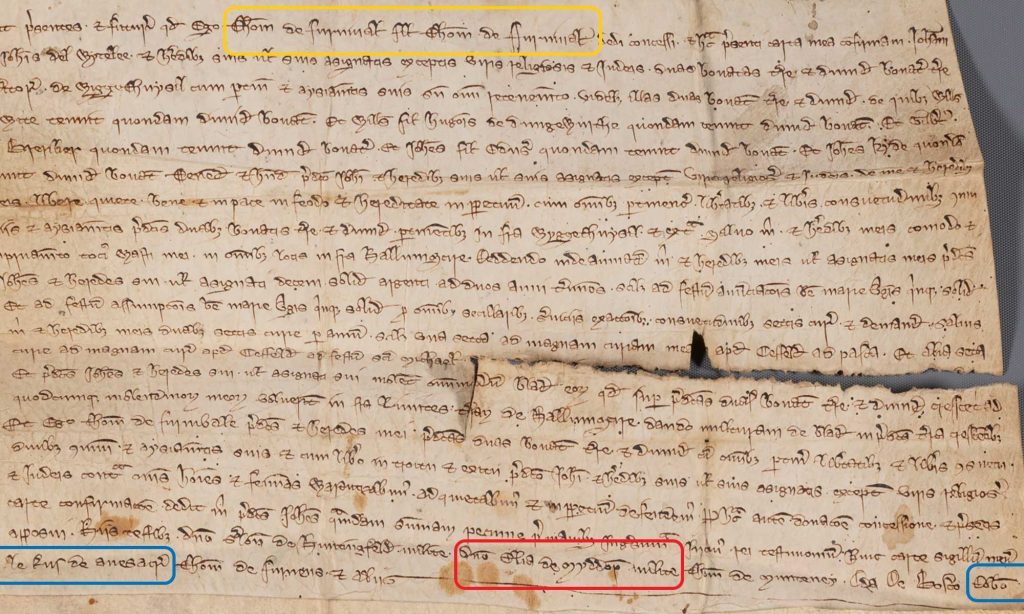

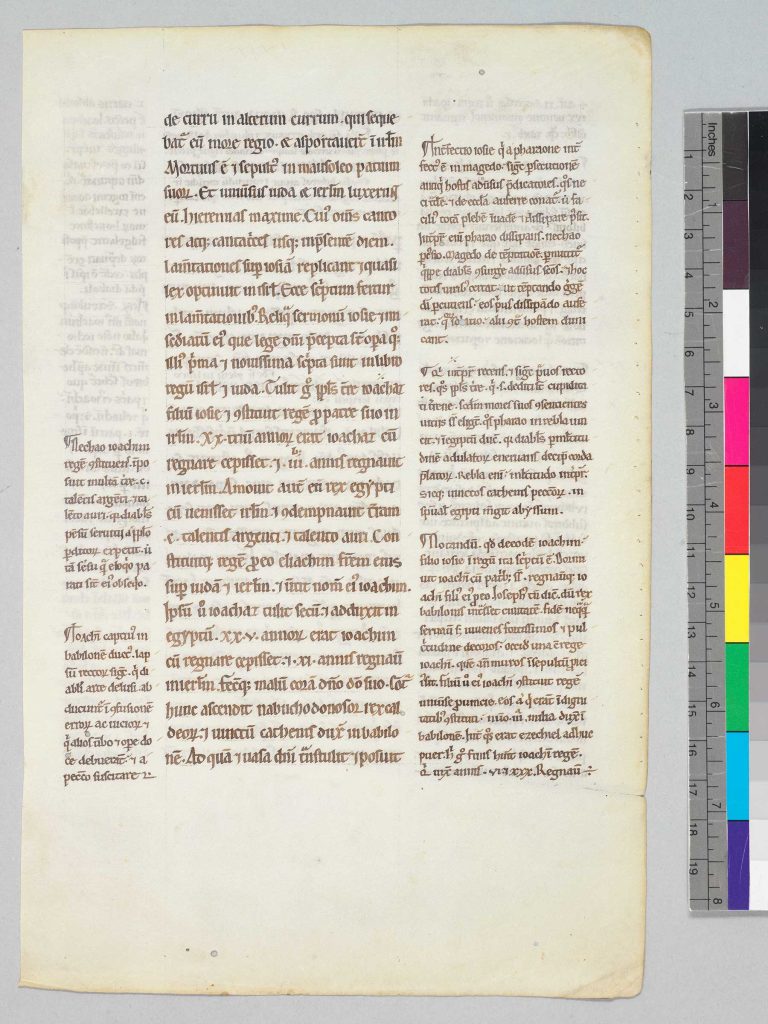

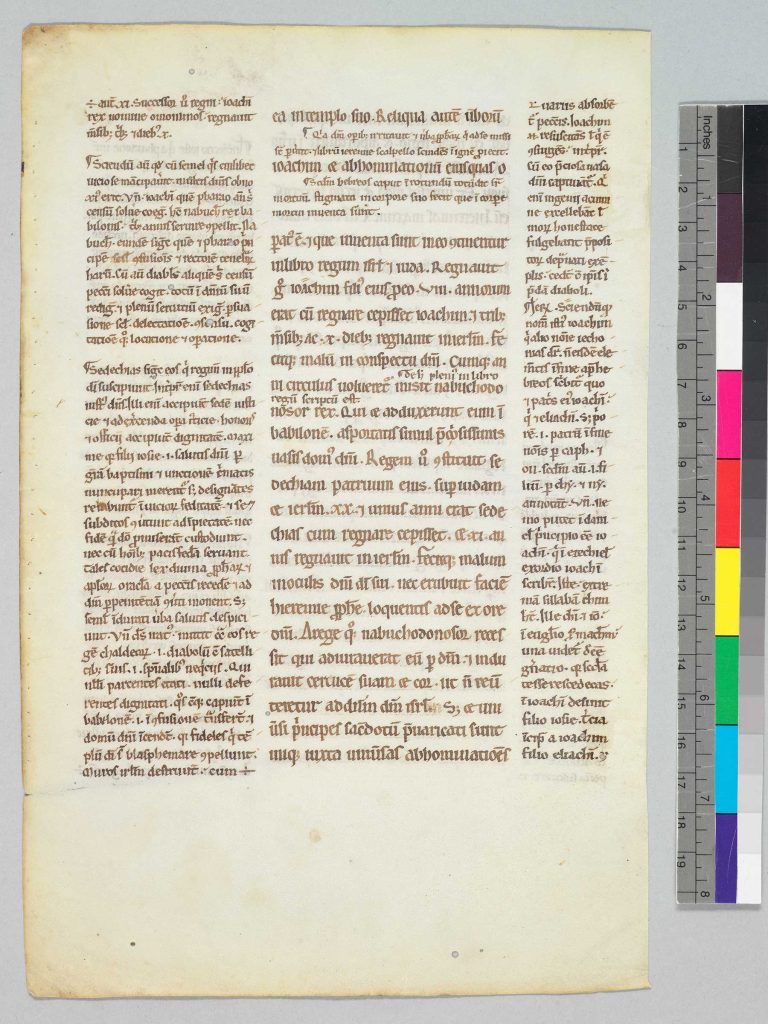

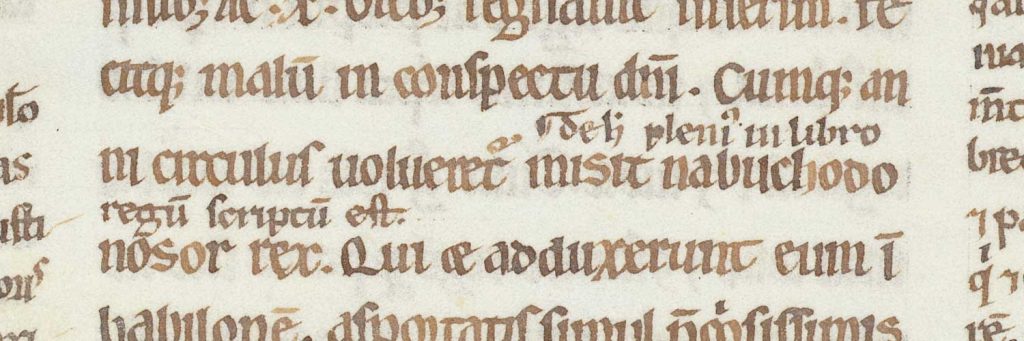

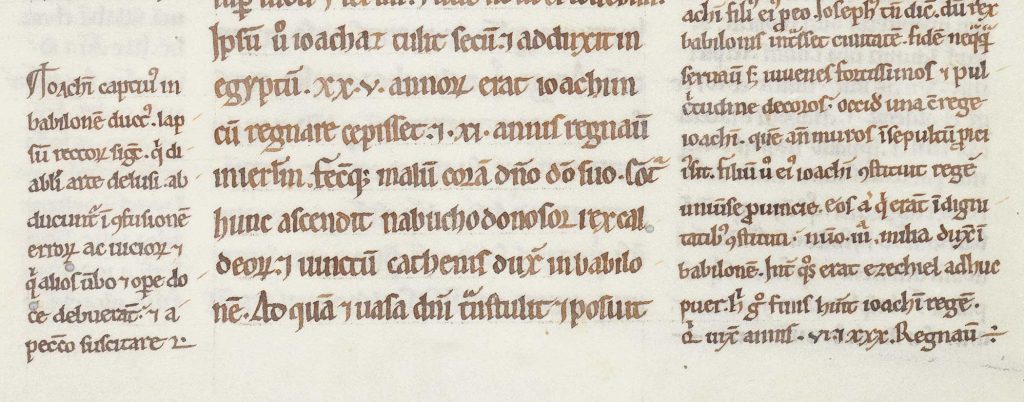

Some sermon collections enjoyed broad circulation and different traditions of use. For example, ca. 1240 Philip the Chancellor composed 330 scholastic sermons on the Psalms while he was chancellor of the Cathedral of Notre Dame in Paris. These sermons originated within the university milieu, but continued to have a robust afterlife. The fragmentary copy currently in the Hesburgh Library’s collection (cod. Lat. b. 11), once was part of the Servite Library at San Marcello al Corso in Rome ca. 1382–1402, where it was used in the formation of its novices despite being over one hundred forty years old. The Servites added an ownership inscription when the manuscript entered the collection at San Marcello. By 1402 the starving friars were selling books to survive and the library burned down in 1519. A later owner erased the inscription and obscured the medieval provenance of the manuscript, which was later dismembered in Cleveland, Ohio by biblioclast Otto F. Ege. Using ultraviolet light, the erased text can be revealed and for the first time the Servites’s ownership is known.

Bibliography

David T. Gura, A Descriptive Catalogue of the Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts of the University of Notre Dame and Saint Mary’s College, pp. 204-213. University of Notre Dame Press, 2016.

David T. Gura, “The Medieval Provenance of Otto Ege’s ‘Chain of Psalms’ (FOL 4),” Fragmentology 4 (2021): 94-99.

Sigfried Wenzel, Medieval ‘Artes Praedicandi’, pp. 48, 50-95. University of Toronto Press, 2015.