While Halloween has its origins in the Western Christian feast of All Hallows (or All Saints), it has since spread to various other cultures. So too, the Special Collections holdings that relate to celebrations on or around Halloween are to be found in a variety of subject areas. This year, we bring you materials from our Latin American collections.

José Guadalupe Posada and the skull iconography of Mexico’s Dia de Muertos

by Erika Hosselkus, Curator, Latin American Collections

As many Americans prepare to celebrate Halloween on October 31, Mexico and Latino residents of the U.S. ready themselves for Dia de muertos (Day of the Dead). Celebrated between October 31 and November 2, this holiday corresponds to the Catholic All Saints’ Day (known as Todos Santos in Mexico during the colonial era and nineteenth century) and All Souls’ Day, but is uniquely Mexican in its iconographic emphasis on calaveras, or “skulls.” Candy and papier-maché skulls adorn altars prepared with offerings to the deceased (ofrendas). Toy skulls and skeletons are sold in stores. And, party-goers decorate their faces with elaborate skull makeup.

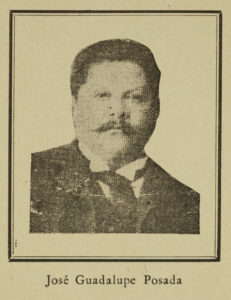

Today’s Dia de muertos skull iconography is closely associated with the work of José Guadalupe Posada (1852-1913), a Mexican lithographer, woodcut artist, engraver and etcher renowned for his satirical broadsides and flyers. During the latter half of his career, Posada worked with the printing house of Antonio Vanegas Arroyo to produce loose sheets commemorating political events, natural disasters, crimes, and festivals. Often, his original work featuring calaveras meditates on death, even if it doesn’t directly refer to Dia de muertos, as is the case with the two broadsides here, “¡Calavera Zumbona!” and “La Calavera Taurina.”

Today’s Dia de muertos skull iconography is closely associated with the work of José Guadalupe Posada (1852-1913), a Mexican lithographer, woodcut artist, engraver and etcher renowned for his satirical broadsides and flyers. During the latter half of his career, Posada worked with the printing house of Antonio Vanegas Arroyo to produce loose sheets commemorating political events, natural disasters, crimes, and festivals. Often, his original work featuring calaveras meditates on death, even if it doesn’t directly refer to Dia de muertos, as is the case with the two broadsides here, “¡Calavera Zumbona!” and “La Calavera Taurina.”

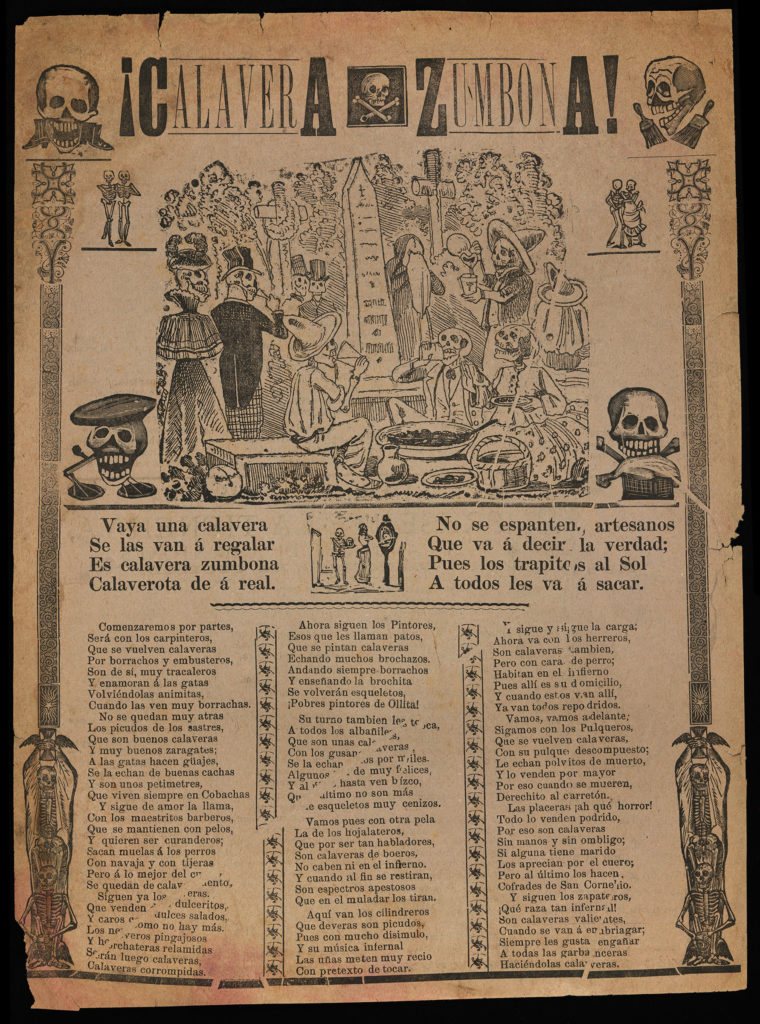

“¡Calavera Zumbona!” (“The Mocking Skull”) is a satirical piece that pokes fun at various artisan groups in Mexico City, including carpenters, tailors, candy sellers, painters, barbers, pulque sellers and more while also pointing to the universality of mortality and death. Carpenters are described as drunkards while tinsmiths are overly-loquacious. Practitioners of all crafts wind up, in the image created by Posada, as skulls in a cemetery in the end. The offerings of food and the small, round “pan de muertos” bread roll in the lower left-hand corner of the image are both traditional of Dia de muertos.

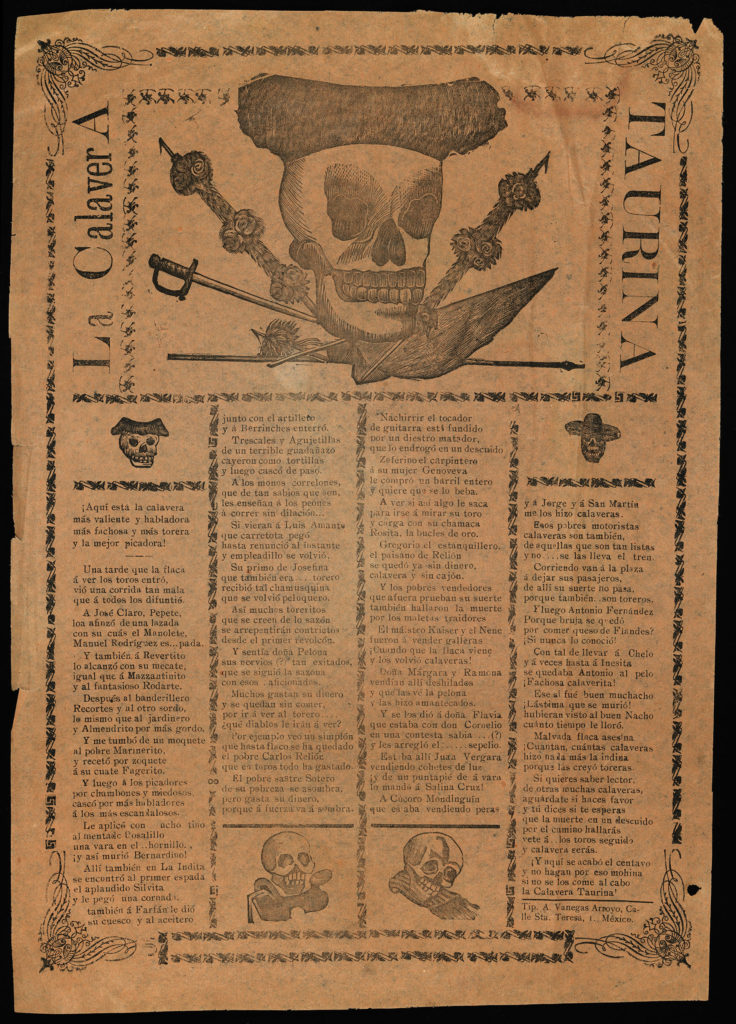

“La Calavera Taurina” is an homage to deceased bullfighters, who had been eaten or consumed by the “taurine skull” of death.

Both of these prints are on very thin paper. “¡Calavera Zumbona!” is an imperfect print with lines striking out parts of the text and main image. These elements attest to affordability of the materials used by the Vanegas shop and to the rapidity with which broadsides were printed.

Posada was rediscovered by Mexican Revolution-era muralists not long after his death in 1913. Among them, Jean Charlot was among the first to highlight Posada’s calaveras. In 1947, he worked with the still-operating Vanegas Arroyo printhouse to issue 450 copies of a bilingual portfolio entitled 100 Grabados en madera por Posada (100 Woodcuts by Posada). Here, Charlot reproduces the smaller and lesser-know woodcuts produced by Posada. Many feature calaveras accompanied by verse. One (#12) even commemorates Todos Santos (All Saints Day / All Saints’ Eve / All Hallow’s Eve) by name.

Posada was rediscovered by Mexican Revolution-era muralists not long after his death in 1913. Among them, Jean Charlot was among the first to highlight Posada’s calaveras. In 1947, he worked with the still-operating Vanegas Arroyo printhouse to issue 450 copies of a bilingual portfolio entitled 100 Grabados en madera por Posada (100 Woodcuts by Posada). Here, Charlot reproduces the smaller and lesser-know woodcuts produced by Posada. Many feature calaveras accompanied by verse. One (#12) even commemorates Todos Santos (All Saints Day / All Saints’ Eve / All Hallow’s Eve) by name.

Charlot translates the verse as follows:

12. All Hallow’s Eve.

At last the day of all the dead

has arrived.

On which they rejoice, replete

with pleasures without

number.

In place of sad mourning for ourselves,

Let us, with laughs and pulque,

go cry in our cups.

Lo que nos dice esta frase :

Que sólo el ser que no nace

No puede ser calavera.

Son muy traidoras, deveras.

– Pues, a mí, las calaveras,

Nomás me pelan los dientes…

Y a toditos nos agarra,

Hay que suerte tan chaparra,

Pues creo que ni madre tiene.

Happy Halloween to you and yours

from all of us in Notre Dame’s Special Collections!

Halloween 2016 RBSC post: Ghosts in the Stacks

Halloween 2017 RBSC post: A spooky story for Halloween: The Goblin Spider

Halloween 2018 RBSC post: A story for Halloween: “Johnson and Emily; or, The Faithful Ghost”