By Jennifer Brcka, Processing Archivist for Special Collections

In the immediate wake of the Anschluss, or German annexation of Austria on March 12, 1938, the German Reich initiated a campaign against that nation’s Jewish citizens. The Seklers, a Viennese family, were victims of these actions, and later, of the Holocaust. The Hildegard Sekler Collection, a recent archival acquisition by Hesburgh Libraries’ Rare Books and Special Collections, records the family’s story through a series of letters and documents.

The collection consists of over 400 pieces of correspondence generated surrounding the separation of Leopold and Toni Sekler from their daughter, Hildegard. Most relate to Hildegard’s flight from Austria at the age of sixteen, and chiefly date from the years between 1939 and 1945. The bulk are personal letters and postcards sent to Hildegard by family, friends, and her tutor. A body of official correspondence with governmental and aid agencies has been preserved here, as well. More than 100 documents and personal papers are also found within the collection. These range from official records relating to Leopold’s career in the Vienna Finance Ministry to, less formally, Hildegard’s homework assignments, school notes, and essays.

This group of personal documents includes Leopold and Toni Sekler’s passports. In August of 1938, the German authorities enacted the Executive Order on the Law on the Alteration of Family and Personal Names. This order required Jews with non-Jewish first names to formally add “Israel” for males and “Sara” for females to their legal names. The Seklers were forced to comply. Three slips noting the name changes for each remain inserted in Leopold Sekler’s Passport. Following a similar pronouncement aimed at identifying Jewish citizens, Toni Sekler’s passport was stamped with a red “J”.

Letters illuminate desperation the family felt in the months that followed. Leopold Sekler appealed to Switzerland and the United States to obtain visas for the family to emigrate. His requests were met with delays and little success. Undeterred, he sought out directories and wrote to a handful of New Yorkers, strangers with the Sekler name, whom he hoped might provide support for a visa application. Replies from a Constance Sekler express frustration over past experiences with the Consulate in Vienna, as well as with her own limited resources. Empathetic, though unable to assist, she wrote, “Whether or not we are related isn’t of great importance because I am just as much interested in your welfare in any event.” A Jack Sekler, living in the Bronx, was able to offer support, though a quota system placed the Sekler family on a waiting list, and ultimately prevented their seeking asylum in America.

In January of 1939, a letter from the Welfare Headquarters of the Jewish Cultural Society advised that it had secured passage to England for Hildegard. At age 16, she quickly fled, unaccompanied, to London where she lived in a youth hostel. A wave of letters from her parents and concerned family and friends soon followed. Many capture the bleakness of the situation for those who remained in Austria. A March 14, 1939 letter sent by Trude Mesuse states (in German), “Furthermore, your father wants you to know, if he writes “ich” like this at the end or the beginning of a sentence, you ought to pay attention to this sentence and think about it, because it will have a particular meaning he can’t express clearly writing from Vienna. And you should be careful when you write, too.”

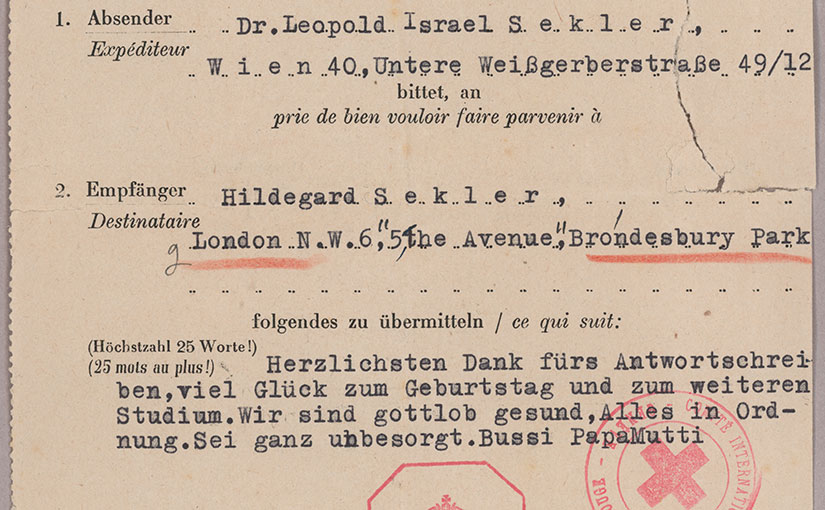

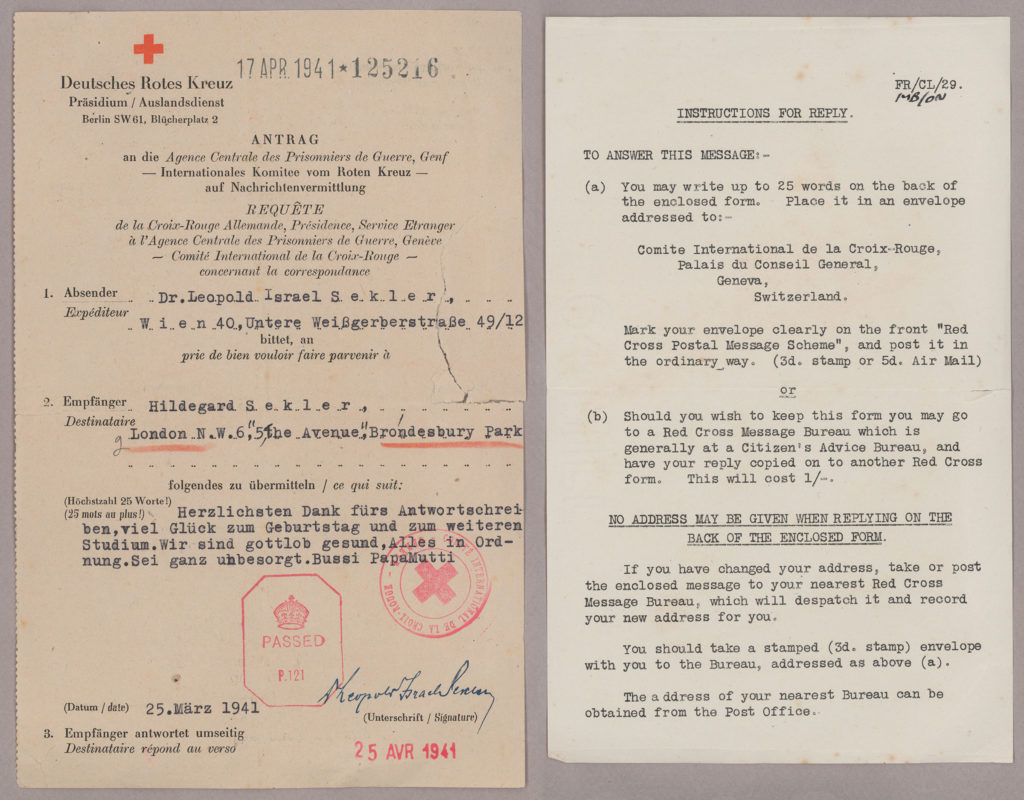

Many letters express the love and concern of parents separated from their only child. In a letter (in English) from her father on June 1, of 1940, he asks his “Dear Hilde” to, “[…] stay in the garden as long as possible and to sleep by open windows. You had better to speak only English, at home too. It would be better for all big girls. The German language you will not forget, I am sure. The conversation is the most important and the best mean to learn a language, believe me, I know it by experience.” By 1941, sending correspondence to countries at war with Germany was prohibited, and Leopold used the Red Cross Message Service to send his daughter greetings on her nineteenth birthday.

Further correspondence within the collection convey the uncertainties of life in London during the Blitz. Hildegard studied in London with a tutor, Dr. Judah Simon Goller, who wrote her frequently. In an undated letter he mentions two children, mutual acquaintances and also displaced minors, who had recently left London to be reunited with family. He muses, “So the twins have gone, and we are short two more. Please God, [may] they reach their parents in safety and soon forget all their sorrows, and remember sometimes the little joys they shared with us. I wonder what’s the good of telling me not to worry about the children when there’s a raid on? I just can’t help it.”

Hildegard continued, unsuccessfully, to seek a means for her parents to flee Austria. In October of 1942, Leopold and Toni Sekler were deported to Theresienstadt, a transit and labor camp. From there, the couple were transported to Auschwitz on October 12, 1944. Neither survived. Hildegard married her tutor, Dr. Goller, in 1960. She remained in London until her death in 2008.

Through materials largely in German or English (and occasionally in French), the Hildegard Sekler Collection presents a unique view of the Anschluss and its aftermath, unaccompanied child refugees of the Holocaust, wartime experiences in London, and personal histories of prisoners of Theresienstadt. The collection (MSE/MD 6408) is open for research in Rare Books and Special Collections, and a detailed finding aid can be found online.